eBook - ePub

Wiring the Brain for Reading

Brain-Based Strategies for Teaching Literacy

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Using the latest neuroscience research to enhance literacy instruction

Wiring the Brain for Reading introduces teachers to aspects of the brain's functions that are essential to language and reading development. Marilee Sprenger, a specialist in learning and the brain, provides practical, brain friendly, strategies for teaching essential skills like phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. The author's innovative approach aligns well with the Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts and is designed to enhance students' motivation and excitement in reading.

- Offers a clear explanation of brain functioning in order to enhance language and reading instruction

- Incorporates proven literacy strategies, games, and activities as well as classroom examples

- Aligns with Common Core State Standards for learning to read, developing fluency, and interpreting complex texts

Wiring the Brain for Reading offers practical strategies for applying the latest research in neuroscience and learning to the classroom.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Wiring the Brain for Reading by Marilee B. Sprenger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Teaching Methods for Reading. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Language Development

Maeve was born already recognizing the voices of her mother and father. She had been able to hear her mother while in the womb as soon as her ability to hear sound developed by the end of the second trimester of the pregnancy. Soon after, as Maeve's daddy started reading to her and speaking to her in his soothing voice while keeping his mouth close to her mother's belly, she began to respond to the sound of his voice. The clarity of such verbiage to the unborn child has been questioned. But the moment Maeve was born, she responded and turned toward the voices of both Mommy and Daddy.

Maeve's brain at birth will allow her to learn any language and repeat any phonemes (the individual sounds that make up a language) that she hears. If she has been born into a bilingual or multilingual family, she will easily learn the languages that are spoken to her. This ability is short-lived, however. By the time Maeve has been on Earth a year, her brain will have pruned away the neurons (the brain cells that do the learning) that were not used. In other words, her ability to hear some phonemes will be gone or at least partially diminished. She will focus on the sounds that she hears, and by approximately eight months of age, she will begin to attempt to mimic those sounds. Along with the vowels and consonants she will mimic, she may also express other phonemes that are available to her developing brain. Her parents, however, will recognize only the sounds that they know. So when Maeve begins to babble a string of sounds like, “ma, ba, goo, eh, neh, un,” what her parents pick up on (especially Mom) is the first sound, “ma.” So Mom begins to repeat the sound while she beams at Maeve. “Ma, ma, ma … you said my name: ma, ma, ma.” Eventually Maeve gets the idea that this particular sound gets a great response from her mother, and she will begin to repeat the sound to please her mother and get instant feedback. It doesn't matter that within her babbling, she may have shared phonemes from multiple other languages. Since no one will repeat these back to her, she won't strengthen the connections for those sounds. As language is learned, brain cells connect to remember and recreate the sounds that are heard, but connections that are not used often grow weak and unusable.

There are almost seven thousand languages in the world, and babies are born with the ability to master any of them. But the brain changes as children develop, and language acquisition can become more difficult. In order to be able to read, a child must first learn the sounds of the language.

From Neural Sensitivity to Neural Commitment

After an infant is six to nine months of age, only those neurons that have learned the sounds of the language's phonemes spoken to the baby remain. They gain in strength and connections as they are repeated. As this specialization occurs, neurons become committed to those sounds (Bronson & Merryman, 2009).

In 2007, a study by Zimmerman, Dimitri, and Meltzoff stated that DVDs and videos directed to babies are actually harmful to them. The researchers had found that infants who watched these DVDs and videos had smaller vocabularies than babies who did not watch. In fact, the more television a child watched, the fewer vocabulary words he or she knew. The authors of the study gave possible reasons for the vocabulary differences they found:

- Some parents put their children in front of the television for up to twenty hours per week. They thought watching this material would help with brain development, but in fact it meant less time that the babies spent with people talking directly to them.

- Learning speech is partially a process of reading lips. Babies need to see people speaking in order to learn how to move their mouths and lips. Many baby DVDs instead show abstract pictures with voices talking about them.

- It is not possible to segment sounds in speech without seeing people speaking.

- These videos and DVDs lacked the visual and auditory components of speech interaction that are appealing to babies, that is, a face and voice to perform for and respond to.

Videos and DVDs could be made for infants with people speaking directly to the screen, and that might make a little difference. However, this would still leave out the most important component of learning to speak: human interaction.

A recent study published in the Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences suggests that babies lip-read as they learn language (Lewkowicz & Hansen-Tift, 2012). The study, from Florida Atlantic University, was conducted using 179 babies aged four, six, ten, and twelve months from English-speaking families. The study stated that the four-month-olds looked at the eyes of the speaker, but as the children got closer to beginning to babble, their gaze shifted from eyes to mouth. By six months of age, the babies spent half of their time looking at the eyes of the speaker and the remaining time at their lips. The eight- and ten-month-old babies spent most of their time watching the mouth of the speaker. As the babies prepared to begin speaking, most at the age of twelve months, their gaze shifted back to eyes. Confirming the need for lip reading was accomplished by having these babies watch a Spanish speaker. Again the eyes shifted to the mouth so babies could see how the sounds were formed.

Nature Versus Nurture

Are children born with an innate ability to speak, or is it their experiences and their environment that pave the way for language? Although the brain was once described as a tabula rasa, a blank slate, many researchers believe that the answer lies somewhere in between a blank slate and a preprogrammed mind.

Although children are born with the ability to learn speech, language learning does not occur in a vacuum. Babies don't begin speaking a language that they have never heard. Little Maeve will learn to speak English because her parents and others in her environment speak only English. If Maeve's Russian grandmother lived in the home and spoke only Russian, Maeve would easily pick up that language, too.

When Maeve begins to babble, she will make sounds that imitate the phonemes that she has been exposed to and also some sounds from other languages that she has not heard. She will simply be producing whatever sounds she can. Once she becomes more aware of her own language, she will repeat the sounds that she hears.

The Right Way to Babble

It may be hard to believe that babbling has been researched, but the University of Memphis has researchers who have done just that. Analyzing the sounds that babies make beginning at birth (Oller, 2010) has uncovered some interesting milestones in the process of learning language.

Babbling is an element of brain development in both social and emotional areas as well as cognitive development. It represents the learning that is taking place in relationship to language, and it is also an attempt to communicate and interact with the caregiver. A baby who isn't babbling in a typical way may have problems hearing or processing sounds, or perhaps the baby's brain is not being introduced to enough words.

According to pediatrician Perri Klass, babies babble in all of the world's languages. It is a universal sign of neurological development and an indicator of speech readiness. From babbling, infants and toddlers move on to making the sounds of their language and create words appropriate to their environments.

If a baby is not making those combined consonant vowel sounds, there may be a problem. By seven months (remember that development can vary among babies), if the baby is making only vowel sounds, the baby is not getting the practice she needs to begin to form words. Her mouth and tongue are not working the muscles necessary for good speech either (Stoel-Gammon, 2001).

Babbling may be a signal that babies are focused for learning, indicating an opportunity to have the baby's attention as he explores the world and wants to name the objects and people around him.

Encouraging Speech

Parenting experts offer some of the following suggestions for encouraging babies to use their language:

- Talk a lot. Between birth and three months, babies begin to acquire language, even though they cannot yet speak, so parents and caregivers are encouraged to talk to babies often.

- Point out things. As you talk to the infant, name items and describe what is going on.

- Help the infant listen. Point out the sounds around him: “Do you hear the clock?” “Is the dog barking?”

- Play games. The rhythm, rhyme, and play of games such as “Peek-a-boo” and “Pat-a-Cake” show the child that language is fun.

Studies have shown that babies whose mothers talk a lot have larger vocabularies than those whose mothers talk very little. It is possible, however, to take talking to the baby too far. Talking at a baby nonstop is not what promotes good language. Asking questions and responding to what the child says are also important.

The most famous study of children and language was carried out by Betty Hart and Todd Risley from the University of Kansas. Although an older study (1995), it is often still considered the gold standard when it comes to determining language development in children. In this groundbreaking work, researchers went into the homes of families of varying socioeconomic status and videotaped the parents as they interacted with their babies, who were between seven and nine months old at the beginning of the study. The taping was done once a month until the children were three years old.

In their book Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experiences of Young American Children (1995), Hart and Risley state, “By age 3 the children in professional families would have heard more than 30 million words, the children in working class families 20 million, and the children in welfare families 10 million” (p. 132). Although the number of words spoken was different, the style of speech and the topics were similar. The more the parents spoke, however, the more likely they were to ask the child questions and the more varied the vocabulary became, so the children received more experience with different language qualities.

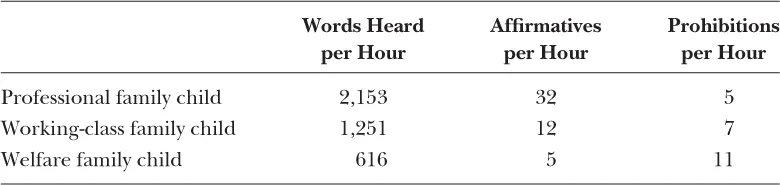

In addition to counting the number of words that parents spoke to the children, Hart and Risley also examined the types of reinforcement the children received. Table 1.1 shows the number of affirmative statements versus prohibitory statements tallied for each socioeconomic group. An example of an affirmation is “Nice job. You are doing a great job!” A prohibition may be something like “Don't do it that way. Can't you do anything right?” The professional parents offered affirmative feedback much more often (every other minute) than the other groups, and the welfare parents gave their children more than twice as many prohibitions as the professional parents.

Table 1.1 Affirmatives and Prohibitions Given per Hour

Some children in professional families heard 450 different words and 210 questions in the three hours in which the parent spoke most. Another child in that same amount of time heard fewer than 200 different words and 38 questions. The results of the study led all to believe that the most important component of child care is the amount of talking occurring between child and caregiver.

But perhaps they were wrong. Newer research by Catherine Tamis-LeMonda of New York University and Marc Bornstein of the National Institutes of Health lead us down a slightly different path. When comparing maternal responsiveness in children who came from professional families, they found some surprises. The study found that the average child spoke his or her first words by thirteen months and by eighteen months had a vocabulary of about fifty words. However, mothers who were considered high responders, that is, they responded to their child's speech quickly and often, had children who were clearly six months ahead of the children whose mothers were low responders. These toddlers spoke their first words at ten months, had extensive vocabularies, and could speak in short sentences by fourteen months (Bronson & Merryman, 2009).

This response pattern sent specific messages to the brains of the toddlers. The first message is that what they are saying makes a difference and causes ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Dedication

- About the Author

- About the Book

- Chapter 1: Language Development

- Chapter 2: Imaging and Imagining the Brain

- Chapter 3: The Body-Brain Connection

- Chapter 4: Breaking the Code

- Chapter 5: Patterns and Programs and Phonics! Oh, My!

- Chapter 6: The Fluent Reader

- Chapter 7: Building Vocabulary

- Chapter 8: Comprehension: Reading It and Getting It

- Chapter 9: Putting It All Together

- References

- Index