![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction to Sustainability

INTRODUCTION

Sustainable landscape management is a philosophical approach to creating and maintaining landscapes that are ecologically more stable and require fewer inputs than conventional landscapes. They are still artificial landscapes inserted into highly disturbed site environments and maintained to meet the expectations of owners and occupants. Sustainability is a relative concept and more a goal to strive for rather than a well-defined end point. There will never be truly self-sustaining constructed landscapes, only landscapes that are more or less sustainable than our current efforts. To better understand sustainability, it is useful to review the historical origins of the movement. This will shed light on why there is so much interest in the topic.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

The sustainability movement started shortly after the industrial revolution, beginning in the 18th century. As cities became more industrialized and the ability to extract and use resources increased, it was not long before cities grew to an unprecedented scale and the population began to explode. This transformation changed everything and quickly brought out detractors. It was 1798 when Thomas Malthus, an English country parson, penned his Essay on Population. In this writing, he questioned whether the earth could support geometric population growth (Malthus 1798). He feared the poor (the laboring classes) would reproduce faster than the world could provide for them, resulting in a total collapse of society. Malthus’s essay sparked reaction and has been debated almost continually since it was published. The heart of the debate is whether nations can keep finding and extracting enough resources to support a constantly increasing population without running out.

The philosophical discussion deals with political and economic theory. Many of the major figures in the sustainable development movement have been economists. While industrialists were busy exploiting resources, there was always a skeptical economist who would raise his or her hand and say, “Wait a minute. I think we may have a problem.” In 1865, William Jevons wrote The Coal Question (Jevons 1865). In Jevons’s time, coal was the only functional source of energy. He hypothesized that as population (and demand for coal) increased, Britain would exhaust its reserves and the economy would fail. He proposed that the British economy would slowly decline and be displaced by other countries with more natural resources. In terms of coal, he was essentially correct. It never occurred to him that other energy sources would ever be economically feasible (which was a big mistake). Two things can be learned from Jevons: first, hard-and-fast predictions will probably be wrong; and, second, technology will attempt to solve any problem caused by misuse of resources.

The idea that there is a technological fix for every problem is debated among those interested in sustainability. Even though humankind has been incredibly resourceful in finding new technological solutions for energy resources, there is a nascent feeling among proponents of sustainability that the world cannot indefinitely rely on innovation to find ways to exploit the earth’s resources. In their view, it is time to find ways to avoid depleting those resources and (perhaps) even enhance them.

Prior to today’s sustainability movement, countries supported ever-increasing populations by extracting resources to produce food and other staples without regard for the environmental consequences. What these efforts were doing to the earth or how they might affect its capacity to provide for future generations did not factor into the equation. For example, the basic strategy for obtaining oil has always been to find new places to drill and to drill deeper. Oil companies have scoured the earth using an incredible array of technologies in search of more oil. Drilling occurs in climates and locations that would have been impossible a hundred years ago. As such, each new source seems to increase the potential for environmental catastrophes (e.g., the Exxon Valdez in 1989 and Gulf of Mexico in 2010).

EMERGENCE OF THE SUSTAINABILITY MOVEMENT

There is no verifiable starting point for the current sustainability movement. It seems to have converged from several different broad ideas concerning our relationship with the natural world. Some of the key figures who have contributed to the discussion include Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, John Muir, Theodore Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot, Aldo Leopold, Rachel Carson, and Ian McHarg. Their history provides a better understanding of how the sustainability movement has evolved to the present. This discussion will consider the landscape management perspective.

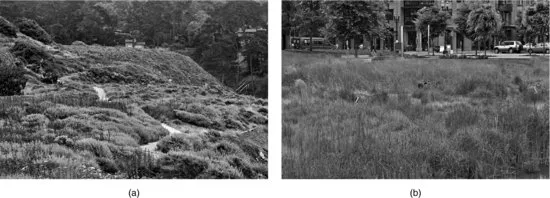

Olmsted and Vaux

In the mid-1800s, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux partnered to develop the Greensward Plan for an urban park, now known as Central Park, in New York City. Even though the park was built on largely derelict land and required massive efforts to reconfigure the topography, these two artists produced a relatively wild and natural landscape that provided a welcome natural experience for the public. This came at a time when New York City was becoming increasingly industrialized and home to a huge labor force living in squalid tenement buildings. Population density was high, and workers were unable to escape the summer cholera epidemics. There were virtually no recreational options available to the working class. Life was hard for all but the wealthy.

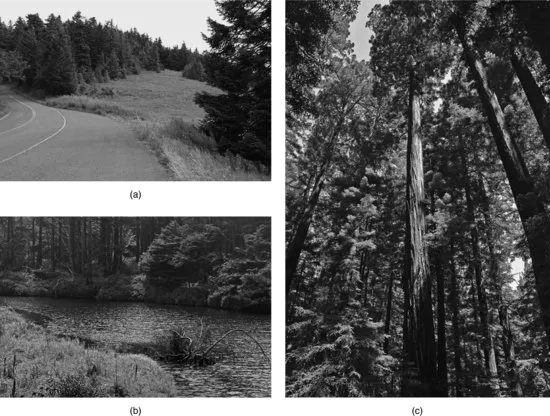

Olmsted, the more dominant and vocal of the two, stood out as a passionate advocate for natural spaces in the city that would provide passive recreational activities for city dwellers. He viewed landscapes in the same manner as a naturalist would view a forest or prairie (Figure 1-1). Olmsted and Vaux’s designs created apparent natural landscapes that were, in fact, manufactured. Interestingly, though Olmsted obsessed over plant materials, he felt constrained by his lack of knowledge of plants and their appropriate niches in the landscape.

Olmsted’s and Vaux’s careers (and those of Olmsted’s sons) spanned a period of major public park development throughout the United States. Their efforts enhanced the public’s awareness of the value of beautiful and natural-looking landscapes. During his 50-year career, Olmsted was involved in designing some of the most outstanding and enduring public parks in the world. He was well ahead of his competition and today is widely regarded as the father of landscape architecture in the United States.

Preservation versus Conservation

Coming from a completely different perspective and emerging as a major voice during the last half of Olmsted’s career was John Muir. Muir was a self-taught naturalist who devoted much of his life to extolling the virtues of the natural world and who lamented the defiling of the wilderness by humans. Muir felt wilderness should be preserved for its own sake (Figure 1-2).

A visit to Yosemite in California in 1868 fueled Muir’s love of wilderness and nature. He spent much of his time exploring this region and quickly began to understand the negative impact of cattle and sheep grazing on fragile ecosystems. During this time, the nation was rapidly expanding, and opportunists were quick to exploit all natural areas as they sought their fortunes. This new breed of entrepreneurs disregarded the intrinsic value of natural areas and how resource extraction threatened to destroy nature.

Muir’s efforts eventually led to the preservation of several wilderness areas, notably Yosemite Valley in California. Muir founded the Sierra Club in 1892, long considered one of the most powerful voices for preservation of wilderness. A split developed between preservationists like Muir, who believed wilderness should be left alone and appreciated for its beauty and spiritual values, and conservationists such as Gifford Pinchot and President Theodore Roosevelt, who believed that forests and wilderness areas should be preserved but also be profitably used for grazing, timber harvest, and other commercial activities (Figure 1-3). This difference in opinion continues today and is reignited whenever plans are announced for logging in old-growth forests or when areas containing endangered species are targeted for development.

Emergence of the Land Ethic

In the 1940s, Aldo Leopold expressed a more philosophical view of the relationship between nature and humans. Trained as a forester, Leopold spent much of his career working with wildlife in the arid Southwest and later in the Midwest of the United States. Although he held strong opinions about how the earth should be treated, he was not entirely opposed to using natural resources for hunting and fishing or even mining. His opinion was different from the opinions of other environmentalists and his message less extreme than that of the preservationists.

In 1949, shortly after his death, Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac was published. This collection of essays starts with the naturalist’s year in Sand County, Wisconsin, followed by his experiences in the western states, where he observed human successes and failures in understanding ecosystems in a diverse array of climates. The text concludes with an elaboration of his philosophy about wilderness, conservation, and, ultimately, what he called “the land ethic.” The land ethic is best explained in his own words:

All ethics so far evolved rest upon a single premise: that the individual is a member of a community of interdependent parts. His instincts prompt him to compete for his place in that community, but his ethics prompt him also to co-operate (perhaps in order that there may be a place to compete for). (Leopold 1949)

The land ethic simply enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively: the land. (Leopold 1949)

He goes into more detail in later passages:

A land ethic of course cannot prevent the alteration, management, and use of these “resources,” but it does affirm their right to continued existence in a natural state. (Leopold 1949)

In short, a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow-members, and also respect for the community as such. (Leopold 1949)

Leopold believed that people need to view the natural world in terms of a biotic pyramid (what today is known as an ecosystem), defined by interconnected webs of relationships among soil, plants, and animals. How humans impact the land affects, often profoundly, the relationships among all participants, and they need to be mindful of everything they do managing the “land.” Even though Leopold’s emphasis was on wild lands, his message is just as powerful when considering constructed landscapes (Figure 1-4).

Post–World War II

Reflecting on the times, it is interesting to consider that when Leopold was working, there were only about 125 million people in the United States. The nation had just emerged from the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl and had yet to develop the fertilizer and chemical industries of modern times. The dawn of the chemical age began just after World War II and had profound impacts on every facet of our relationship with the earth and all of its inhabitan...