- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This major new study by one of the most penetrating and persistent critics of philosophical and scientific orthodoxy, returns to Aristotle in order to examine the salient categories in terms of which we think about ourselves and our nature, and the distinctive forms of explanation we invoke to render ourselves intelligible to ourselves.

- The culmination of 40 years of thought on the philosophy of mind and the nature of the mankind

- Written by one of the world's leading philosophers, the co-author of the monumental 4 volume Analytical Commentary on the Philosophical Investigations (Blackwell Publishing, 1980-2004)

- Uses broad categories, such as substance, causation, agency and power to examine how we think about ourselves and our nature

- Platonic and Aristotelian conceptions of human nature are sketched and contrasted

- Individual chapters clarify and provide an historical overview of a specific concept, then link the concept to ideas contained in other chapters

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The Project

1. Human nature

Human beings are animals with a distinctive range of abilities. Though they have a mind, they are not identical with the mind they have. Though they have a body, they are not identical with the body they have. Nor is a human being a conjunction of a mind and a body that causally interact with each other. Like other animals, human beings have a brain on the normal functioning of which their powers depend. But a human person is not a brain enclosed in a skull. A mature human being is a self-conscious agent, with the ability to act, and to react in thought, feeling and deed, for reasons.

Animals, like inanimate objects, are spatio-temporal continuants. They have a physical location and trace a continuous spatio-temporal path through the world. In this sense, they are, like familiar material objects, bodies located on, and moving on, the face of the earth. They are substances, persistent individual things that are classifiable into various substantial kinds according to their nature and our interests. (What counts as such a classifying noun will be examined in chapter 2.) Animals are animate substances – living things. So, unlike mere material objects, they ingest matter from their environment and metabolize it in order to provide energy for their growth, their distinctive forms of activity, and their reproduction. Unlike plants, animals are sentient agents, and all but the lowliest forms of animal life are also self-moving. Their sentience is exhibited in their exercise of the sensefaculties they possess: for example, the perceptual faculties of sight, hearing, smell, taste and feeling, and in the actualization of their passive powers of sensation: for example, susceptibility to pain, kinaesthetic sensation and liability to overall bodily feelings, such as feeling tired, and feelings of overall condition, such as feeling well. The perceptual faculties are cognitive. They are sources of knowledge about the perceptible environment. It is by the exercise of these sense-faculties, by the use of the sense-organs that are their vehicles, that animals learn about the objects in, and features of, their environment. Being sentient and being self-moving are complementary powers of animal agency. For an animal that can learn how things are in its vicinity exhibits what it has apprehended both in its finding the things it seeks (such as food, protective environment, a mate) and in its avoiding obstacles and dangers. The criteria for whether an animal has perceived something lie in its responsive behaviour – so perception, knowledge and belief, affection, desire and action are conceptually linked.

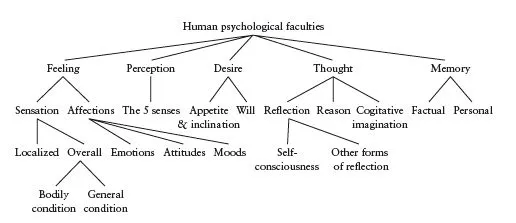

The abilities distinctive of human beings are abilities of intellect and will. The relevant abilities of intellect are thought, imagination (the cogitative and creative imagination rather than the image-generating faculty), personal (experiential) and factual memory, reasoning and selfconsciousness. Human beings have the ability to think of (and imagine) things that lie beyond their present perceptual field – to think of things as encountered in the past and of the encountering of them, of past things learnt about and of the learning of them, of future things that do not yet exist and of eventualities and actions that have not yet occurred or been performed. To the extent that other higher animals possess comparable abilities, then they do so only in rudimentary (prelinguistic) forms. Humans can think both of what does and also of what does not exist or occur, of what has or has not been done, and of what will and what will not be done. We can believe, imagine, hope or fear that such-and-such is the case, irrespective of whether things are so or not. In short, thought, both in rudimentary form in animals and in developed form in humans, displays intentionality. Not only can we think of and about such things, and think that things are thus-and-so, but we can reason from such premisses to conclusions that follow from or are well supported by them. And we can evaluate such reasoning as valid or invalid, plausible or implausible. Because the horizon of human thinking is so much wider than that of non-human animal thinking, so too the horizon of human feelings and emotions is far wider than that of other animals. Both humans and animals can hope and fear things, but many of the things that humans can hope for (such as salvation, or good weather next week) and fear (such as damnation, or bad weather next week) are not possible objects of corresponding animal emotions.

Like other animals, we are conscious creatures. When conscious (as opposed to being asleep, comatose or anaesthetized), we may be conscious of those items in our perceptual field that catch and hold our attention. Unlike other animals, we are also self-conscious. We have not only the power to move at will and to perceive how things are in our environment, but also the power to be reflectively aware of our doing or having done so. We can not only think and reason, but can further reflect on ourselves as having thought or reasoned thus-and-so. We can not only have reasoned desires in addition to animal appetites, feel emotions and adopt attitudes, deliberate upon goals and purposes, but we can also realize and reflect on such facts. Being self-conscious creatures, we are subject to a variety of emotions of self-assessment, such as pride, shame and guilt, that are foreclosed to non-self-conscious animals (see fig. 1.1).

Figure 1.1. A possible ordering of human psychological faculties

Human beings can reason from given premisses to theoretical or practical conclusions. We can take such-and-such to be a reason for thinking that things are thus-and-so. We can also take things’ being thus-and-so to be a reason for acting or reacting in a certain way. For we do not merely behave and act as our appetites and fancies incline us, we do much of what we do for reasons. We have not only animal desires and passing inclinations, we also have reasoned goals and purposes rooted not merely in our biological make-up, but in reflection on the desirability of objects and objectives relative to our conception of our good and of the good. Rationality is Janus-faced, incorporating both backward- and forward-looking reasons. Inasmuch as we possess an articulate memory, we can take past facts as reasons for present actions and attitudes – as when we act out of gratitude, punish or reward desert, harbour indignation or resentment, or feel ashamed or guilty. Because we can think about and come to know truths or probabilities concerning the future, we can take future facts or the likelihood of future eventualities as reasons for us to act in certain ways here and now. Our behaviour can accordingly be evaluated as rational or reasonable, as well as irrational or unreasonable. And so too can our emotions and attitudes.

These capacities and their exercise give to human beings the status of persons. While human being is a biological category, person is a moral, legal and social one. To be a person is, among other things, to be a subject of moral rights and duties. It is to be not only an agent, like other animals, but also a moral agent, standing in reciprocal moral relations to others, with a capacity to know and to do good and evil. Since moral agents can act for reasons, and can justify their actions by reference to their reasons, they are also answerable for their deeds. To be a human being is to be a creature whose nature it is to acquire such capacities in the course of normal maturation in a community of like-natured beings.

2. Philosophical anthropology

The above thumbnail sketch in one sense locates human nature in the scheme of things – but the scheme in which it locates it is our conceptual scheme. So much of the sketch is also an indirect description of the network of concepts in terms of which we articulate our nature. It locates the forms of description of human nature in the general conceptual scheme in terms of which we describe all else. The methodical description of the structure of this finely woven network and the examination of some of the ways in which it has been and is commonly misconstrued is the objective of the following studies in philosophical anthropology. This term of art has a wider scope than ‘philosophy of mind’ or ‘philosophical psychology’, although, as I shall use it, it incorporates these. Philosophical anthropology is the investigation of the concepts and forms of explanation characteristic of the study of man. The systematic description of this network of concepts will enable us to shed light on a multitude of philosophical problems and controversies about human nature and the forms of explanation of human behaviour. Prior to commencing the present task, some methodological reflections are necessary to characterize the task and to defend the methods that will be used.

It would be misguided to suppose that the concepts invoked and their complex relationships are the concepts and conceptual network of a theory of some kind (sometimes referred to contemptuously as ‘folk psychology’) that might be abandoned if the theory were found defective. Theoretical concepts can indeed be jettisoned with the theory to which they belong, if the theory is radically awry. The concepts of phlogiston and caloric are now of mere historical interest. Non-theoretical concepts include the numerous concepts that are employed, inter alia, merely to describe phenomena. The phenomena thus described may or may not stand in need of explanation. In some cases, the explanation needed may be theoretical; but not all explanation is theoretical. Non-theoretical concepts do not fall victim to the falsity of an explanation or falsification of an explanatory theory.

The concepts of a human being, of a person, of the mind and body of a person, of the intellect and the will, perception and sensation, knowledge and belief, memory and imagination, thought and reason, desire, intention and will, feelings and emotions, character traits and attitudes, virtues and vices, are not theoretical concepts. They are not concepts that we could abandon after the manner of phlogiston or caloric. They are used, a-theoretically, to describe phenomena that are the subject matter of numerous theories in the study of human beings, in psychology, anthropology, sociology, history and economics. But that is not their sole role.

These anthropological and psychological concepts do not stand to what they can be used to describe merely as representation to what is represented. For our use of many of these concepts and their congeners itself moulds our nature as human beings, as conceptemploying, self-conscious creatures. So their use is partly constitutive of what they can also be invoked to describe. The availability of these concepts gives shape to our subjective experience, for it is by their use, in the first person, that we are able to give it articulate expression.

In learning the vocabulary of psychological concepts, a child is not learning a theory of anything. He is, on the one hand, learning new forms of behaviour – learning to replace his cries of pain by ‘It hurts’ or ‘I have a pain’ and his cries of indignation with ‘No!’ and ‘I don’t like it’; to herald his deliberate actions by ‘I’m going to’ and later his plans by ‘I intend’, to prefix an ‘I think’ to, or interpolate an ‘I believe’ or an ‘as far as I know’ in, his unconfirmed assertions; and to preface his fearful but false descriptions on waking from a nightmare with ‘I dreamt’. On the other hand, he is learning to describe other people and to describe and explain their behaviour in these terms. But there is nothing theoretical about describing others as being in pain, listening to this or smelling that, wanting this and thinking that, intending, liking, loving and so forth. The mental is not hidden behind behaviour; but, one might say, metaphorically speaking, that it infuses it. We must not confuse the possibility of not exhibiting or expressing it, or of suppressing its manifestation and concealing it, with the idea that it is unobservable by others. To be sure, this is not to endorse any form of behaviourism. It is often possible not to show that one has a headache; but when one is injured and writhing in agony, one’s pain is patent. That is what is called ‘showing one’s pain’. One can think something to be the case, and not say what one thinks; and it is often possible to keep one’s thoughts to oneself. But when one says what one thinks, one’s thoughts are patent, and when one sincerely confesses one’s thoughts to another, one’s thoughts are laid bare. Nor should we suppose that the mental is observable by the subject, as if one enjoyed privileged access to one’s ‘domain of consciousness’. There is such a thing as introspection, but it is not a kind of inner perception – it is a form of self-reflection. Such confusions and suppositions concerning psychological concepts incorporate deep and ramifying errors which infect empirical sciences of man, such as psychology and cognitive neuroscience.

Furthermore, the characteristic forms of explanation of human behaviour in terms of reasons are not to be found in the natural sciences and are not proto-scientific explanations. Teleology is, to be sure, also appropriately invoked in the study of non-human, biological phenomena. So too are the concepts of goal, purpose and function. But explanation in terms of reasons and motives is distinctive of human behaviour. This too is not part of a proto-science, although it is true that these forms of explanation characterize the study of man in history, psychology and the social sciences. But, like the psychological and anthropological concepts that are involved in such explanations, the explanations themselves are typically partly constitutive of the phenomena that they explain. To learn, as every human being does, to give such explanations at the homely level of personal action and relations is not to learn the rudiments of a science. It is to learn to be a rational human being and to participate in the human form of life that is the birthright and burden of the children of Adam.

3. Grammatical investigation

So, the theme of the following philosophical investigations is human nature. But it is simultaneously the grammar of the description of what is distinctively human. And it is the former because it is the latter. For the investigations are purely conceptual. They explore the concepts and conceptual forms we employ in our thought and talk about ourselves, and examine the logico-grammatical relationships between these concepts and conceptual forms.

The study of the nature of things, in one sense, belongs to the empirical sciences. It is the task of physics, chemistry and biology, of psychology, economics and sociology to discover the properties and relations, the regularities and laws, of the objects that fall within their domain. Empirical observation leads to explanatory theory, commonly with predictive and retrodictive power. Theories involve abstraction and generalization from observed data, and the confirmation or infirmation of conjectures in experience. The truths discovered are empirical truths, and the theories confirmed are empirical theories.

The study of the nature of things, in another sense, belongs to philosophy. This investigation has sometimes been characterized as the quest for the essential nature of things, and contrasted with the empirical sciences that are conceived to study their contingent nature. In past ages such investigation was allocated to the Queen of the Sciences – metaphysics. The de re essences of things provided the subject matter of metaphysical philosophy, and their disclosure its sublime task.1 This, however, was an illusion. There is no such thing as metaphysics thus conceived, and no such subject matter for philosophy to investigate.

It is one thing to grant that substances of a given kind have essential as well as accidental properties, or that the instantiation of certain properties or relations entails the instantiation or exclusion of certain other properties and relations. It is quite another to hold that propositions that state the essential properties of a given substance or the relations of inclusion or exclusion that hold between properties and relations describe mind-independent, language-independent, metaphysical necessities in reality. What appear here to be descriptions of de re necessities are actually norms of representation. That is, they are not descriptions of how things are, but implicit prescriptions (rules) for describing how things are. Consider the following four propositions:

(i) A material object is a three-dimensional space-occupying entity that can be in motion or at rest and consists of matter of one kind or another.

(ii) Every event is temporally related to every other event.

(iii) Nothing can simultaneously be red all over and also green all over.

(iv) Every rod has a length.

Such propositions appear to be descriptions. They are what we think of as necessary truths, for, to be sure, nothing can be a material object that is not a space-occupant or that does not consist of material stuff; it is inconceivable that there be an event that is neither earlier nor later nor yet simultaneous with, or a constituent phase of, any other event, or that something be both red all over and green all over simultaneously; and it is not a contingent matter that we shall never find a rod without a length.

Appearances are deceptive. These sentences express rules for the use of their constituent terms in the guise of descriptions. If we characterize something as a material object, then it follows without more ado that we may characterize it as a space-occupant made of matter of some kind. We do not have to check to see whether perhaps this material object is not made of some matter or other, or whether it may have no spatial location. These internal (defining) properties and relations are constitutive of what it is to be a material thing: they are part of what we mean by ‘material object’. If reference is made to some event, we can infer without more ado that it is either earlier than, later than, simultaneous with, or a constitutive phase of any other event. If something is described as being red all over, it follows that it is not also green all over – this is not something that we need to confirm by looking. And if something is said to be a rod, it follows that it can be described as having a certain length. What appear to be descriptions of meta-physical necessities in nature are norms (rules) for describing natural phenomena. We would not call something a material object if it occupied no space or did not consist of matter; we would not deem something to be a genuine event if it were not simultaneous with, earlier or later than, or a phase of, any other given event; we would not describe something as being red all over if we were willing to describe it as green all over; and we would not hold something that lacked a length to be a rod. These are not discoveries about things, but the commitments consequent on employing a certain form of representation or description.

While the truth of an empirical proposition excludes a possibility, the truth of such necessitarian propositions as that nothing can be red and green all over, or that there cannot be a rod without a length, or that every material object must be located somewhere, somewhen, does not. A logical or conceptual i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series

- Title page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- 1: The Project

- 2: Substance

- 3: Causation

- 4: Powers

- 5: Agency

- 6: Teleology and Teleological Explanation

- 7: Reasons and Explanation of Human Action

- 8: The Mind

- 9: The Self and the Body

- 10: The Person

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Human Nature by P. M. S. Hacker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.