This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Introduction to Search Engines and Web Navigation

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book is a second edition, updated and expanded toexplain the technologies that help us find information on the web. Search engines and web navigation tools have become ubiquitous in our day to day use of the web as an information source, a tool for commercial transactions and a social computing tool. Moreover, through the mobile web we have access to the web's services when we are on the move. This book demystifies the tools that we use when interacting with the web, and gives the reader a detailed overview of where we are and where we are going in terms of search engine and web navigation technologies.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access An Introduction to Search Engines and Web Navigation by Mark Levene in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Web Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

“People keep asking me what I think of it now it's done. Hence my protest: The Web is not done!”

Tim Berners-Lee, Inventor of the World Wide Web

The last two decades have seen dramatic revolutions in information technology; not only in computing power, such as processor speed, memory size, and innovative interfaces, but also in the everyday use of computers. In the late 1970s and during the 1980s, we had the revolution of the personal computer (PC), which brought the computer into the home, the classroom, and the office. The PC then evolved into the desktop, the laptop, and the netbook as we know them today.

The 1990s was the decade of the World Wide Web (the Web), built over the physical infrastructure of the Internet, radically changing the availability of information and making possible the rapid dissemination of digital information across the globe. While the Internet is a physical network, connecting millions of computers together globally, the Web is a virtual global network linking together a massive amount of information. Search engines now index many billions of web pages and that number is just a fraction of the totality of information we can access on the Web, much of it residing in searchable databases not directly accessible to search engines.

Now, in the twenty-first century we are in the midst of a third wave of novel technologies, that of mobile and wearable computing devices, where computing devices have already become small enough so that we can carry them around with us at all times, and they also have the ability to interact with other computing devices, some of which are embedded in the environment. While the Web is mainly an informational and transactional tool, mobile devices add the dimension of being a location-aware ubiquitous social communication tool.

Coping with, organizing, visualizing, and acting upon the massive amount of information with which we are confronted when connected to the Web are amongst the main problems of web interaction (1). Searching and navigating (or surfing) the Web are the methods we employ to help us find information on the web, using search engines and navigation tools that are either built-in or plugged-in to the browser or are provided by web sites.

In this book, we explore search and navigation technologies to their full, present the State-of-the art tools, and explain how they work. We also look at ways of modeling different aspects of the Web that can help us understand how the Web is evolving and how it is being and can be used. The potential of many of the technologies we introduce has not yet been fully realized, and many new ideas to improve the ways in which we interact with the Web will inevitably appear in this dynamic and exciting space.

1.1 Brief Summary of Chapters

This book is roughly divided into three parts. The first part (Chapters 1–3) introduces the problems of web interaction dealt with in the book, the second part (Chapters 4–6) deals with web search engines, and the third part (Chapters 7–9) looks at web navigation, the mobile web, and social network technologies in the context of search and navigation. Finally, in Chapter 10, we look ahead at the future prospects of search and navigation on the Web.

Chapters 1–3 introduce the reader to the problems of search and navigation and provide background material on the Web and its users. In particular, in the remaining part of Chapter 1, we give brief histories of hypertext and the Web, and of search engines. In Chapter 2, we look at some statistics regarding the Web, investigate its structure, and discuss the problems of information seeking and web search. In Chapter 3, we introduce the navigation problem, discuss the potential of machine learning to improve search and navigation tools, and propose Markov chains as a model for user navigation.

Chapters 4–6 cover the architectural and technical aspects of search engines. In particular, in Chapter 4, we discuss the search engine wars, look at some usage statistics of search engines, and introduce the architecture of a search engine, including the details of how the Web is crawled. In Chapter 5, we dissect a search engine's ranking algorithm, including content relevance, link- and popularity-based metrics, and different ways of evaluating search engines. In Chapter 6, we look at different types of search engines, namely, web directories, search engine advertising, metasearch engines, personalization of search, question answering engines, and image search and special purpose engines.

Chapters 7–9 concentrate on web navigation, and looks beyond at the mobile web and at how viewing the Web in social network terms is having a major impact on search and navigation technologies. In particular, in Chapter 7, we discuss a range of navigation tools and metrics, introduce web data mining and the Best Trail algorithm, discuss some visualization techniques to assist navigation, and look at the issues present in real-world navigation. In Chapter 8, we introduce the mobile web in the context of mobile computing, look at the delivery of mobile web services, discuss interfaces to mobile devices, and present the problems of search and navigation in a mobile context. In Chapter 9, we introduce social networks in the context of the Web, look at social network analysis, introduce peer-to-peer networks, look at the technology of collaborative filtering, introduce weblogs as a medium for personal journalism on the Web, look at the ubiquity of power-law distributions on the Web, present effective searching strategies in social networks, introduce opinion mining as a way of obtaining knowledge about users opinions and sentiments, and look at Web 2.0 and collective intelligence that have generated a lot of hype and inspired many start-ups in recent years.

1.2 Brief History of Hypertext and the WEB

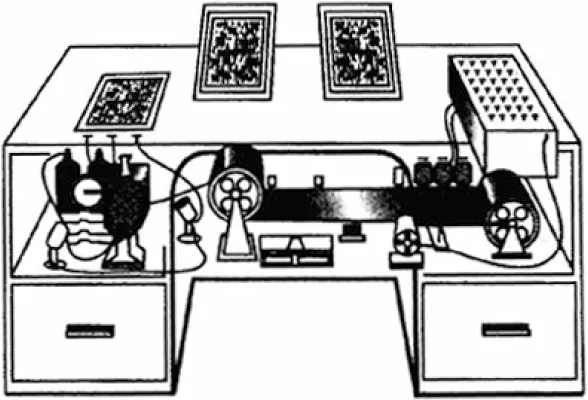

The history of the Web dates back to 1945 when Vannevar Bush, then an advisor to President Truman, wrote his visionary article “As We May Think,” and described his imaginary desktop machine called memex, which provides personal access to all the information we may need (2). An artist's impression of memex is shown in Fig. 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Bush's memex. (Source: Life Magazine 1945;9(11):123.)

The memex is a “sort of mechanized private file and library,” which supports “associative indexing” and allows navigation whereby “any item may be caused at will to select immediately and automatically another.” Bush emphasizes that “the process of tying two items together is an important thing.” By repeating this process of creating links, we can form a trail which can be traversed by the user; in Bush's words, “when numerous items have been thus joined together to form a trail they can be reviewed in turn.” The motivation for the memex's support of trails as first-class objects was that the human mind “operates by association” and “in accordance to some intricate web of trails carried out by the cells of the brain.”

Bush also envisaged the “new profession of trailblazers” who create trails for other memex users, thus enabling sharing and exchange of knowledge. The memex was designed as a personal desktop machine, where information is stored locally on the machine. Trigg (3) emphasizes that Bush views the activities of creating a new trail and following a trail as being connected. Trails can be authored by trailblazers based on their experience and can also be created by memex, which records all user navigation sessions. In his later writings on the memex, published in Ref. 4, Bush revisited and extended the memex concept. In particular, he envisaged that memex could “learn from its own experience” and “refine its trails.” By this, Bush means that memex collects statistics on the trails that the user follows and “notices” the ones that are most frequently followed. Oren (5) calls this extended version adaptive memex, stressing that adaptation means that trails can be constructed dynamically and given semantic justification; for example, by giving these new trails meaningful names.

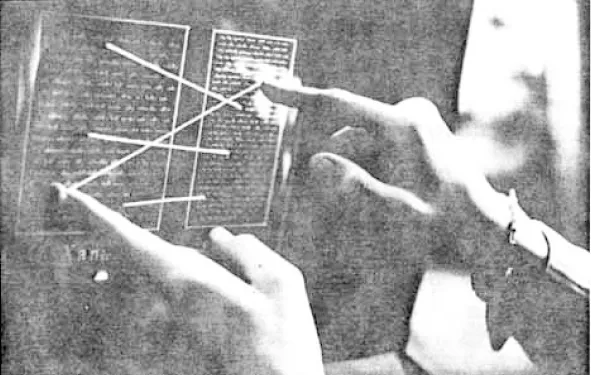

The term hypertext (6) was coined by Ted Nelson in 1965 (7), who considers “a literature” (such as the scientific literature) to be a system of interconnected writings. The process of referring to other connected writings, when reading an article or a document, is that of following links. Nelson's vision is that of creating a repository of all the documents that have ever been written thus achieving a universal hypertext. Nelson views his hypertext system, which he calls Xanadu, as a network of distributed documents that should be allowed to grow without any size limit, such that users, each corresponding to a node in the network, may link their documents to any other documents in the network. Xanadu can be viewed as a generalized memex system, which is both for private and public use. As with memex, Xanadu remained a vision that was not fully implemented; a mockup of Xanadu's linking mechanism is shown in Fig. 1.2. Nelson's pioneering work in hypertext is materialized to a large degree in the Web, since he also views his system as a means of publishing material by making it universally available to a wide network of interconnected users.

Figure 1.2 Nelson's Xanadu. (Source: Figure 1.3, Xanalogical structure, needed now more than ever: Parallel documents, deep links to content, deep versioning, and deep re-use, by Nelson TH. www.cs.brown.edu/memex/ACM_HypertextTestbed/papers/60.html.)

Douglas Engelbart's on-line system (NLS) (8) was the first working hypertext system, where documents could be linked to other documents and thus groups of people could work collaboratively. The video clips of Engelbart's historic demonstration of NLS from December 1968 are archived on the Web,1 and a recollection of the demo can be found in Ref. (9); a picture of Engelbart during the demo is shown in Fig. 1.3.

Figure 1.3 Engelbart's NLS. (Source: Home video of the birth of the hyperlink. www.ratchetup.com/eyes/2004/01/wired_recently_.html.)

About 30 years later in 1990, Tim Berners-Lee—then working for Cern, the world's largest particle physics laboratory—turned the vision of hypertext into reality by creating the World Wide Web as we know it today (10).2

The Web works using three conventions: (i) the URL (unified resource locator) to identify web pages, (ii) HTTP (hypertext transfer protocol) to exchange messages between a browser and web server, and (iii) HTML (hypertext markup language) (11) to display web pages. More recently, Tim Berners-Lee has been promoting the semantic web (12) together with XML (extensible markup language) (13), and RDF (resource description framework) (14), as a means of creating machine understandable information that can better support end user web applications. Details on the first web browser implemented by Tim Berners-Lee in 1990 can be found at www.w3.org/People/Berners-Lee/WorldWideWeb.

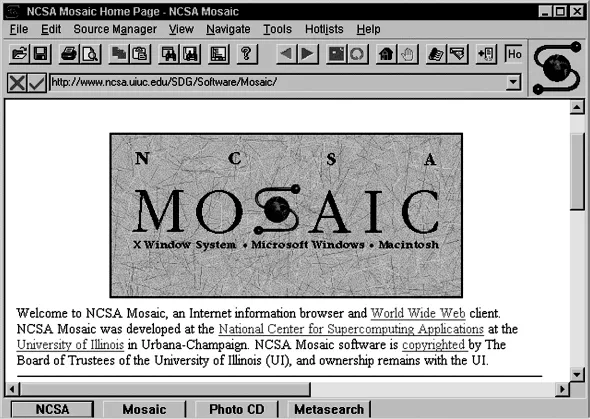

The creation of the Mosaic browser by Marc Andreessen in 1993 followed by the creation of Netscape early in 1994 were the historic events that marked the beginning of the internet boom that lasted throughout the rest of the 1990s, and led to the mass uptake in web usage that continues to increase to this day. A screenshot of an early version of Mosaic is shown in Fig. 1.4.

Figure 1.4 Mosaic browser initially released in 1993. (Source: http://gladiator.ncsa.illinois.edu/Images/press-images/mosaic.webp.)

1.3 Brief History of Search Engines

The roots of web search engine technology are in information retrieval (IR) systems, which can be traced back to the work of Luhn at IBM during the late 1950s (15). IR has been an active field within information science since then, and has been given a big boost since the 1990s with the new requirements that the Web has brought.

Many of the methods used by current search engines can be traced back to the developments in IR during the 1970s and 1980s. Especially influential is the SMART (system for the mechanical analysis and retrieval of text) retrieval system, initially developed by Gerard Salton and his collaborators at Cornell University during the early 1970s (16). An important treatment of the traditional approaches to IR was given by Keith van Rijsbergen (17), while more modern treatments with reference to the Web can be found in Refs 18, 1...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- List of Figures

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: The Web and the Problem of Search

- Chapter 3: The Problem of Web Navigation

- Chapter 4: Searching the Web

- Chapter 5: How Does a Search Engine Work

- Chapter 6: Different Types of Search Engines

- Chapter 7: Navigating the Web

- Chapter 8: The Mobile Web

- Chapter 9: Social Networks

- Chapter 10: The Future of Web Search and Navigation

- Bibliography

- Index