- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Visualization of Spatial Social Structure

About this book

The visualization of spatial social structure means, literally, making visible the geographical patterns to the way our lives have come to be socially organised, seeing the geography in society. To a statistical readership visualization implies using data. More widely defined it implies freeing our imaginations.

The Visualization of Spatial Social Structure introduces the reader to new ways of thinking about how to look at social statistics, particularly those about people in places. The author presents a unique combination of statistical focus and understanding of social structures and innovations in visualization, describing the rationale for, and development of, a new way of visualizing information in geographical research. These methods are illustrated through extensive full colour graphics; revealing mistakes, techniques and discoveries which present a picture of a changing political and social geography. More complex aspects on the surface of social landscapes are revealed with sculptured symbols allowing us to see the relationships between the wood and the trees of social structure. Today's software can be so flexible that these techniques can now be emulated without coding.

This book centres on a particular place and time; 1980s Britain, and a particular set of records; routine social statistics. A great deal of information about the 80s' social geography of Britain is contained within databases such as the population censuses, surveys and administrative data. Following the release of the 2011 census, now is a good time to look back at the past to introduce many new visualization techniques that could be used by future researchers.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1.1 Visual thinking

1.2 Pictures over time

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- List of figures

- List of text boxes

- Preface

- Introduction: Human cartography

- Chapter 1: Envisioning information

- Chapter 2: People, spaces and places

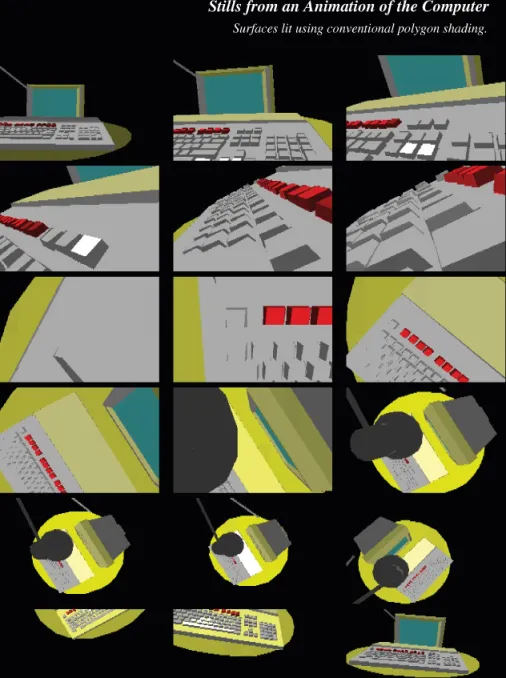

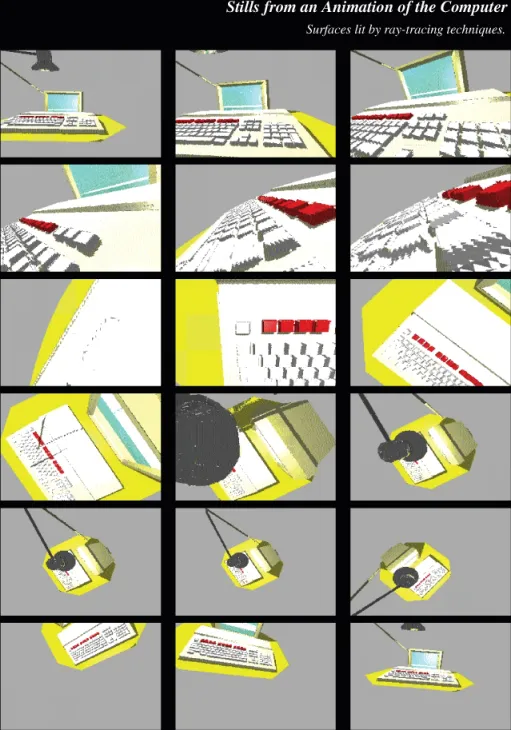

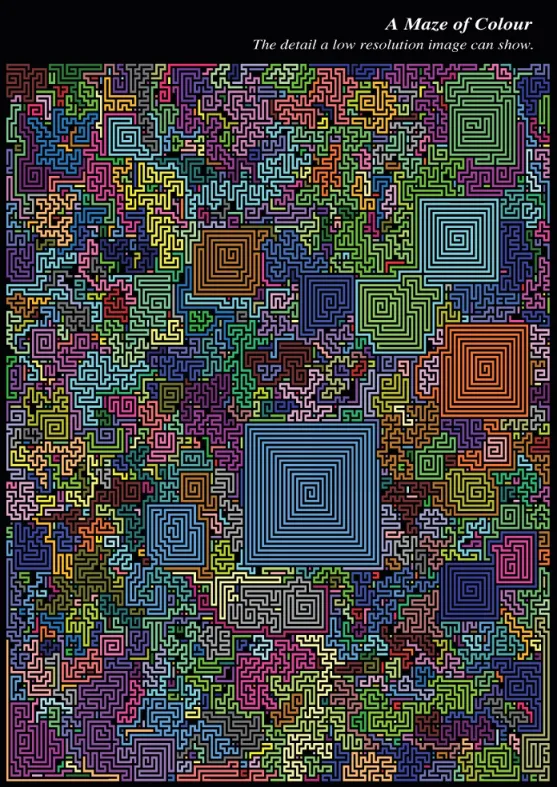

- Chapter 3: Artificial reality

- Chapter 4: Honeycomb structure

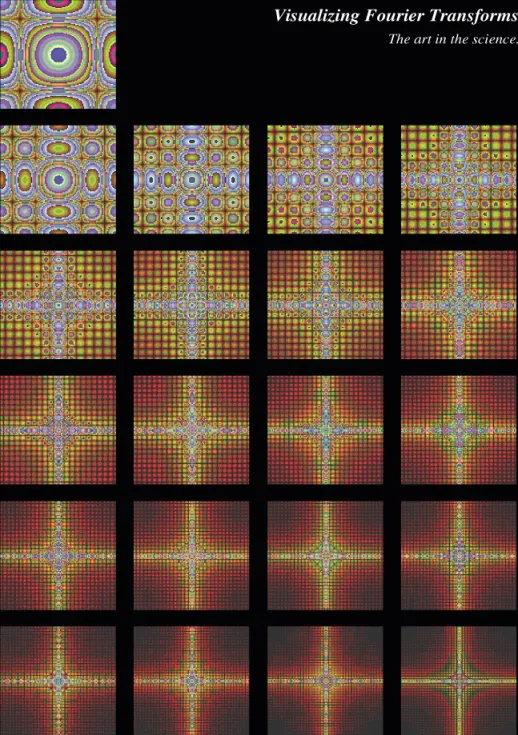

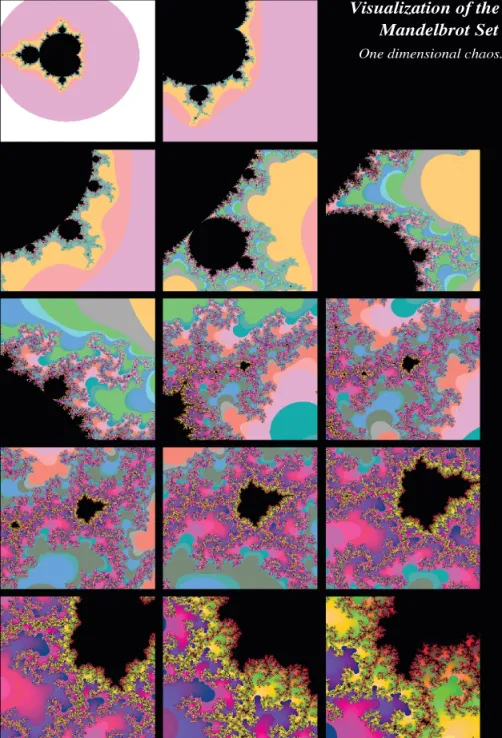

- Chapter 5: Transforming the mosaic

- Chapter 6: Cobweb of flows

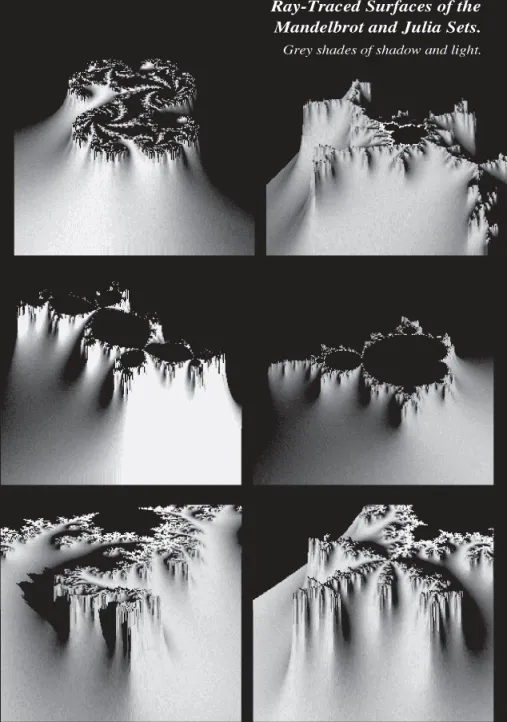

- Chapter 7: On the surface

- Chapter 8: The wood and the trees

- Chapter 9: Volume visualization

- Chapter 10: Conclusion: Another geography

- Endnote

- Acknowledgements

- Appendix: Drawing faces

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app