![]()

1 Understanding Learning Disability

INTRODUCTION

This book is designed to provide a framework of good practice guidance to support health care professionals working in general hospital services to provide care to people with a learning disability. This first chapter provides an introduction to the nature of learning disability and insight into what this means for the person. It explores how to establish if your patient has a learning disability, and the perceptions and attitudes of health care professionals towards people with a learning disability. The chapter then continues to summarise what the current evidence base says about how to identify and meet the health needs of people with a learning disability, including factors and barriers that influence the health care process and how to overcome these. The needs of families and carers are highlighted and the important role they have to play in the process. The chapter concludes with an introduction to the person-centred approaches that are a central aspect of learning disability practice.

We do not always know who is disabled. Many people associate disability with wheelchair use, yet less than 5% of disabled people use a wheelchair. Anyone who meets the following definition from the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) (Department of Health 1995b) is considered to be disabled:

Someone with a physical or mental impairment which has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on their ability to carry out normal day to day activities.

This includes physical impairments to senses such as sight and hearing, and mental impairments such as learning disabilities and mental illness. Conditions covered may include things such as severe depression, diabetes, dyslexia, epilepsy and arthritis.

Substantial includes:

- Inability to see moving traffic clearly enough to cross a road safely

- Inability to turn taps or knobs

- Inability to remember and relay a simple message correctly

Long-term means that the effects have lasted, or are expected to last 12 months or more.

Day-to-day activities include mobility, manual dexterity, physical coordination, continence, ability to lift, speech, hearing, eyesight, memory and recognising physical danger.

Considering the Disability Discrimination Act definition of disability, it is clear that a wide range of people and health conditions could be incorporated within this.

The new Equality Act 2010 will come into force in October 2010. The Act brings disability, sex, race and other grounds of discrimination within one piece of legislation, and also makes changes to the law. Further information about the Act can be found at: http://www.equalities.gov.uk/equality_act_2010.aspx

DEFINITIONS AND CAUSES OF A LEARNING DISABILITY

Definitions

A learning disability is a lifelong condition, which has its beginning before, during or after birth, or as a result of injury to the brain before the age of 18, which affects an individual's ability to learn, communicate or do everyday things. A learning disability is not an illness, and whilst the condition cannot be ‘cured’, it is possible for an individual with a learning disability to develop new skills and progress.

A learning disability should not be confused with educational ‘learning difficulties’ such as dyslexia, and hyperactive disorders, or mental illness, which are other conditions, not covered within this book. People who acquire brain injuries after the age of 18 are not normally considered to have a learning disability, as the injury has occurred after the brain was fully developed.

Mackenzie (2005), cited in Grant et al. (2005, p. 49), explains that ‘the international Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders (ICD-10) (World Health Organisation 1992) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Association 1994) are the main classification systems currently in use’. ICD is the system used in the UK. Both these systems use the term ‘mental retardation’ and this equates to learning disability. Whilst the term ‘mental retardation’ may be defined in the ICD, it is however unacceptable for use in clinical practice.

Mackenzie outlines the following (broadly similar) ICD and DSM definitions of learning disability:

DSM-IV definition

1. Significantly subaverage intellectual functioning: an intelligence quotient (IQ) of approximately 70 or below on an individually administered IQ test (for infants, a clinical judgement of significantly subaverage intellectual functioning).

2. Concurrent deficits or impairments in present adaptive functioning (i.e. the person's effectiveness in meeting the standards expected for his or her age by his or her cultural group) in at least two of the following areas: communication, self-care, home living, social/interpersonal skills, use of community resources, self-direction, functional academic skills, work, leisure, health and safety.

3. The onset is before 18 years of age.

ICD-10 definition

Mental retardation is a condition of arrested or incomplete development of mind, which is characterised by impairment of skills manifested during the developmental period, which contribute to the overall level of intelligence, i.e. cognitive, language, motor and social abilities.

Mackenzie also explains that ‘each is based on the presence of impairments in adaptive function in association with low intelligence quotient (IQ)’.

You may have heard of a variety of different terms used to describe someone with a learning disability, many of them are now considered to be inappropriate, and some are actually offensive and should never be used.

Reflective Learning Point:

Think about all the terms you may have heard to define a learning disability and how they would sound to a person with a learning disability and their family.

Mackenzie (2005), cited in Grant et al. (2005), continues to describe the following World Health Organisation (1980) definitions:

- Impairment – Any loss or abnormality of physical or psychological function

- Disability – Interference with activities of the whole person (usually described in learning disability practice as activities of daily living)

- Handicap – The social disadvantage to an individual as a result of impairment or a disability

The Mental Health Act (Department of Health 1983) uses the term ‘mental impairment’, and the term ‘mental handicap’ may still be used, though this is not considered acceptable any more. All these terms can be seen to represent what people may consider as features of a disability. A social model of disability, as opposed to a medical model, identifies attitudes and environment as being major causes of disability, and not the personal abilities of the people involved. The medical model focuses on the clinical aspects of the condition and how it is treated, and not necessarily the impact on the person.

The Department of Health (2001a) report ‘Valuing People’ defines a learning disability as having the following characteristics:

- A significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information, to learn new skills (impairment of intelligence)

- A reduced ability to cope independently (impaired social functioning)

- Started before adulthood (usually considered to be age 18), with a lasting effect on development

Each individual goes through a comprehensive process of assessment before a diagnosis of learning disability can be confirmed. A syndrome is the medical term for a recognised set of clinical features which commonly occur together. Some syndromes (e.g. Down's syndrome) are named after the person who first described them or others after a particular feature of the syndrome.

Mackenzie (2005) (cited in Grant et al. 2005, p. 49) outlines that ‘the term “special needs” refers to children who have been given a Statement of special educational needs by their local education authority. The educational category of severe learning difficulties corresponds more closely with learning disabilities as used in health settings’.

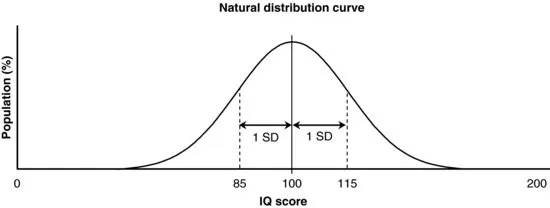

Intelligence is formally measured through a cognitive assessment by a qualified clinical psychologist, who gives people an IQ score. The Royal College of Nursing (2006) explains how IQ range is naturally distributed in the population and the average IQ (mean score) is 100, with a standard deviation range of 15 points on either side. Therefore, anyone with an IQ score between 85 and 115 is said to be of average intelligence (Fig. 1.1).

The range of 1 standard deviation above or below the mean represents 68% of the population. Another 28% of the population has an IQ score within 2 standard deviations of the mean (14% above and 14% below), leaving a small number of individuals (2%) at either end of the scale outside of 2 standard deviations of the mean.

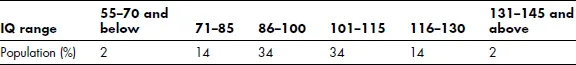

The range of IQ distribution in the population is illustrated in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 The range of IQ distribution in the population

From this table we can see that approximately 2% of the population can be considered to have a learning disability.

Impairment of intelligence can be presented at different levels and the British Psychological Society (2000) explains that:

- People with an IQ of 55–69 can be said to have a significant impairment in intellectual functioning.

- People with an IQ of below 55 can be said to have a severe impairment in intellectual functioning.

IQ tests are not routinely carried out for all people with a learning disability, so this information may not be available for the people that you see. A referral can be made when a need to measure intelligence is identified, for example when capacity to consent issues arises.

The term ‘mild learning disability’ may be used to describe a significant impairment, and the terms ‘moderate, severe or profound’ may be used to describe a severe impairment in intellectual functioning. The term ‘intellectual disability’ is commonly used in other countries. Some people with an IQ in the range 70–85 can find that their learning impairment is often not diagnosed at an early age, and they are not able to access services designed for people with significant or severe impairments.

Prevalence

Mencap (2002) reported, ‘There are about 1.5 million people with a mild or moderate learning disability, and an estimated 210,000 individuals with severe or profound and multiple learning disabilities currently living in the United Kingdom’.

Michaels (2008, p. 14) reported that ‘estimates of the prevalence of learning disability vary reflecting differences in definition. Department of Health figures...