![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

1.1 Knowledge in Landscape Architecture

The “new normal” in landscape architecture is the production and consumption of knowledge. The past two decades have seen an unprecedented increase in the standards and complexity of disciplinary expertise, and with that comes increasing pressure to formalize the ways in which we seek, create, and validate knowledge. As the discipline expands and engages with other disciplines to address the profound challenges of the twenty-first century, there is pressure to include a broader base of thinking in the field and to deepen the way we think. These dynamics intersect in research.

This book offers researchers in landscape architecture a place to begin shaping their research program. It comprises a critical review of research strategies that have built and continue to build the knowledge base in landscape architecture. Its primary audience is students in higher education who are working on capstone or terminal studio projects, advanced independent studies, theses, or dissertations, as well as faculty who are supervising graduate students. As the number and size of Master of Landscape Architecture (MLA) thesis and PhD programs expand (Tai 2003), candidates and examiners require guidance and clarity of expectations about acceptable research methodology—that is, the principles, practices, and procedures of inquiry that characterize the discipline.

The career development and eventual success of academic staff also hinges increasingly upon their research agenda: its productivity, value, and impact. Universities and funding agencies demand metrics of performance and productivity that indicate the quantity and quality of research activity and dissemination, and programs are frequently ranked on this basis. In some countries, public funding for universities is tied directly to research output (Forsyth 2008), and there may be financial incentives that favor postgraduate education that involves substantial research outcomes. All of these activities involve creation of new knowledge, for which a clear strategy, or systematic process of inquiry, is needed.

An important secondary audience for the book is landscape practitioners in private-sector design, multidisciplinary or corporate consulting firms, public-sector agencies, and academia. In the design and development industry, as well as in government sectors and at not-for-profit agencies, research is becoming integral to shaping policy and practice. Indeed, success in business often depends on developing strategies for innovation in order to maintain competitiveness. “Evidence-based design” (Davies et al. 2000) is an area of fast-growing interest, as clients, public officials, and practitioners seek credible sources of knowledge of landscape and social processes upon which to base their evaluation of design proposals and policy recommendations. Forms of peer review are increasingly used in all of these situations, but they still beg the questions of which research strategies are effective and appropriate for the discipline and by what criteria should new knowledge be evaluated.

1.2 The Need for a Guide

There is at present little disciplinary guidance on research strategies. Nor is there any clear standard within landscape architecture for courses in research design and methods that are required in graduate design programs and, increasingly, taught to undergraduates. Rather than teaching from a broader “meta,” or strategic, perspective, faculty members often teach research design in a way that reflects their own familiarity with a single research method or a category of methods (e.g., survey or thematic maps). Their task is made even more difficult because no single text adequately serves the landscape architecture student in finding his or her own focus of inquiry or allows the student to position his or her work in the context of a larger investigative framework. The problem is confirmed regularly in informal and formal discussions at educators’ conferences in North America, Europe, and Pacific Rim countries, and we have repeatedly encountered this need in our own teaching.

Equally, there are no discipline-wide protocols or frameworks in landscape architecture by which to evaluate the validity of research proposals that seek commercial or public funding, or to assess the claims made by practitioners in the explanations of their projects, in competition entries, and in their written work. Clients in the public sector have no basis upon which to judge the validity of assumptions and presumptions made as a basis for policy advice.

This book aims to empower and inform new researchers, evaluators, and clients of research and theoretically justified work by providing a framework through which to address the following questions:

1. What research strategies are possible in landscape architecture?

2. What strategies do landscape architectural researchers tend to use?

3. How might an effective research strategy be shaped, and how might it be evaluated?

It follows that we focus primarily upon strategies rather than methods—on the configuration of an overall system of inquiry relative to the current range of epistemological and theoretical perspectives in our field, rather than upon detailed procedures, methods, and techniques that may be relevant to a particular investigation. This reflects our belief that, rather than method, it is the perspective driving an inquiry that is most fundamental in shaping any research project, and that it is the application of distinctive inquisitive strategies within particular theoretical contexts that shapes a discipline. Many methods and techniques are interchangeable across disciplines. It is the way they are used, combined, and linked to theoretical propositions and practical actions in a coherent overarching strategy that gives them a distinctive disciplinary character.

It is also important to dispel any potential confusion in the overlapping concepts of research design and research strategy. In this book, research design refers to the logical order or structural composition of an investigation; essentially it is a formal, or a formulaic protocol. Trochim (2006) calls research design “the glue” that keeps a research project together. Many sources suggest that there are only a limited number of possible research designs (e.g., randomized experiment, quasi experiment, nonexperiment). Research design guides the way in which an inquiry selects from and processes all possible sources of data (i.e., sampling approach) and treatments.

Research strategy, on the other hand, is essentially conceptual and is shaped by intention—not by the “how,” but by the “why” of finding out. The nature of any research strategy is defined by two key dimensions that guide the process of scholarly inquiry. The first is the purpose or the relationship of the inquiry to theory—is the purpose of the investigation to build, shape, or test theory? The second dimension is the nature of the truth claims, or epistemology, that lie behind the investigation—is reality dependent upon, independent of, or interdependent between the researcher and the world?

Hence, research strategy is clearly related to, but larger and more conceptual than, research design. Research strategy subsumes research design within a larger order or agenda of thought and action. Research design is the investigative structure or logic created in the service of particular intellectual strategies; research methods are specific procedures used to advance particular research designs; research techniques are used to access and organize data (e.g., interviews) in support of particular methods.

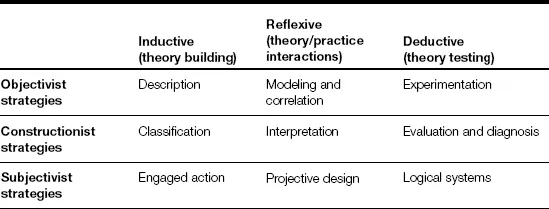

In essence, the “strategies” that we present in this text are methodologies (studies of multiple methods) that are organized by and instrumental to an intellectual purpose and epistemological position. This guides their placement in a classification matrix (see Section 1.4). One order below that, our examples describe specific research designs, research methods, and analytical techniques that illustrate how these strategies operate in support of landscape architectural topics. The strategy itself is actually quite limited in its form and effect in our detailed discussions of examples, but it provides the essential context and logic for the investigation and its choice of design, methods, and techniques. Our hierarchy of terms is as follows:

1. Strategy: An agenda of thought and action for knowledge formation (Nine strategies are classified in Table 1.1)

2. Research design: The structure of how to choose, structure, or limit the evidence vis-à-vis the query (e.g., sampling frame or generative design)

4. Methods: Procedures of investigation, some serving more than one strategic category (e.g., historiography or survey)

5. Analytical techniques: The tools of investigation, almost all serving multiple strategies and designs (e.g., depth interview, statistical analysis, or coding)

Table 1.1 Strategies of Inquiry

Questions of research strategy in landscape architecture are neither new nor trivial. There have been intense debates within the discipline in recent decades as to the legitimacy of different research paradigms. Each paradigm carries its own presuppositions, and typically each commentator advocates for his or her own position. Cross-disciplinary investigation is increasingly common, yet boundaries between fields of knowledge and the validity of “borrowing” different ways of creating knowledge are increasingly contentious, particularly in relation to the closely related discipline of architecture.

As well as points of tension, there are also significant gaps in knowledge and research activity. This raises further questions: How does the discourse of “how we know what we know” shape the discipline? Which, or whose, knowledge survives this scrutiny, becoming legitimated and eventually reproduced? What questions, evidence, and ideas are excluded? And what are the implications for practice?

1.3 The Gatekeeping Dilemma in Context

Our approach to these questions of scope and legitimacy is inclusive rather than exclusive. Overall we advocate a greater focus on the conceptual logic of inquiry, explanation, and evaluation of research approach and outcomes. There have been classifications of research methodology offered recently in related disciplines (Creswell 2009, Groat and Wang 2002, Laurel 2003), and within landscape architecture a conceptual framework has been proposed to reconcile the seemingly incompatible traditions of “objectivist” science and subjectivist arts (Swaffield 2006). However, the practical resolution of questions of legitimacy relies most heavily upon the judgment of “gatekeepers.” These judges of research quality include, among others, academic advisors and graduate examiners, administrators and appointment committees, acquiring editors and advisory boards, editors and peer reviewers, foundation managers and granting agencies, and jurors and critics.

Responses from Key “Gatekeeper” Informants

1. What criteria are used by your journal to evaluate the quality and validity of research and scholarship submitted for publication?

- Scholarship—quality and insight

- Method—coherence, integrity, and rigor

- Outcomes—significance, relevance, and originality

- Presentation—clarity and style

2. Does the choice and/or weighting of criteria change depending upon the topic of research, or is it standard across all submissions?

- In principle, largely standard

- In practice, nuanced according to the type of paper

3. Do you have an expectation or preference for certain acceptable research strategies in landscape architecture? If so, what are they?

- A broad range is acceptable (even desirable)

- Needs to be appropriate to the subject

4. Have you rejected any work in recent years because the research paradigm adopted is not acceptable to your journal? If so, what type of research was involved?

- Never specifically

- Typically, rejection occurs if the quality of work is “not good enough,” or subject is not sufficiently relevant to the target journal

5. How does the research paradigm of submitted work influence selection of referees?

- Suggests what type of expertise is relevant

- Ma...