eBook - ePub

A Companion to Latin American History

Thomas H. Holloway, Thomas H. Holloway

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Companion to Latin American History

Thomas H. Holloway, Thomas H. Holloway

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Companion to Latin American History collects the work of leading experts in the field to create a single-source overview of the diverse history and current trends in the study of Latin America.

- Presents a state-of-the-art overview of the history of Latin America

- Written by the top international experts in the field

- 28 chapters come together as a superlative single source of information for scholars and students

- Recognizes the breadth and diversity of Latin American history by providing systematic chronological and geographical coverage

- Covers both historical trends and new areas of interest

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A Companion to Latin American History by Thomas H. Holloway, Thomas H. Holloway in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Latin American & Caribbean History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

EARLY POPULATION FLOWS IN THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE

Setting the Stage

The early history of human exploration and achievement in the Americas is a register of ideas inferred from the combination of archeological, paleoecological, biological, and linguistic data. Scholars have recognized many patterns in the data and proposed several interpretative scenarios, at local and continental scales, and their recurrence in time and space. These scenarios have emphasized the variable biological, social, and cultural capacities of the first humans to spread throughout the New World and their adaptations to changing environmental circumstances and their symbolic and material expressions. These adaptations across the Americas involved many cultural continuities and changes through the selective invention and exchange of cultural elements (Dillehay 2000; Adovasio & Page 2002; Meltzer 2003b).

The focus here is the first few millennia or so of human settlement in the New World, spanning the late Pleistocene and early Holocene period, from approximately 15,000 to 9,000 years ago, with implications for later periods. This coverage does not terminate the late Pleistocene at the usual arbitrary cut-off point of 10,000 years ago when deglaciation ended in most regions. That date prevents the late Pleistocene period from being considered as part of the social and cultural contributions made to later prehistory. In the pages that follow, the scholarly ideas and scientific evidence about this period are summarized, illustrating how our knowledge of the first Americans continues to develop. Although I primarily emphasize the technologies and economies of the first Americans, I also attempt to address social and other issues in hopes of imbricating the deep past with more recent indigenous cultural transformations.

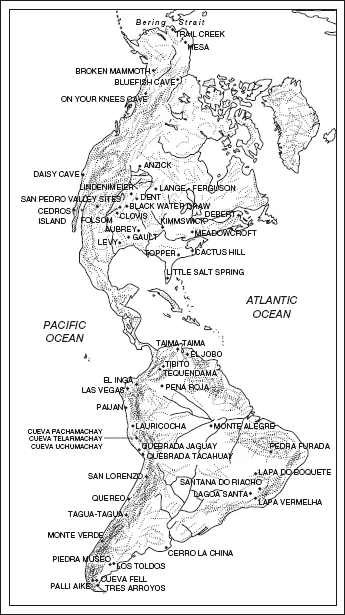

Much rethinking about the peopling of the Americas has occurred in recent years as a result of new discoveries in archaeology and paleoanthropology. Several archeological sites in both North and South America have much potential to document earlier traces of human occupation (Dixon 1999; Dillehay 2000; Meltzer 2003b). The eastern woodlands of the United States in particular have yielded more convincing evidence of sites ancestral to the widely documented 11,300-year-old Clovis culture, which is best known for its fluted bifacial projectile point and big game hunting tradition. Meadowcroft Shelter in Pennsylvania, Cactus Hill in Virginia,

Topper Site in South Carolina, and others suggest that groups of generalized hunters and gatherers may have lived in those areas as far back as 16,000 to 13,000 years ago (Figure 1.1) These possibilities are supportive of the 12,500-year occupation at Monte Verde and slightly later sites in South America, because if people first came into the New World across the Bering land bridge, we would expect earlier dates in North America. It also is likely that multiple early migrations took place and people moved along the edge of the ice sheets from Siberia to Chile (Fladmark 1979; Dixon 1999; Dillehay 2000) and possibly from northern Europe into eastern North America (Stanford and Bradley 2002). Recently, there is renewed discussion of possible influences from Australia and Oceania and even Africa. Some paleoanthropologists, led by the Brazilian Walter Neves (Neves et al. 2003), suggest that the oldest skeletal material from eastern Brazil more strongly affiliates with ancient Africans and Australians than with modern Asians and Native Americans. This suggests the presence of non-Mongoloid as well as Mongoloid populations in the Americas (cf. Steele & Powell 2002). Neves does not believe that these migrants came directly from Africa or Australia, but that they splintered off from an earlier group that moved through Asia and eventually arrived in Australia and America.

Figure 1.1 Location of major archeological sites of the late Pleistocene period in the New World

Linguists and geneticists also postulate earlier and multiple migrations. Johanna Nichols (2002) believes that a high diversity of languages among Native Americans could only have developed from an earlier human presence in the New World, perhaps as old as 30,000 to 20,000 years ago. Several geneticists present a similar argument derived from genetic diversity (e.g., Schurr 2004). Based on comparisons between certain genetic signatures shared by modern Native Americans and modern Siberians, it has been estimated that people from Siberia entered the New World at least 20,000 to 14,000 years ago. These first immigrants are believed to have followed a Pacific coastal route into the Americas, where they spread into all interior regions. Later interior migrations possibly moved into North and Central America where they mixed with earlier populations.

These new discoveries and ideas are not without their critics. Advent Clovis proponents who defend the Clovis-first theory still hold to the notion that the first Americans were mainly big game hunters who entered the Americas from Siberia no earlier than 12,000 to 11,500 years ago and spread rapidly throughout the Americas. These proponents believe that notions of a pre-Clovis presence at earlier sites are based on questionable radiocarbon dates, site stratigraphies, and interpretations of the evidence. Although these criticisms are often constructive and warranted for some earlier and often outlandish claims and encourage a more rigorous approach to the study of the first Americans, they are usually based on anecdotal tales, emotive vindication, and little scientific evidence.

The Pre-Clovis and Clovis Dilemma

In the 1950s, the discovery of fluted projectile points at Blackwater Draw, near Clovis, New Mexico, the type site of the Clovis culture, set the standard by which all other point types and early cultures would be measured for the next 50 years. Based on the later discoveries of more Clovis points at sites throughout North America, the Clovis culture came to be known as the first “migratory culture” in the

Americas. In essence, the Clovis point was equated with the first Americans and with early human migration from Siberia to Tierra del Fuego. The argument for the Clovis-first model has been based primarily on the stylistic association of a few similar traits such as fluting on lanceolate projectile points. Every time these and other traits have been found in the Americas, they have been uncritically interpreted as evidence of a Clovis culture and a Clovis migration. As a result, the Clovis culture has continually widened to include technologically distinct point types, such as the Fishtail, Restrepo, Paijan, and Ayampitin points in South America. None of these distinct types fit culturally, stylistically, and technologically with the Clovis point and with the Clovis-first scheme. It also remains unclear as to what Clovis culture is and the criteria employed to define it (cf. Haynes 1969; Dillehay 2000). Although there is a good understanding of Clovis stone tool technology, little still is known about the subsistence, social, domestic, and mobility patterns of regional Clovis cultures and even less about their possible relation to the early cultures and peoples of the Southern Hemisphere.

Despite the continuing debates over the first peopling of the Americas and the ambiguity and paucity of evidence, four issues are becoming clearer. Although Clovis culture is the most widely distributed early record in North America and accounts for a major portion of the first chapter of human history in the north, it fails to explain early cultural and biological diversity in all of the Western Hemisphere, especially in South America. Second, Northern Hemisphere agendas about the peopling of the New World, which were developed in the historically better investigated regions of North America, have created unrealistic expectations or preconceptions about the significance of cultural developments in South America. Despite the likely migration of early people from the north to the south, the archeological records of each continent must be viewed in their own terms and not be judged by preconceived notions usually based on meager evidence or overextended interpretative models (Dillehay 1999, 2000; Meltzer 2003). Third, many anthropologists now no longer consider the Clovis people to be purely big game hunters, but also small game hunters and gatherers of plants. And fourth, regardless of the quality of evidence, early American populations seem to present a cultural and biological melting pot for a long time and probably had their physical, genetic, and cultural roots in different areas. A lingering question is whether Clovis people developed from an earlier population in the Americas, or whether they were only some of the first Americans in some areas.

It is my belief that there were pre-Clovis populations in the New World sometime between 20,000 and 15,000 years ago. I also believe that the first migrants into the Americas adapted to many different environments quickly, creating a mosaic of contemporary different types of hunters and gatherers (i.e., big game hunters, generalized interior foragers, coastal foragers) immediately after they entered new environments. Further, in my opinion, a key issue is not rapid migration but rapid social change, cultural exchange, and a steep “learning curve” across newly encountered environments – adaptation of technological, socioeconomic, and cognitive processes over several generations (cf. Dillehay 1997, 2000; Meltzer 2003). As the early archeological records of South America and parts of the eastern United States suggest, this was not a single unitary process, but many. While different types of hunter and gatherer groups were settling into one new environment, others were probably just moving into neighboring areas for the first time. Others probably stayed for longer periodsin more productive environments. All of these processes must have begun sometime before 12,000 years ago in order to produce the types of technological and economic diversity reflected in the archeological record by 11,000 years ago in most regions of the Americas (Bryan 1973; Dillehay 1999, 2000). The record left behind by these processes is characterized by variable site sizes, locations, functions, occupations, artifact assemblages, and internal structures that reflect different adaptations to different environments and various degrees of social interaction between different populations.

Interdisciplinary Evidence and Words of Caution

It may be argued that one of the most direct evidences of humans in the Americas are the languages spoken by peoples of the hemisphere and the genetic linkages between them and others. However, there is no consensus among specialists as to the validity of historical linguistics and genetics in constructing models of American origins as far back as 10,000 years ago and more. Both historical linguistics and genetics can suggest likely places of origin of a language and genetic group, and the geography of its spread from such a point of origin, but on their own they cannot convincingly achieve a chronology for the spread of a language group or genetic population or the dating of a particular language stage and genetic mutation.

In regard to chronology, language and genetics do not change at a constant rate and we do know that language replacement can occur rapidly. What is required is a material indicator of the language spoken and of the genetic mixture to provide a correlation of language and date. As expected, such correlations are very difficult to find. These difficulties aside, it is important to consider the linguistic and genetic information for the Americas in relation to the archeological and biological evidence. The information gained from these disciplines enables the highlighting of the differences that exist between the current communities of the area, and warns of the complex associations between these communities in the present and the past. However, it must be kept in mind that it is difficult to associate historical linguistics directly with material evidence. And the genetic evidence must be derived from human skeletons. Further, both the linguistic and genetic chronologies must depend on radiocarbon and other dating techniques in archeology.

In this essay, I primarily consider archeology (including the scant skeletal material available for the late Pleistocene) to be the only reliable direct indicator of a human presence in the Americas, and the paleoenvironmental evidence, which may be used to provide a proxy (i.e., not direct) record of human presence. The environmental evidence, like the genetic and linguistic evidence, has problems related to its utility and interpretation. The archeological record also is problematic. It generally is not well preserved and often is disturbed by numerous natural processes that may destroy and mix evidence. Furthermore, early archeological sites are generally characterized by a narrow range of cultural materials and few internal site traits (e.g., hearths, activity areas). In fact, most early sites contain stone artifacts and, when preservation permits, the bone remains of animals. This forces archeologists to over-rely on technologically distinct and temporally sensitive stone projectile points, for example, in order to maximize information about the first Americans, which also is problematic.

To elaborate briefly, traditional approaches to the peopling of the Americas have relied too heavily on subjective aesthetic definitions of point styles (e.g., Clovis, Folsom, Fishtail, Paijan) from a wide variety of archeological sites in North and South America. Not yet fully integrated into these approaches are systematically contextualized archeological traits such as internal site patterning of non-projectile point stone tools, other artifacts and features (e.g., hearths, storage pits), and inter-site quantitative and qualitative comparisons between these and other variables. Point styles may be valid chronological and functional markers but not valid indicators of late Pleistocene social organizations, economic strategies, and patterns of early human entry and dispersion throughout the New World. Arguments for long-distance migration in the Americas must be founded on something more scientifically rigorous than a simple reference to the appearance of a single, possible foreign trait – that is, the flute on a Clovis point – and its possible association with a single similar trait elsewhere. A narrow focus on a single trait or small group of traits may conceal many other cultural possibilities. The lack of explicit study of a wide range of artifact sites and inter-site comparisons across the Americas impedes communication by restricting our understanding of what is meant by different artifact styles and their associated traits within and across different types of sites in different environments.

The New World during the Last Glacial Maximum

During the period 25,000 to 10,000 years ago shifting dry and hot or cold conditions prevailed over much of the hemisphere. This climatic regime peaked 21,000 to 15,000 years ago, during a period called the Last Maximum Glaciation, or LGM. Extensive areas of the northern half of North America and limited high-altitude and high-latitude areas of South America were glaciated during the LGM. During this period the sea level stood approximately 130 m below present level, so that the continents were larger than they are now. Much of the continental shelf that is now ocean floor was comprised of low-lying plains. Some would have been a continuation of dunefields and other geological formations, but others were resource-rich coastal lakes and lagoons, forests, and rugged hills, plateaus, canyons, and river valleys. Cooling of the ocean resulting from reduced glaciation decreased evaporation, and consequently throughout many regions precipitation was less.

Extensive dune whorls in the North American southwest and mid-Atlantic seaboard and in parts of northern South America dated to this period suggest a strong semi-permanent high-pressure system over many regions. The lack of warm sea in high-latitude areas and increasing land surfaces due to glacial retreat reduced the onshore movement of tropical rain depressions. Inland aridity was intense enough that lakes as far south as Chile and Argentina dried up, forests retreated, and some animals became extinct. Over the high-latitude regions severe cold, drought, and strong winds discouraged vegetation growth in some regions.

After the LGM world temperatures increased, the Northern and Southern Hemisphere icecaps began to shrink and as a response the level of the sea rose. A surge came at 15,000 years ago, when the North American ice sheets melted, but ice sheets in Antarctica began their retreat at 12,000 years ago. The land area shrank, and the present coastline began to form about 6,000 years ago. From 14,500 years ago, treelines climbed about 800 m in many areas, while glaciers and surrounding alpine and subalpine environments in the Rocky Mountains of North America and the Andean Mountains of South America retreated. This shift in the location of higher-altitude forests often restructured the diversity and type of resources available to people, especially in hilly and mountainous areas. In many areas, temperature increased by 5–6 C. In the interior of both North and South America, especially in the temperate woodlands of eastern North America and in the tropics of the Amazon Basin, there was sufficient humidity and cooler temperatures to sustain vegetation, and dune building decreased. Progressively, dunefields across the continent stabilized and forests replaced former shrubby grassland and savanna. From 11,500 years ago many plant species in mountainous environments migrated inland and to higher altitudes, replacing grasslands and savannas.

When people first arrived in the Americas and dispersed across the continents, they faced a continual series of environmental challenges that persisted throughout the late Pleistocene and early Holocene. The adaptability and endurance in colonizing the Americas produced early cultural diversity across these environments, including specialized big game hunters in open terrain such as the Great Plains in North America and the Pampa and Patagonian grasslands in Argentina and Chile, specialized maritime foragers along both the Pacific and Atlantic shorelines, and various kinds of generalized foragers in various parkland, savanna, and forest habitats.

Extinction of Megafauna

Most mammal species inhabiting the Americas in the late Pleistocene survived into modern times. Those that did not survive include most of the largest species. These extinctions occurred as mosaics of individual events in different parts of the Americas over many thousands of years. Late Pleistocene extinctions included mastodont, wooly mammoth, American horse, giant armadillo, ground sloth, ancient bison, and others. During the late Pleistocene nearly all animals had a larger body mass than their modern descendents. Many researchers believe that some of the large species did not become extinct at all, but simply became smaller because of a strong selective force for smaller body size as modern climatic conditions approached. Such a trend is particularly notable among the grazing animals.

There are different explanations for why so many animal species, especially the larger ones, became extinct within the last several millennia. The main arguments concern environmental changes of natural origin, and over-hunting. However, no single cause is sufficient to explain the disappearance of a large and diverse range of animals adapted to such a wide range of habitats. Least evident is the part humans may have played in the process. An extreme view of the human intervention explanation is the “blitzkrieg hypothesis,” formulated by Paul Martin (1984) to explain animal extinctions in North America. This argument is that the larger animal species were eliminated by “overkill” shortly after people first arrived in the continent. Other less extreme positions are that small-scale but continuous hunting of megafauna, or large-scale burning which changed the landscape, had cumulative long-term effects that threw megafauna into an irreversible decline. There also are multi-causal explanations that combine human intervention with climatic change, offering a scenario ofsustained hunting of species that were ecologically stressed by the onset of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures, Tables, and Maps

- Notes on the Contributors

- Introduction

- Chapter One: Early Population Flows in the Western Hemisphere

- Chapter Two: Mesoamerica

- Chapter Three: Tradition and Change in the Central Andes

- Chapter Four: Portuguese and Spaniards in the Age of European Expansion

- Chapter Five: Exploration and Conquest

- Chapter Six: Colonial Brazil (1500–1822)

- Chapter Seven: Institutions of the Spanish American Empire in the Hapsburg Era

- Chapter Eight: Indigenous Peoples in Colonial Spanish American Society

- Chapter Nine: Slavery in the Americas

- Chapter Ten: Religion, Society, and Culture in the Colonial Era

- Chapter Eleven: Imperial Rivalries and Reforms

- Chapter Twelve: The Process of Spanish American Independence

- Chapter Thirteen: New Nations and New Citizens: Political Culture in Nineteenth-century Mexico, Peru, and Argentina

- Chapter Fourteen: Imperial Brazil (1822–89)

- Chapter Fifteen: Abolition and Afro-Latin Americans

- Chapter Sixteen: Land, Labor, Production, and Trade: Nineteenth-Century Economic and Sociai Patterns

- Chapter Seventeen: Modernization and Industrialization

- Chapter Eighteen: Practical Sovereignty: The Caribbean Region and the Rise of US Empire

- Chapter Nineteen: The Mexican Revolution

- Chapter Twenty: Populism and Developmentalism

- Chapter Twenty-One: The Cuban Revolution

- Chapter Twenty-Two: The Market Revolution

- Chapter Twenty-Three: Central America in Upheaval

- Chapter Twenty-Four: Culture and Society: Latin America since 1900

- Chapter Twenty-Five: Environmental History of Modern Latin America

- Chapter Twenty-Six: Women, Gender, and Family in Latin America, 1820–2000

- Chapter Twenty-Seven: Identity, Ethnicity, and “Race”

- Chapter Twenty-Eight: Social and Economic Impact of Neoliberalism

- Index