This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The relationship between space and politics is explored through a study of French urban policy. Drawing upon the political thought of Jacques Rancière, this book proposes a new agenda for analyses of urban policy, and provides the first comprehensive account of French urban policy in English.

- Essential resource for contextualizing and understanding the revolts occurring in the French 'badland' neighbourhoods in autumn 2005

- Challenges overarching generalizations about urban policy and contributes new research data to the wider body of urban policy literature

- Identifies a strong urban and spatial dimension within the shift towards more nationalistic and authoritarian policy governing French citizenship and immigration

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Badlands of the Republic by Mustafa Dikec in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Urban Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Badlands

1

Introduction: The Fear of ‘the Banlieue’

The accusations were serious: armed robbery, killing of three police officers and murder of one taxi driver. They were hurled at a young woman of 23 years old and her companion, a young man of about the same age, who was shot dead during his sconfrontation with the police. The evidence presented at the court, and the presence of eyewitnesses, left little hope for the young woman. The prosecuting attorney insisted on the truly cynical nature of the acts of the two, which, it was maintained, could not be justified by the circumstances. The prosecutor claimed:

[They] are not terrorists, they are not Bonnie and Clyde, they are not the characters of Natural Born Killers. They are neither zonards,1 nor drug addicts, nor banlieue outcasts [des exclus de banlieue]. [She] is not the daughter of immigrants, her mother was a teacher and helped her with homework in the evenings. These are two students who dropped out of college, gave up on work, who chose to live in a squat and to live from hold-ups, because ‘money is freedom’. (Libération, 30 September 1998: 15; emphasis added)

What the accused were not associated with – terrorism, drugs, exclusion, immigration – exemplifies some of the terms that have been articulated with the spatial references of the prosecuting attorney – zones and banlieues – in the last two decades. Was the attorney, with these statements, recognizing the difficulties of growing up or living in a zone (being a ‘zonard’) or banlieue? Or was she, if unwittingly, demonstrating the naturalization of crime as associated with zones and banlieues? If the accused were zone or banlieue inhabitants, would their acts be seen as more ‘natural’ rather than truly cynical? In a republic that cherishes so dearly the principle of equality, how can such spatial references be presented as potentially mitigating circumstances?

The attorney’s argument gives us a sense of the pervasiveness of the negative image of banlieues, and shows how common and accepted this image has become (although there are many prestigious banlieues as well). This book is about a specific urban policy programme conceived to address the problems of social housing neighbourhoods in banlieues of French cities, which, as I will try to show, contributed largely to the consolidation of negative images associated with them. This programme was initiated by the Socialist government as an urgent response to the so-called ‘hot summer’ of 1981, marked by revolts in the banlieues of several cities. ‘Urban policy’, hereafter, refers to this particular policy. Conceived originally as a ‘spatialization of social policies’ (Chaline, 1998), it was regrouped later in 1988 under the generic term ‘la politique de la Ville’ as a national urban policy with the banlieues as its main object. As the issues around banlieues have wider resonance, with connotations ranging from threats to French identity to terrorism, French urban policy, as Béhar (1999) wrote, has probably been the most debated public policy of the last two decades. This book provides a wide-ranging analysis of this policy by bringing together policy discourses and alternative voices expressed in its intervention areas. It offers an approach to urban policy that makes space central, and looks at the ways in which space is imagined and used in policy formation in the broader context of state restructuring. In so doing, it provides insight into the relationship between space and politics.

The French case is particularly important for exploring the relationship between space and politics, as space – and not community, as in the British and North American urban policy experience – has been the main object of French urban policy. This is almost necessarily so since the French republican tradition emphasizes a common culture and identity, and any reference to communities is deliberately avoided because they imply separatism, which is unacceptable under the principle of the ‘one and indivisible’ republic. Yet, while space remained the main object, there have been considerable changes in how space has been imagined and manipulated over the two decades of this policy. This book makes these changes and their varying political implications central to its approach to urban policy. It shows how French urban policy has constituted its spaces of intervention, associated problems with them, legitimized particular forms of state intervention, and how alternative voices formulated in such spaces challenged official designations. It situates its analysis in a broader political and economic context, showing how it feeds down into urban policy.

This book’s approach to urban policy follows from a central premise to consider space not as given, but as produced through various practices of articulation. Since urban policy conceives of its object spatially, I see urban policy as a practice of articulation that constitutes space, an institutionalized practice that defines spaces (i.e. its spaces of intervention). Thus, I maintain that urban policy constitutes its spaces of intervention as part of the policy process, rather than by acting on given spaces.

However, each policy discourse and programme is guided by particular ways of imagining space. For example, spaces of intervention may be imagined as self-contained areas with rigid boundaries, as parts of a larger network, or as part of a relational geography. Each of these ways of conceiving space has different implications for the constitution of perceived problems and the formulation of solutions to them, ranging from limited local initiatives to regional distributive policies. Thus, I insist that conceptualizations of space matter in policy, and look at the ways in which space is conceived and their policy and political implications.

Although urban policy is one way of constituting space, it is not the only one. Therefore, I bring together official discourses and alternative voices, and insist that analyses of urban policy consider policy from above and voices from below as a contestation for space. In other words, rather than merely focusing on the official discourses on banlieues, I try to give voice to alternative discourses formulated in banlieues.

My analysis, further, situates French urban policy in a wider political and economic context, and focuses on how it has constituted its spaces of intervention and how alternative voices have challenged its official descriptions. Theoretically informed by Jacques Rancière’s political thought which draws attention to the relationship between space and politics – and using Philip Corrigan and Derek Sayer’s (1985) notion of ‘the state’s statements’ – which draws attention to state’s practises of articulation – I see urban policy as a particular regime of representation that consolidates a certain spatial order through descriptive names, spatial designations, categorisations, definitions, mappings and statistics. In this sense, it is a place-making practice that spatially defines areas to be treated, associates problems with them, generates a certain discourse, and proposes solutions accordingly. I do not, therefore, see urban policy as a merely administrative and technical issue, and argue against such an approach that it is tightly linked to other issues, ranging from immigration politics to economic restructuring. Instead, I adopt an eclectic approach that carries some of the features of political economy, social constructionist and governmentality approaches to urban policy. Political economy approaches relate urban policy to the larger restructurings of the state, and highlight processes of neoliberalization, premised on the extension of market relations that privilege competition, efficiency and economic success. While endorsing the attention given to the relationship between urban policy and state restructuring, I argue that there are other political rationalities that affect contemporary transformations of states and urban policy, and that equal attention should be given to established political traditions – in this case, the French republican tradition, which emphasizes the social obligations of the state towards its citizens as well as a common culture and identity, seen to be the basis of the integrity of the ‘one and indivisible’ republic. Such an emphasis on state restructuring and established political traditions shows that the contemporary restructuring of the French state involves an articulation of neoliberalism with the French republican tradition, producing a hybrid form of neoliberalism. It also points to the relationship between urban policy and state restructuring, which, in the French case, is manifest in the consolidation of the penal state mainly in and through the spaces of urban policy.

Although there are many parallels between the approach I adopt in this book and social constructionist and governmentality approaches, two major differences remain. First, I try to avoid the implication (usually associated with constructivist approaches; see Campbell, 1998 for a critique) that policy makers and other state actors are consciously and deliberately engaged in a discursive construction of ‘reality’ from a privileged place outside the domain of their very engagement, with the tools and force of language at their disposal. What interests me here is the ways in which policies put in place certain ‘sensible evidences’ (policy documents, spatial designations, mappings, categorizations, namings and statistics) and their effects: that is, how they help to consolidate a particular spatial order and encourage a certain way to think about it. As we will see, the kinds of sensible evidences employed, their significance and effects depend highly on the broader political and economic context; they do not, in other words, materialize in a vacuum.

Second, I argue that analyses of urban policy guided by these approaches have given insufficient attention to the issue of space (which is also observed by some scholars committed to these approaches; see, for example, Murdoch, 2004; Raco, 2003). Social constructionist approaches, while helpfully focusing on the construction of urban problems and policy discourses, neglect the role that space plays in such constructions. Governmentality approaches, on the other hand, present such an overarching argument that there is little or no room left for the difference that space makes in policy formation and resistance to it. I share the view with the social constructionist approaches that problems and policies associated with spaces of urban policy are constructed – rather than already given – but insist that equal attention be given to the ways in which such spaces are imagined and used in the formation of problems and policies. With the governmentality approaches, I concur that the construction of spaces through urban policy has a governmental dimension, but maintain that there is no inherent politics to such constructions. In other words, variations in the ways space is imagined and manipulated matter.

Approached this way, the French experience offers us the following four lessons on the nature of urban policy and on the relationship between space and politics. First, urban policy has to be understood in a range of established political traditions – in this case, French republicanism – and major national and international events – from riots in Brixton to demonstrations of high school students in Paris, from the Rushdie affair to the Islamic headscarf affair, from the Intifada to riots in Los Angeles. Second, the spaces of urban policy cannot be taken for granted, and any analysis of urban policy has to critically analyse the ways in which policies constitute their spaces of intervention. Third, ways of imagining space influence both the definition of problems associated with intervention areas and policy responses to them. In more general terms, different ways of imagining space have different political implications. Finally, both governance and resistance are spatial, place-making practices. In this sense, there is an ongoing contestation for space: what the official policy discourse constitutes as ‘badlands’ also become sites and organizing principles of political mobilization with democratic ideals.

The ‘badlands’ in question are the banlieues of French cities: that is, neighbourhoods in the peripheral areas of cities. In order to understand what is at stake in French urban policy, we need first to get a sense of what the banlieues stand for.

The Colour of Fear

Banlieue literally means suburb, but it carries different connotations from the ones associated with the British or North American suburb. Originally an administrative concept, the term banlieue geographically denotes peripheral areas of cities in general.2 Such a geographical designation is not necessarily negative (as in ‘the banlieue’). Nevertheless, the term evokes an image of excluded places, as its etymological origin suggests:

‘Ban’ comes from the earliest medieval times, when it meant both the power of command and the power of exclusion as part of the power of command. Banned [Banni], banishment [banissement], banlieue – all these terms have the same origin; they refer to places of exclusion. Clearly, banlieues have existed independently from terms to designate them, they have made and often managed their own history, they have not simply been excluded places, but their existence does nevertheless express this will to create on the outskirts of the city places that do not belong to the system. (Paul-Levy in Banlieues 89, 1986: 125)3

Now the term mostly evokes an image of a peripheral area with concentrations of large-scale, mostly high-rise social housing projects, and problems associated, in the US and the UK, with inner-city areas. It no longer serves merely as a geographical reference or an administrative concept, but stands for alterity, insecurity and deprivation. In order to emphasize the term’s origin and geographical connotations, I use ‘banlieue’ instead of ‘suburb’ throughout the text.

In the early 1980s, Rey (1999: 274) writes, the banlieues of large French cities began to ‘arouse a feeling of fear’, a feeling that continued to increase in the decades to follow, becoming one of the major ‘phobias’ of the French in the new millennium (Libération, 8 April 2002: 4–5). The term ‘banlieue’ designates the social housing estates of popular neighbourhoods in the peripheral areas of cities as threats to security, social order and peace. This threat, furthermore, has become closely associated with the populations living in banlieues, often defined in ‘ethnic’ terms. The fear of the banlieue is closely associated with a feeling of insecurity and a fear of immigration (Rey, 1999).

A similar observation is made by Hargreaves, who argues that the 1990s was a turning point in the eventual association of the banlieue with a feeling of insecurity and a fear of immigration:

During the 1990s, a new social space has been delineated in France: that of the ‘banlieue(s)’ (literally, ‘suburb(s)’). A term that once served simply to denote peripheral parts of urban areas has become a synonym of alterity, deviance, and disadvantage. The mass media have played a central role in this reconstruction, in the course of which they have disseminated and reinforced stereotypical ideas of people of immigrant origin as fundamentally menacing to the established social order. (Hargreaves, 1996: 607; emphasis added)

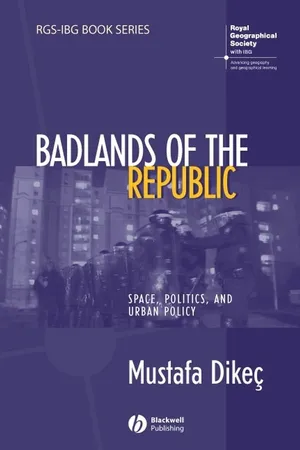

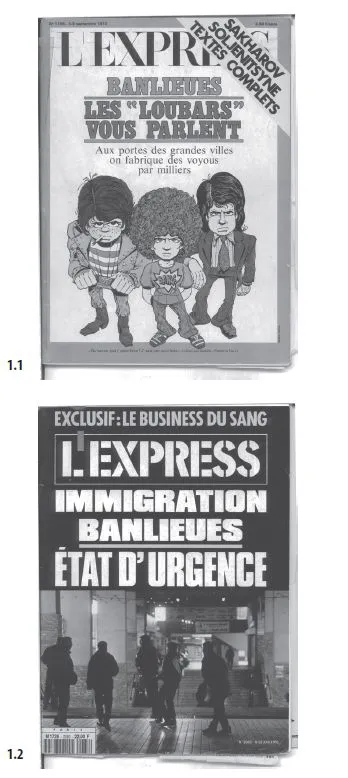

Hargreaves exemplifies the media creation of ‘the banlieues as a news category’ and the amalgamation of ‘urban deprivation, immigration, and social order’ in the 1990s with an issue of the journal L’Express, which presented a cover story under the title ‘Banlieues – Immigration: State of Emergency’ (5–12 June 1991). The same journal, however, had presented another similar cover story almost two decades earlier under the title ‘Banlieues: “Hooligans” are Talking to You’. The subtitle read: ‘At the gates of large cities, thousands of hoodlums are produced’ (3–9 September 1973). As the cover drawing and the photos depicted them, the hooligans and hoodlums of L’Express in 1973 were all white. They would change colour in 1991, but the spatial reference would remain the same. In this sense, L’Express best exemplifies the changing colour of the fear of ‘the banlieue’ from the 1970s into 1990s (Figures 1.1 and 1.2).

Media reviews provide clear examples of the changing image of the banlieues in the last two decades (see, for example, Collovald, 2000, 2001; Hargreaves, 1996; Macé, 2002). However, the current image of the banlieues is not simply the product of journalistic accounts. Many of the journalistic categories used to frame banlieues have been institutionalized by state policies. The period in which the banlieues became articulated with issues of immigration, insecurity and social order was a period of intense official engagement with the question of banlieues – notably through urban policy, which became increasingly concerned with issues of immigration and insecurity, often to the detriment of its initial social and democratic ideals. It is these changes that I will chart in the following chapters, placing them in broader political and economic context, and relating them to the contemporary restructuring of the French state along increasingly authoritarian and exclusionary lines.

Figures 1.1 and 1.2 The changing colour of ‘the banlieue’ (1.1 (head): ‘Banlieues: "Hooligans" are Talking to You’. Source: L’Express, 3–9 September, 1973; 1.2 (foot): ‘Banlieues – Immigration: State of Emergency’. Source: L’Express, 5–12 June, 1991)

As I will try to show, the contemporary restructuring of the French state is marked by a strong attachment to the republican tradition. The French conception of the republic emphasizes a common culture and identity, fragmentation of which is seen as a threat to the social and political integrity of France. The republican tradition is based on the presupposition that ‘without a common culture and a sense of common identity, the political as well as physical integrity of France would be “threatened”’ (Jennings, 2000: 586). There is, therefore, little or no room for claims rising from ‘differences’. The French citizen is a universal individual-citizen, directly linked to the nation-state, and national-political membership requires the acceptance of French cultural values (Feldblum, 1999; Safran, 1990). There is no official recognition of ethnicity, race or religion as intermediary means for obtaining particular rights, and the very notion of minority is strongly rejected (de Rudder and Poiret, 1999). Such a conception, in the context of fascinating diversity, generates a firm suspicion towards all kinds of particularisms. As Jennings argues,

[T]he political project of nation-building pursued by the French state led not only to a weak conception of civil society but also to the persistent fear of the dangers of ‘communities’ operating within the public sphere. Within this project, citizenship was grounded upon a set of democratic political institutions rather than upon a recognition of cultural and/or ethnic diversity. Republicanism itself thus became a vehicle of both inclusion and exclusion. (2000: 597)

It is from this deep attachment to the republican tradition that follows what Hargreaves (1997: 180) calls a republican myth of the French nation characterized by an ‘apparent blindness or outright hostility to cultural diversity’, which not only leaves little or no room to cultural ‘differences’ (Wieviorka, 1998), but also enhances ‘a system of intimidation that interdicts all protest social movements on the part of minority groups, without providing them the means to fight against inequalities and oppression of which they remain the victims’ (de Rudder and Poiret, 1999: 398–99).

Such a concern with French identity and cultural differences was perhaps best exemplified by a 1992 report of the Haut Conseil à l’Intégration (HCI), a council created in 1989 to advise the government on the issue of integration based on a ‘republican model’.

Notions of a ‘multicultural society’ and the ‘right to be different’ are unacceptably ambiguous. It is true that the concept of the nation as a cultural community [ . . . ] does appear unusually open to outsiders, since it regards an act of voluntary commitment to a set of values as all that is necessary. But it would be wrong to let anyone think that different cultures can be allowed to become fully developed in France. (HCI, 1992; cited in Hargreaves, 1997: 184)

It should be noted, however, that there has been a renewed enthusiasm for the republican tradition with nationalistic overtones since the 1990s, which I refer to as ‘republican nationalism’. The rise of republican nationalism has been observed by many scholars with regard, in particular, to citizenship and immigration policies (see, for example, Balibar, 2001; Blatt, 1997; Feldblum, 1999; Tévanian and Tissot, 1998). As we will see, urban policy has also been influenced by the development and deployment of republican nationalism since the 1990s.

Before moving on, a preliminary explanation of certain notions might be helpful as the republican tradition shapes political debate and policy discourse in a particular way. We will see that the following four notions are commonly used in policy discourse and debates around the banlieues: ‘communitarianism’, ‘ghetto’, ‘social mixity’ and ‘positive discrimination’. These notions may sound ordinary and their meanings self-evident (except, probably, the last one), but they connote particular issues and carry remarkable political weight in the French co...

Table of contents

- Cover

- series

- tittle

- copyright

- Dedication

- List of Figures and Tables

- List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Series Editors’ Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part I: Badlands

- Part II: The Police

- Part III: Justice in Banlieues