eBook - ePub

Small Animal Bandaging, Casting, and Splinting Techniques

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Small Animal Bandaging, Casting, and Splinting Techniques

About this book

Small Animal Bandaging, Casting, and Splinting Techniques is a well-illustrated how-to manual covering common bandaging methods used to support and manage both soft tissue and orthopedic conditions in small animal patients. This highly practical book offers step-by-step procedures with accompanying photographs to aid in the secure and effective application of bandages, casts, and splints, with coverage encompassing indications, aftercare, advantages, and potential complications for each technique. Small Animal Bandaging, Casting, and Splinting Techniques is an indispensable guide for busy veterinary technicians and nurses, as well as veterinarians and veterinary students.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Basics of Bandaging, Casting, and Splinting

Bandaging

Purposes and functions of a bandage

Bandages serve many functions in wound management (table 1.1). In general, bandages provide an environment that promotes wound healing.

Table 1.1. Properties of a bandage.

|

Hedlund, Cheryl S. 2007. Surgery of the integumentary system. In Small Animal Surgery, 3rd ed., pp. 159–259. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, Elsevier.

Sources: Williams, John, and Moores, Allison. 2009. BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Wound Management and Reconstruction, 2nd ed., pp. 37–53. Quedgeley, Gloucester, England: British Small Animal Veterinary Association.

Components of a bandage

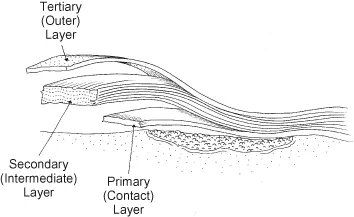

There are three components or layers of a bandage. These are the primary, secondary, and tertiary bandage layers (fig. 1.1).

Fig. 1.1. The three layers of a bandage: primary-contact layer, secondary-intermediate layer, and tertiary-outer layer.

Primary-contact layer

The primary layer is also called the contact layer. It is directly in contact with the wound. Depending on the stage of healing, this layer can be used to debride tissue, absorb exudates, deliver medication, or form an occlusive seal over the wound. The primary layer plays a vital role in providing a wound environment that promotes healing rather than a layer that just covers the wound. The properties of primary dressing materials vary widely, and it is important to select a primary dressing that is appropriate to the wound in its current stage of healing and to change the type of dressing as healing progresses. Occlusiveness and absorption are important properties of the contact dressing.

Highly absorptive dressings

Highly absorptive dressings are indicated in the treatment of wounds that are heavily contaminated or infected, have foreign debris present, and/or are producing large amounts of exudate. Such wounds are generally in the early inflammatory stage of wound healing. Once a wound has entered the later inflammatory or early repair stage, another form of dressing is selected that will promote the progression of the healing process, for example, a moisture-retentive dressing.

Gauze dressings

Gauge dressings are used in wet-to-dry and dry-to-dry bandages. These forms of bandage are older techniques for bandaging and provide a means of clearing a wound of exudates and necrotic tissue in the early days of wound management. For instance, dry gauze may be the most economical primary dressing in a highly productive wound where absorptive bandage changes are needed multiple times daily. However, after three to five days, a contact layer that will promote wound repair is indicated, for example, calcium alginate, hydrogel, or foam dressing.

With wet-to-dry dressings wide mesh gauze is wetted with sterile saline, lactated Ringers solution, or 0.05% chlorhexidine diacetate solution and is placed in wounds with viscous exudate or necrotic tissue. The exudates are diluted and absorbed into the secondary bandage layer. As the fluid evaporates, the bandage dries and adheres to the wound. When the dressing is removed, adhered necrotic tissue is also removed. Removal is usually painful. Thus, moistening the gauze with warm 2% lidocaine that does not contain epinephrine makes removal more comfortable. In cats, moistening the gauze with warm physiologic saline is indicated.

For dry-to-dry dressings, dry gauze is placed in a wound that has low-viscosity exudate. The exudate is absorbed and evaporates from the bandage, leaving the dressing adhered to the wound. Removal of the dressing removes necrotic tissue. Moistening the gauze with warm 2% lidocaine makes removal more comfortable. Moistening the gauze with warm physiologic saline should be done in cats.

These gauze dressings have several disadvantages: (1) Both healthy and unhealthy tissue are removed at dressing change. (2) The dry environment does not favor the function of cells and proteases involved in healing. (3) There is danger of exogenous bacteria wicking inward toward the wound with a wet gauze, and if the dressing is maintained wet tissue maceration can occur. (4) Dry gauze can disperse bacteria into the air at bandage change. (5) Fibers of the gauze can remain adhered to the wound to induce inflammation. (6) The adherent dressings are more painful to wear and to remove. (7) Removal of wound fluid with the dressings removes cytokines and growth factors essential for optimal healing.

Hypertonic saline dressings

These dressings are a good choice for infected or necrotic, heavily exudative wounds that need aggressive debridement. Their 20% sodium chloride content gives them an osmotic effect to draw fluid from the wound to decrease edema and thus enhance circulation. The osmotic action also desiccates tissue and bacteria. These dressings are changed every one to two days until necrosis and infection are under control. The debridement of this osmotic dressing is nonselective in that both healthy and necrotic tissue are removed at dressing change. The dressings are used early in wound treatment to convert a necrotic sloughing wound to a moderately exudating granulating wound. At this time the primary dressing is changed to a calcium alginate, hydrogel, or foam dressing.

Calcium alginate dressings

These hydrophilic dressings are indicated in moderate to highly exudative wounds, that is, wounds in the inflammatory stage of healing. However, their placement over exposed bone, muscle, tendon, and dry necrotic tissue is not recommended. Neither should they be used on dry wounds or those covered by dry necrotic tissue. They are available as a feltlike material in pad or rope form. The calcium alginate, which is derived from seaweed, interacts with sodium in wound fluids to create a sodium alginate gel that maintains a moist wound environment.

Attention should be paid to the hydration of wound tissues when using calcium alginate dressings. To help maintain a moist environment, the dressing can be overlaid with a vapor-permeable polyurethane sheet. However, if too much exudate is being produced in the presence of the dressing, it can be covered with an absorptive foam dressing. Because it is so absorptive, it can dehydrate a wound as the healing progresses and exudate decreases. If it is left in a wound too long, it dehydrates and hardens to form a calcium alginate eschar that is difficult to remove. Rehydrating it back to a gel with saline aids in its removal.

These dressings aid in the transition from the inflammatory to the repair phase of healing by promoting autolytic debridement and granulation tissue formation. The dressing can be premoistened with saline to promote granulation tissue in wounds without considerable exudate. Additional benefits of this dressing include a hemostatic property and entrapment of bacteria in the gel that can be lavaged from the wound at dressing change.

Copolymer starch dressings

This type of highly absorptive dressing is indicated for necrotic infected wounds that are moderately to highly exudative. If an occlusive cover is needed to hold them in place or retain some moisture, they can be overlaid with a hydrocolloid dressing. At dressing change, the polymer is removed by lavage.

It is important to observe the exudate level in wounds being treated with copolymer starch dressings. If exudate levels become too low, the dressing adheres to the wound. This can result in tissue damage when it is removed and inflammation if fragments of dressing are left in the wound.

Moisture-retentive dressings

Moisture-retentive dressings (MRDs) provide a warm, moist environment over a wound in which cell proliferation and function are enhanced in the inflammatory and repair stages of healing. In addition, the retained fluid provides a physiologic ratio of proteases, protease inhibitors, growth factors, and cytokines at each stage of healing. Thus, exudate can be beneficial in healing. Clinical judgment should be used in deciding whether treatment should begin with one of the highly absorbent dressings first and then change to an MRD or whether treatment can begin with an MRD. In general, a highly absorptive dressing should be considered initially if there is a great amount of necrosis, foreign debris, infection, and exudate.

The wound environment under an MRD provides several advantages in the progression of wound healing (table 1.2). There are disadvantages of MRDs in that retained fluid can cause maceration (softening caused by trapped moisture) and excoriation (damage caused by excess proteolytic enzymes) of the periwound skin.

Table 1.2. Advantages of moisture-retentive dressings (MRDs)*.

|

*MRDs will vary in their possession of these advantages.

Source: Campbell, Bonnie Grambow. 2006. Dressings, bandages, and splints for wound management in dogs and cats. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice. 36(4):759–91. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier.

Polyurethane foam dressings

The dressings are soft, compressible, nonadherent, highly conforming dressings. They are highly absorptive by wicking action and are designed for use in moderate to highly exudative wounds. The foam dressings maintain a moist environment and support autolytic debridement. In addition, they can promote the formation of healthy granulation tissue and have been reported to promote epithelialization. Thus, they are a dressing that can be used in both the inflammatory and the repair stages of healing. An alternative way to use the foam is to saturate it with liquid medication for delivery to the wound.

The frequency of bandage change with foams is related to the stage of wound healing. It can vary from one to seven days, with the shorter times between changes being in the early stages of management when there is considerable fluid production.

Polyurethane film dressings

These film dressings are thin, transparent, flexible, semiocclusive (permeable to gas but not water or bacteria) sheets. They have an adhesive perimeter for attaching them to periwound skin, and their transparency allows wound visualization. They are nonabsorptive and should be used on wounds with no or minimal exudate. For instance, they are suited for dry necrotic eschars, or shallow wounds, such as partial-thickness wounds like abrasions. They can also be used on wounds in the advanced repair stage of healing where there is need for a moist environment to promote epithelialization. Another use of the films is as a cover over other contact layers to support moisture retention and to provide a bacteria and waterproof cover.

The films should not be used on wounds that have high levels of exudate, are infected, or have fragile periwound skin. Neither should they be used on wounds over exposed bone, muscle, or tendon or on deep burns.

The dressings do not adhere well to areas with skin folds or unshaved hair. Hair growth on the periwound skin can push the adhesive attachment of the dressing off of the skin. However, adherence can be improved around the perimeter of the wound with vapor-permeable film spray.

With this type of dressing, the cloudy white to yellow exudate that accumulates under the dressing should not be interpreted as infection. It is just wound surface exudate. Infection will present as heat, swelling, pain, and hyperemia of the surrounding tissues.

Hydrogel dressings

Hydrogels are water-rich gel dressings that are in the form of a sheet or an amorphorus hydrogel. Some hydrogels contain other medications that can be beneficial to wound healing, such as acemannan, a wound healing stimulant, and metronidazole or silver sulfadiazine, antimicrobials.

Because they donate moisture to a wound, the hydrogels can be used in wounds with an eschar or dry sloughing tissue to rehydrate the tissues. To assure that wound moisture is transferred to the tissue and not the secondary bandage layer, the hydrogel can be overlaid with a nonadherent semiocclusive dressing or vapor-permeable polyurethane foam. Some hydrogels have an impermeable covering as part of the dressing. Conversely to donating fluid to wounds, some hydrogels are able to absorb considerable fluid and can be used in exudative wounds. These dressings can also be used in necrotic wounds to provide a moist environment to promote autolytic debridement and aid in granulation tissue formation.

In noninfected full-thickness wounds, the dressings are generally changed every three days. However, if a hydrogel containing a wound healing stimulant or antimicrobial is being used, daily change may be indicated to maintain their activity in the wound. With abrasions that have minimal exudate, hydrogels may be changed every four to seven days. At dressing change, the hydrogel is removed from the wound with gentle saline irrigation.

Hydrocolloid dressings

Hydrocolloid dressings are a combination of absorbent and elastomeric components that interact with wound fluid to form a gel. Some dressings have an adhesive layer of hydrocolloid that contacts the wound and a outer occlusive polyurethane film. The hydrocolloid adheres to the periwound skin, and the dressing over the wound interacts with wound fluid to produce an occlusive gel. The gel may have a mild odor and yellow purulent appearance. However, this should not be interpreted as inf...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Veterinary Wound Management Society Mission

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Basics of Bandaging, Casting, and Splinting

- 2 Head and Ear Bandages

- 3 Thoracic, Abdominal, and Pelvic Bandages

- 4 Extremity Bandages, Casts, and Splints

- 5 Restraint

- Suggested Reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Small Animal Bandaging, Casting, and Splinting Techniques by Steven F. Swaim,Walter C. Renberg,Kathy M. Shike in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Veterinary Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.