![]()

PART I

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

The challenges presented by increased longevity and increased percentages of older adults did not spring up all at once—they are issues we have chosen to neglect as they have steadily crept up over decades. Though the issues had been framed many times before, Jerome L. Kaufman’s 1961 report “Planning and an Aging Population” is a particularly eloquent and direct assessment of these challenges. In the introduction of his report, Kaufman states:

Kaufman goes on to call out some of the specific issues that will need to “sooner or later” be reconsidered:

In the fifty years since Kaufman asked these questions, seniors have achieved little advancement in comprehensive development planning, and most efforts at environmental planning for older adults have focused on specialized age-segregated retirement and care communities. Over the next fifty years and beyond, these measures will not be sufficient to accommodate older adults without enormous expense and/or neglect; hence, Kaufman’s questions must be raised again.

Part I reviews some of the critical contexts in which answers to these questions will need to be formulated. Accessibility laws did not exist in 1961, but today the basic regulatory structure for accessibility is in place and if repositioned strategically, it could provide a means of addressing critical upgrades to the general built environment. The healthcare system has grown exponentially since 1961, but it has done so with little relationship to the neighborhoods in which most of us will age. A robust wellness and fitness industry has grown since 1961 and has branched out into niche services, including many valuable supports for older adults. Accessibility regulations, healthcare systems, and wellness industries have provided new opportunities to once again raise Kaufman’s questions. Part I provides frameworks for structuring responses with these relatively recent opportunities.

1J. L. Kaufman, “Planning and an Aging Population,” Information Report No. 148 (Chicago, IL: American Society of Planning Officials, July 1961).

2Kaufman, “Planning,” 1.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE LONGEVITY CHALLENGE TO URBANISM

With contributions from Susan Brecht, Kathryn M. Lawler, and Glen A. Tipton

The Challenge

Longevity was the great gift of the twentieth century. Learning what to do with this gift is the great challenge of the twenty-first century.

Americans born in 1900 would not have been able to drive a car, ride in an airplane, see a motion picture, work a crossword puzzle, use a washing machine, or talk on the phone. But they could do all of this and more by the time they were 30. Within the next forty years, they would have witnessed the construction of the interstate highway system, experienced the great suburban expansion, and even watched the first man walk, and then drive, on the moon. Cross-country and international travel, unheard of at the turn of the century, would have become a regular and frequent experience for thousands by the end of the century.

The tremendous creativity and innovation of the twentieth century changed the lives of individuals and families, radically redefining how we live in our neighborhoods, cities, and counties and how we carve out a role in an increasingly international economy and culture. Consider that Americans born before 1900 were far more likely to live just like those living in the two or three prior centuries—heating their homes by fire, growing almost all of their own food, walking or riding a horse for transportation, and communicating via postal mail at best. The incredible advancements of the twentieth century were not only numerous, they occurred at an almost incomprehensible pace. What is remarkable is that one of the most significant advances—longevity—went largely unnoticed and unaccounted for.

As with generations that came before them, most Americans born in 1900 would have lived on the same street as their parents and maybe even their entire extended families. But it’s also just as likely that their children and grandchildren would live hundreds of miles away. Twentieth-century progress spread families and neighborhoods across much larger geographic areas than had ever been previously feasible. As homes dispersed across the landscape, public transit disappeared and the interstate highway system facilitated suburban sprawl, with its relatively uniform housing stock, reduced walkability, and lack of transportation choices, families and communities changed to fit their new environments. The attenuation of settlement patterns and social networks challenged urbanism: the spatial and cultural phenomena of place.

Now that the first suburbanites are aging, it’s becoming quite clear that the twentieth-century progress that allowed us to spread out, live in larger homes with larger yards, and drive our cars to work, shop, and play cannot accommodate the brand new, and without precedent, experience of living much longer. Suddenly, communities that were sold as a healthy refuge for families from the polluted and congested neighborhoods of the city are unable to support anyone who can’t take care of their home and yard and drive their own car. Without sidewalks, trails, and, most importantly, destinations, these suburban neighborhoods make it difficult to maintain health and remain free of chronic disease. It’s now very clear that suburbia was built while science and medicine were making it possible to live longer. But the designers, planners, architects, and financiers who made suburban living possible, along with the suburbanites themselves, invested billions of dollars without ever considering that the residents would grow and stay old much longer than ever before.

The gift of longevity very well may be the catalyst that returns Americans to a full appreciation of the urbanism we once had and can have again. We grow more reliant on close proximities in both physical and social relationships as we advance in age. “Urbanism” refers to close relationships in both respects: the compactly built environment and the collective sense of identity that such an environment fosters. Closeness is the operative condition of both the physical and social structures of urbanism. Until a movement is launched to shorten the lifespan or to halt the scientific and medical progress that is almost exclusively focused on extending life even further, communities will be forced to look back at how we used to live together—in urban environments—to ensure that longevity is a gift we are truly equipped to receive.

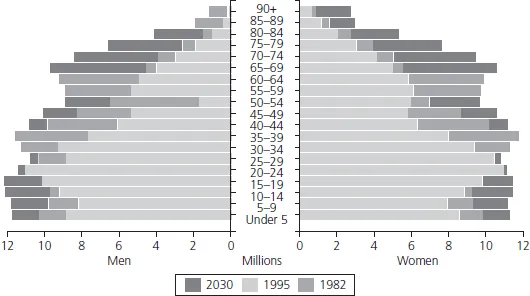

Demographic Revolution

For the first time ever, the older adult population will match in size the youngest populations on the planet. The traditional population pyramid will morph to a population rectangle (fig. 1.1). In the entire time human beings have populated the earth, this has never before happened. Communities have always been organized around a very young population, with the highest percentage of individuals being between zero and five years of age. Even as life expectancy grew, and people were more likely to survive childhood illnesses and live into adulthood, the relationship between the young and the old remained almost the same as it had always been. It was only when the increase in the older adult population began to outpace the growth in the youngest populations that the transformation began. With decreasing birth rates and increased longevity, this trend will continue well into the twenty-first century. While most people have become increasingly aware of this unprecedented demographic shift, the basic statistics are worth a review (fig. 1.2).

- By 2030, the United States will be home to approximately 71 million people over the age of 65, making one out of every five US residents an older adult.2

- The growth in the older adult population is driven by both the aging of the baby boomer generation and increased life expectancy. As a result, there will be a larger number of both older adults and old-older adults (those over the age of 85) than ever before.

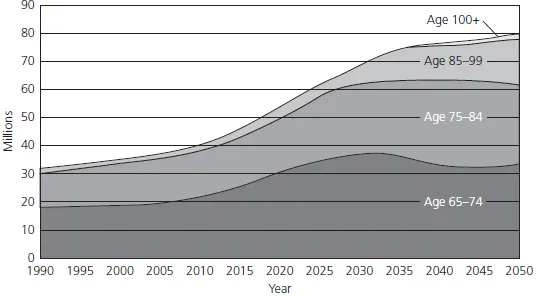

- Of the approximately 71 million people over the age of 65 in 2030, 5 million will be over the age of 85, and still only a small number will be over the age of 100. In ten years (by 2040) however, it’s estimated that 12 million people will be between the ages of 85 and 99, and 1 million people will be over the age of 100 (fig. 1.3).3

- The dependency ratio—the proportion of working-age populations (ages 15 to 64) compared to nonworking-age populations (ages 0 to 15 and ages greater than 64)—will also experience a record high, as fewer working people are available to support those who do not work. This means that there will be more people demanding services and less people available to deliver these services. Companies across the globe are working to understand and prepare for how this will impact their labor force. For example, 60 percent of all nonseasonal federal employees will be eligible for retirement by 2016.5

- Current debates about deficit reduction highlight how the magnitude of this population dramatically affects both revenues and spending in the United States. Social Security was created when there were twelve workers for every one beneficiary and when average life expectancy was about 62. But by 2050, there will be t...