![]()

CHAPTER 1

What Is Nonprofit Strategy?

Nonprofits differ from their counterparts in the for-profit world, and these differences must be made clear as they set out to create strategy. While for-profit organizations are primarily concerned with producing profits and beating their competition, nonprofits are primarily concerned with accomplishing their missions—making a difference for society. Therefore the objective of nonprofit strategy is to guide the organization on the way to mission accomplishment.

WHAT IS STRATEGY?

The concept of strategy is often misunderstood in all sectors—corporate, government, and nonprofit. Hence the plethora of strategy consultants and books (here’s another) abound. So let’s begin by simplifying.

Strategy is an integrated and coherent explanation of how an organization is going to guide its performance in the future. It explains how its essential operations will interact with one another, and within the organization’s environment, to produce effective performance.

We’ll now look at the different parts of this definition.

An Integrated Explanation of Performance

Many authors point out that the historic roots of strategy come from the military. For example, “The term strategic is derived from the Greek strategos, meaning ‘a general set of maneuvers carried out to overcome an enemy during combat”’ (Nutt & Backoff, 1992, p. 56). Using the same military mind-set, Hambrick & Fredrickson (2005) call strategy “the art of the general” and explain that “Great generals think about the whole. They have a strategy; it has pieces, or elements, but they form a coherent whole. Business generals . . . must also have a strategy—a central, integrated, externally oriented concept of how the business will achieve its objectives” (p. 52). Others build on this militaristic concept to describe strategy more generally for organizations as “determining what an organization intends to be in the future and how it will get there” (Barry, 1986, p. 10).

When many organizations discuss their strategy, they end up listing pieces or elements without an explanation of how these are integrated into a whole. For example, organizations will list goals, initiatives, and/or plans without an explanation of how these are connected to one another. In fact, any connection between these various elements is often unclear. It’s not that goals and initiatives and plans are bad, it is just that without an explanation of how they fit and interact together to move the organization forward, they do not constitute a strategy.

Explaining a strategy is like telling a story that has a beginning, middle, and end. As we think back to the example of generals, we can imagine them talking with their troops to explain what they are about to do: “First, we are going to . . . then some of you will . . . which will then allow others of us to . . . and that will give us the opening to . . . which will lead us on to victory.” Note how the actions in this simple example are connected with one another. Many people refer to strategy as a cause-and-effect story that describes the journey from the present to the desired future. Certain actions create certain effects, which then allow new actions to be taken, and so on. The strategy story becomes the guiding narrative for the organization’s future activities.

In order for a strategy to work well, the various strategic actions taken need to have positive interactions. They need to produce a positive reinforcing cyclical effect upon one another so that the collective result of the actions propels the organization into the future. We know that organizations can find themselves in vicious downward spirals. Good strategy creates a virtuous positive spiral toward high performance (Senge, 1990).

The importance of these positive interactions is central to the concept of systems thinking. Systems thinking seeks to understand an organization as a whole. It looks at how the different parts of the organization interact and affect one another. Rather than analyzing each part of the organization separately, the parts are looked at synthetically. Russell L. Ackoff, one of the leaders of the systems thinking approach, describes one of the tenets of this approach: “A system’s performance is the product of the interactions of its parts” (1999, p. 33) rather than the sum of the performance of the parts or “how they act taken separately” (1999, p. 9).

Crafting strategy, this cause-and-effect story, is a creative act, not an analytical function. It is a process of considering the organization’s current situation, such as its SWOTs (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats), looking at the organization’s desired future, and designing a set of actions which will catapult it forward. Typically, an organization will want to leverage strengths, seize opportunities, fortify weaknesses, and block threats. These orchestrated actions all make up the cause-and-effect story. In this sense, there is no such thing as a right or wrong strategy and a strategy cannot be figured out. It needs to be generated from the strategist’s understanding of the current situation and commitment to pursuing the organization’s future intentions. This is what Henry Mintzberg refers to as “strategic thinking” as he compares it to the analytical function of “strategic planning”: “Strategic thinking, in contrast, is about synthesis. It involves intuition and creativity. The outcome of strategic thinking is an integrated perspective of the enterprise, a not-too-precisely articulated vision of direction . . . ” (1994, p. 108).

While a strategy may not necessarily be right or wrong, it can be sufficient or deficient. If the strategy does not coherently explain how the various strategic actions it is going to take are integrated with one another and/ or does not explain how these actions will work together to create a virtuous cycle of performance, then it will serve as little future guidance to the organization.

In order to further understand the essential elements of the strategy story, it is helpful first to understand the essential elements of the means of organization performance.

Essential Elements of Performance

Many different aspects of an organization need to work together well in order for it to achieve high performance. This is true regardless of the type of organization it is—for-profit, government, or nonprofit. The strategy definition we are working from states that strategy explains how its essential operations will interact with one another, and within the organization’s environment, to produce effective performance. The “essential operations” of an organization are its primary means of performance.

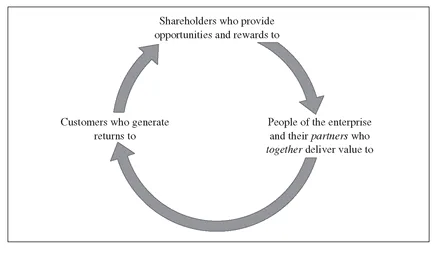

In his book Make Success Measurable! (1999), organization expert Doug Smith outlines the essential elements of an organization’s operations, which it needs to integrate in order to be successful. These activities are essential for organizations from all three sectors. The categories of activities can be thought of as financing, staffing, and provision of products/services/ programs of value.

These categories of activities will make intuitive sense to most people who are familiar with running an organization. The categories cover essential questions:

1. What products/services/programs of value are we going to provide and to whom?

2. Who do we need to hire to provide the products/services/ programs?

3. How do we finance all of this activity?

The specific ways the activities are carried out will vary within different sectors, but answering these questions is essential to each. Smith explains that organizations must create a “reinforcing cycle” of actions that connects the three categories of activity so that they build upon one another to create a “cycle of sustainable performance.”

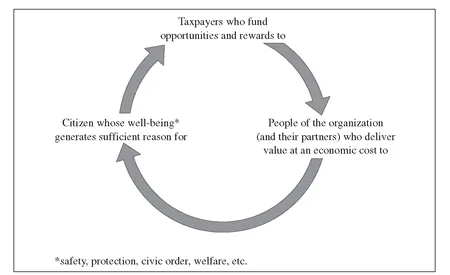

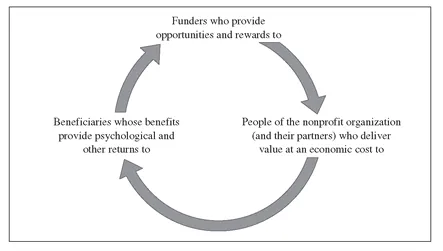

For the for-profit entity, the cycle includes shareholders who provide opportunities and rewards to people of the enterprise and their partners who provide value to customers who generate returns to shareholders . . . and the cycle continues (see Figure 1.1). Each of the three parts of the cycle benefits from the other two and contributes to them as well. Smith then changes the terminology slightly to demonstrate how the same logic works for government and nonprofit organizations. In government, shareholders are taxpayers, while in nonprofits they are funders. In each case, though, the function is about financing the operation. Customers become citizens in the government model and beneficiaries in the nonprofit model. In this case, it is all about providing products/services/programs of value regardless of the sector (see Figures 1.2 and 1.3).

FIGURE 1.1 Cycle of Sustainable Performance (a)

Source: Douglas Smith, Make Success Measurable! (1999). Reprinted with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 1.2 Cycle of Sustainable Performance (b)

Source: Douglas Smith, Make Success Measurable! (1999). Reprinted with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 1.3 Cycle of Sustainable Performance (c)

Source: Douglas Smith, Make Success Measurable! (1999). Reprinted with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

For each sector, the same cause-and-effect logic applies to the explanation of how strategic actions in one area of the organization’s operations will impact the others. Smith calls this logic a “performance story,” and he points out the “cyclical interdependence” that each area has on the others.

Consider some examples of this cyclical interdependence in the nonprofit world:

• If not properly financed, then a nonprofit will not be able to retain the quality or quantity of staff it needs. Therefore, it needs to figure out how to be well financed.

• If the appropriate quantity and quality of staff (and/or volunteers) are not attracted and retained, then it will not be able to provide programs and services well. Therefore, it needs to figure out how to attract and retain staff and/or volunteers.

• If programs and services are not provided well, then funders (which can include those paying fees for service) will not renew their support. Therefore, it needs to figure out how to provide programs and services well.

Without all three of these areas of activities working well and positively feeding off of one another, the cyclical interdependence breaks down and performance is not optimized.

So as organizations answer the three questions posed at the outset of this section, they need to be sure that their plans in each category positively interact with their plans in the other categories. Since the answers to these questions are essential to the organization’s performance, they are also essential to the organization’s strategy and need to be included in the organization’s strategy story.

The three essential elements of staffing, financing, and products/ services/programs are the “means” of performance, and they need to be addressed by organizations in all three sectors. However, an important way that the for-profit, government, and nonprofit sectors differ is by their core purpose—why they exist. Therefore, while they have similar categories of means of production and performance, their ends are quite different—and this will impact how they craft strategy.

STRATEGY GUIDES PERFORMANCE

The purpose of having a strategy is to guide the organization toward its desired future. In other words, the strategy guides the organization’s performance. With this in mind, we can examine the different ways in which for-profit and nonprofit organizations think about performance and then look at implications for strategy.

For a number of decades, consultants and authors have taken the general idea of strategy—built upon its militaristic past—to design methods for corporate organizations to craft and implement strategy. In more recent years, nonprofit organizations have begun seeing the value of strategic planning. They have attempted to take methodologies used in the for-profit world and apply them to nonprofits.

The results of these efforts have been mixed. The difficulty in translating for-profit methods of strategy development into the nonprofit world was one of the motivating forces behind a research forum sponsored at Harvard in 1998. From their work with nonprofit practitioners, the conveners stated, “The feedback from these practitioners was that strategy models developed for for-profit organizations were relevant for their purposes, but these models required significant modification or adjustment to work in nonprofit settings” (Backman, Grossman, & Rangan, 2000, p. 2).

While numerous books and articles on nonprofit strategy have been produced since this conference was held more than 10 years ago, nonprofit executives still find difficulty in applying for-profit methods to their unique situations. The development of modifications and adjustments that need to be made in for-profit methodologies of strategy development, in order for them to work for nonprofits, begins by examining the key differences between the two types of organizations—their reasons for being and their notions of performance.

For-Profit Performance

For-profit organizations typically judge their performance by various perspectives on how much profit they make. They have investors who expect a return on that investment. Many companies will also monitor metrics such as customer and/or employee satisfaction, but most do this as a means to the important end of making profit. Some companies may take a shorter-term view of profits (e.g., most companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange) while some may focus on the longer term (e.g., Berkshire Hathaway). Some may look at different permutations of profit, such as price of traded shares or return on invested capital. But, essentially, the idea is to make a profit.

Certainly, many for-profit entities are also concerned about the “social value” they produce for society and they are increasingly concerned about their impact on other various stakeholders. However, for most, these are secondary to their interest in making a profit and returning value to shareholders. A statement from the Business Roundtable, an association of CEOs of leading U.S. companies, reinforces this in its 2005 version of its Principles of Corporate Governance:

Corporations are often said to have obligations to shareholders and other constituencies, including employees, the communities in which they do business and government, but these obligations are best viewed as part of the paramount duty to optimize long-term shareholder value. (2005, p. 31)

This statement is not as blunt as renowned economist Milton Friedman’s famous article “The Social Responsibility of the Corporation is to Increase its Profits” (1970), but it makes the same point.

The definition we are working from states that strategy explains how its essential operations will interact with one another, and within the organization’s environment, to produce effective performance. We see that effective performance means making profit for the for-profi...