![]()

1

Historical Perspectives of Male Health

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Identify the main components of male health in the United States and internationally

- Understand male health in historical, cultural, and global contexts

- Interpret epidemiological and statistical evidence as it relates to male health

- Explain how culture can enhance or reduce health in males in the case of health-related disparities

- Analyze risk factors for being born male

©iStockphoto.com/Mariya Bibikova

MEN AND BOYS account for 50% of the world population, which translates into approximately 3.35 billion people! (International Data Base [IDB], U.S. Census Bureau, 2008). Yet, live infant male birth rates continue to trail those of females: in the United States, for every 1,000 live births among mothers ages 15–44 years old, 7.5 males die, compared to 6.2 females (National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS], 2005).

How and why do these numbers relate to health? First, let’s take a look at the demographics of these baby boys. As of 2005, 4,138,349 babies were born to the following ethnic groups in the United States: 55.9% white/Caucasian, 23% Hispanic/Latino, 14.1% black, 5.3% Asian, and 1.0% Native Americans and Alaskan Natives. With mortality data showing that the majority of infant premature deaths occur in non-white populations, it is easy to conclude that there are health-related disparities among these populations (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2002). Families with low socioeconomic status (SES) are more likely to have issues accessing appropriate health care. In non-white populations there are more single-parent homes without adult males than there are single-parent homes with adult males (Clarke, Cooksey, & Verropoulou, 1998).

From a world perspective, males outnumber females until ages 45–49, when the numbers start taking a sharp downturn. By age 80+ women outlive their male counterparts by nearly 50% (IDB, 2008). What occurs between the ages of 0 and 44 and then from 45 to 80+? Age-adjusted rates remain relatively stable from birth until midlife for a variety of factors, such as intentional and unintentional injuries, disease and illness, and homicide. During the years 0–44, lack of preventative health care in some populations, such as marginalized or minority men, and reluctance to seek health care can drastically limit the health status of men (U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research, 2008). A recent survey of more than 1,000 men found that American men tend to delay medical care and also overestimate their health. Further, 92% of those surveyed said they wait a few days to seek medical care or advice when they are sick, in pain, or injured. Last, 55% reported not having a yearly physical examination and 42% said they had at least one chronic illness, yet nearly 80% described their health as being “good” or better (American Academy of Family Physicians, 2008). What do these data suggest? Are males delusional about their overall health status? Do males not want to acknowledge weakness or illness for fear of being viewed as unmasculine?

Many of these male notions and misconceptions about health begin in the early, formative years. Disease patterns that occur in youth and early adulthood that affect men as they age include cardiovascular disease, neoplasms (cancers), and unintentional accidents. According to 2004 data from the CDC, 321,973 men died of cardiovascular disease, including heart attack and stroke, 286,830 from cancers, and 72,050 from unintentional accidents (Heron, 2007).

Many of the aforementioned conditions and illnesses are preventable with aggressive primary prevention. A valid and reliable resource, such as this textbook, will help fill the need for a primary prevention tool. Throughout this book’s thirteen chapters, readers will study not just the diseases, illnesses, and problems that afflict males throughout the life span, but more important, where they come from and how they can be addressed and prevented. Should a baby boy be circumcised? Does a toddler show signs and symptoms of autism or Asperger’s syndrome? Does a boy show early signs of attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity? Why are more school-age boys than girls diagnosed with learning disabilities? Why do males have lower graduation rates from college than females? How does job stress add or detract from young adult health? What challenges do middle-aged men face beyond the “midlife crisis”? Why does the prostate continue to grow, yet some men continue to lose their hair? All of these questions and more are addressed from a sociobiological perspective for each life stage throughout this book.

This chapter provides an overview of what is meant by “male health,” looking at historical contexts that have forged the way we view males and their health in contemporary society, Western and non-Western ideals of being male, and what it means to be born a male in society.

WHAT IS MALE HEALTH?

“Real men wear gowns.” This was an advertisement in a popular health/sports medicine magazine. The scene depicts a man standing next to a woman at a social function at which the other people are dressed up enjoying a bit of socializing. What makes the advertisement unique is that the man is wearing only a hospital gown! What is the relevance of this advertisement to this book? Let’s break this advertisement down to its roots or elements.

First, the simple statement and accompanying image of a man wearing a gown has several connotations. What are they? Why do all of these possibilities surface? Many people would argue that the images and stereotypes conjured from this simple advertisement are a result of sociocultural bias. Others may argue that this image and terminology challenge what many cultures consider to be the masculine norm. In actuality, the advertisement is a public service announcement (PSA) aimed at promoting regular physical health checkups with primary care providers as men approach middle age.

What is a man? Defined, man is a term that describes a physically mature male; however, male refers to the biological traits of a person. Several aspects of being male and a man come into play, such as masculinity. The masculine norm can be elusive and has existed in a state of flux for centuries. Masculine standards have included being the provider, strong, silent, and practical, as well as the opposite of the female norm. While there certainly are many opposites between men and women, each has its own attributes that demand its attention.

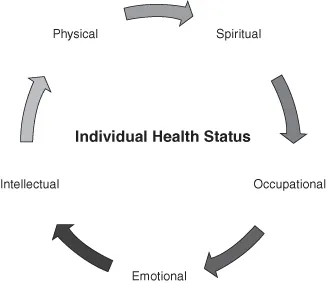

The concept of male health is best described as the elements and components that converge and foster either a positive health outcome or a negative health outcome. Several elements factor into a male’s overall health, including physical, emotional, occupational, spiritual, and financial. Health may be thought of as a confluence of these variables, similar to that of a Rubik’s Cube™ puzzle (Eberst, 1984). A primary challenge of the puzzle is to align the scrambled sections according to various colors. Not unlike life’s challenges, aligning one’s elements of health, is a primary aim of advancing one’s health. Balancing each section of one’s health (the puzzle) is achieved through learning and experiencing life. Adapting to change often promotes a healthier life perspective.

The Healthy and Healthier Man

Traditionally, health was viewed as merely the absence of disease, and conversely, disease was looked at as the absence of health. By today’s standards, these definitions could not be further from what constitutes health (Jadad & O’Grady, 2008). The term health and its close and inseparable counterpart, wellness, are comprised of many facets or prongs (Hawks, Smith, Thomas, Christley, Meinzer, & Pyne, 2008). Optimal health and wellness can be thought of as a balancing act among several key areas and concepts of wellness (see Figure 1.1).

- Physical health focuses on promoting a strong and vital body through good practices of nutrition, rest, exercise, avoiding harmful habits, and seeking medical care when needed.

- Mental and emotional health focuses on understanding one’s emotions and feelings and making stable, healthy, and positive lifestyle choices. An emotionally healthy person is able to accept his or her limitations and draws from life experiences and inherent personal attributes.

- Occupational health refers to workers’ abilities to provide for themselves and their families in health-promoting employment settings. Healthy work settings include both emotional as well as environmental attributes that help employees achieve optimal health, such as work resiliency programs, employee assistance programs, and exercise programs.

- Environmental health focuses on the relationship between a person’s physical environmental and its impact on his or her personal health. For example, protecting oneself from environmental hazards such as pollutants or poor air quality helps to promote better overall health.

- Spiritual health refers to a sense of connectedness with a greater power and gives life meaning and purpose. Spiritual health is enhanced by one’s morals, values, and ethics.

- Social health involves the ability to communicate and relate well to others in society. Positive social health allows for a better sense of community and social growth of the individual.

- Intellectual health focuses on thinking, thought processing, learning, and interacting with one’s world and environment in a creative manner.

The dynamic interplay among these concepts of health is what leaves a person with positive or negative health. It is rare that all aspects of health will be in alignment like a Rubik’s Cube (Eberst, 1984); however, health is optimized when a majority of the components of health and wellness align with each side of the puzzle.

So what comprises the “healthy man”? Ultimately, if we stick to the dimensions of health and wellness discussed, the healthy man is one who values and maintains a physically healthy body, attends to challenges to his mental and emotional health, approaches his job in a healthy and positive manner, demonstrates environmentally responsible behaviors, views himself as a part of something greater than himself for spirituality, enjoys fulfilling social relationships and interactions, and engages in intellectual pursuits. Many of us would strive to attend to these facets of health. However, how many men attain this level of optimal health? Evidence-based research appears to tell a different story. Whether in life expectancy, years of quality life, disease, health disparities, violence and aggression, or drug use, males are failing to live up to the ideal of the healthy man. Perhaps individually and in a public health sense, we should be focusing on developing a “healthier” man versus an ideal.

MALE HEALTH IN HISTORY

The Account of Adam

Many of us would not think to look to the Old Testament in the Bible or similar religious texts for examples of male health. Genesis states that Adam (the first male) was created in the image of God (Gen. 2:10, 6:9; New International Version [NIV]). With this comes the assertion of power and reverence in that Adam represents an image of the most revered concept in religion (in this case Christianity), God himself. Power and ultimately all matters resulting from this, including health, can arguably be placed on the shoulders of Adam and all of his descendants. We also see examples of traditional male roles through Adam and Eve when Adam “leads” and Eve “follows.” With leadership comes additional stress, both good and bad. Created in the image of God, as the first human being on Earth, and serving in the role of “leader,” Adam must have been placed in a remarkable position of expectation and stress. Further, Eve bore Adam two sons, Cain and Abel. One might argue that Cain bore the original sin of aggression and ultimately fratricide. In today’s society males are more likely to be homicide victims (nearly four times higher), commit violent crimes and general acts of aggression, and be perpetrators of domestic and intimate partner violence than their female counterparts (Heru, Stuart, Rainey, Eyre, & Recupero, 2006). The biblical account of course is only one account of the origin of man; many other written and oral traditions adhere to similar accounts of gender roles.

The role of the male in Western society remained virtually unchanged until recent times. Other cultures have embraced the male in different ways, with some theories and examples showing complete role reversals. To advance a healthy agenda for the modern male, we need to revisit our historical past and go beyond the scope of the Western, Judeo-Christian perspective.

Males in the Seventeenth Through the Twenty-First Centuries

For a majority of recorded history, patriarchal views were the predominant cultural tradition. To some extent, patriarchy still exists, albeit in other forms than what was once commonplace (Sanderson, 2001). For example, from the 1600s through much of the 1900s, a man was expected to be the provider (“breadwinner”) of the family...