eBook - ePub

Psychology in Social Context

Issues and Debates

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Psychology in Social Context: Issues and Debates provides a critical perspective on debates and controversies that have divided opinion within psychology both past and present.

- Explores the history of psychology through examples of classic and contemporary debates that have split the discipline and sparked change, including race and IQ, psychology and gender, ethical issues in psychology, parapsychology and the nature-nurture debate

- Represents a unique approach to studying the nature of psychology by combining historical controversies with contemporary debates within the discipline

- Sets out a clear view of psychology as a reflexive human science, embedded in and shaped by particular socio-historical contexts

- Written in an accessible style using a range of pedagogical features - such as set learning outcomes, self-test questions, and further reading suggestions at the end of each chapter

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Psychology in Social Context by Philip John Tyson, Dai Jones, Jonathan Elcock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Nature of Psychology

Contents

Learning Outcomes

Introduction

1.1 What Is Psychology?

Focus Box 1.1 Psychology and psychology

1.1.1 Popular views of psychology

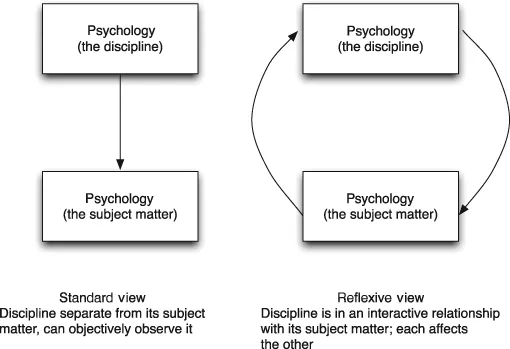

Figure 1.1 The relationship between the discipline of psychology and its subject matter

1.1.2 Defining psychology

1.1.3 The emergence of psychology

1.1.4 Contemporary approaches to psychology

1.2 Psychology as Science

1.2.1 The appeal of science

1.2.2 The nature of science

1.3 Issues in scientific psychology

1.3.1 Issues in the quality of scientific psychology

1.3.2 Issues with bias in scientific psychology

1.4 Chapter Summary

Self-test Questions

Thinking Points

Further Reading

Learning Outcomes

When you’ve finished reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand views of psychology as the systematic study of mind and behaviour.

- Identify the range of approaches adopted in finding explanations in psychology.

- Recognize the ways in which psychology can be approached scientifically.

- Evaluate arguments about the appropriateness of scientific psychology.

Introduction

This book introduces a range of issues and debates in psychology by looking at how psychology is actually done. We’ll look at several examples of how psychology has engaged with controversial social issues, and use these examples to highlight debates about the way in which psychology is conducted, presented, and understood. Along the way, we’ll see that the discipline of psychology is a socially embedded activity that uses a number of methods to produce knowledge about human nature and human behaviour. This activity is conducted by psychologists with multiple purposes behind what they do. This range of methods and purposes leads to psychology being a very diverse discipline, investigating every aspect of human life from a variety of perspectives (Richards, 2010). The result is that different kinds of psychology produce different kinds of knowledge about mental life and behaviour.

Although there is great diversity in the discipline, there is a standard view of psychology that is most commonly presented in popular writing, most often taught in institutions, and most frequently practised by researchers and practitioners. This view sees psychology as an objective science that uncovers the truth about human behaviour (Fox & Prilleltensky, 1997). Most kinds of psychology conform to this view to varying degrees, but there are some psychologists who have fundamental disagreements with it. Such psychologists describe themselves as critical psychologists, and emphasise the ways in which the discipline has particular relationships with its members, its host society, and its subject matter (Jones & Elcock, 2001).

In this book, we’ll consider some of the claims of critical psychologists by looking at examples of what psychology has done, and what it has claimed, from the past and present. In looking at these examples, we’ll consider why psychology has produced the knowledge that it has, and evaluate the extent to which the standard view of psychology is accurate, or the claims of critical psychologists are valid. Before we can do this, we need to describe the standard view of psychology more fully. We do that in this chapter. We start by considering what the discipline of psychology claims to be, and where it comes from, before looking at the range of theoretical approaches that psychologists adopt in trying to explain human behaviour. We’ll then look particularly at how scientific method can be applied to psychology, before considering some debates about whether such a scientific approach is appropriate.

1.1 What Is Psychology?

The term psychology is much used, but also much mis-used. Throughout this book, we will use the term to refer to the academic and professional discipline that investigates mental events and behaviour, and dysfunctions of these. There is a problem here, though, because those things the discipline investigates – mental health, behaviour, and so on – are also called psychology. So, psychology is the discipline that has as its subject matter psychology! Focus Box 1.1 discusses the relationship between the discipline and its subject matter in more depth.

Focus Box 1.1 Psychology and psychology

The term psychology can refer to a particular subject matter – mental states, behaviour, disorders, and the like – and to the academic and professional discipline that investigates that subject matter. This distinction between the discipline and its subject matter is important. The standard view of the discipline is that it is separate from its subject matter, and is able to objectively observe and theorise about it. So, just as a physicist can investigate gravity objectively, without affecting it, so can the psychologist investigate attitudes without affecting them. This view supports the use of the scientific method to investigate topics in psychology, just as it is used in natural sciences like physics.

An alternative view is that there isn’t a clear separation between the discipline of psychology and its subject matter. Rather, psychologists are influenced by their own psychological states in doing their work; and the work of psychologists influences people’s psychology, the subject matter of the discipline. We can say that there is a “reflexive” relationship between the discipline and its subject matter (Jones & Elcock, 2001), such that they affect each other interactively (see Figure 1.1). As an example, we’ll see in chapter 4 that psychologists have long investigated the question of whether different ethnic groups differ in ability, particularly regarding intelligence. Typically, those psychologists who believe beforehand in the existence of such differences find evidence to support those beliefs, whereas those psychologists who don’t believe in such differences find evidence to support their views. The contrast between the two sets of claims is largely due to differences between the views of the psychologists concerned. In addition, the effect of the work is to persuade people of the existence or not of such differences, which then changes their behaviour, which in turn changes the experiences of different ethnic groups and hence the results of future studies in the same area. As Valentine (1992, p.4) states, “[A]ctually doing psychology constitutes part of its subject matter.”

The idea that there is a reflexive relationship between the discipline and its subject matter is at the heart of this book. When we look at controversial social issues, such as race and IQ, we’ll see that the views of psychologists can influence the results they report, lending support to the idea that the discipline does not stand apart from its subject matter in the way that the natural sciences do. If this is the case, then we need to think differently about many of the claims that psychology makes.

The term psychology is also used more widely. When we think about the performance of sportspeople, we may attribute success or failure to “their psychology”. When we think about our own or others’ behaviour, we may say that we’re psychologising. We’re surrounded by claims about psychology in the media, and there’s a large market for “popular” psychology. All these uses of the term are reasonable, but by and large they are beyond the scope of this book. Our focus will be on the discipline, and so we’ll start by setting out what we think the discipline of psychology consists of.

1.1.1 Popular views of psychology

Given how frequently the term psychology is used, it should come as no surprise to learn that there are a range of different views of what psychology is. Unfortunately, popular views of psychology are usually at odds with the reality of the discipline. Before giving our definition of psychology, we’ll look at some of these popular views. Popular, or “everyday,” views of psychology fall into two broad groups. On the one hand, people sometimes think of psychology in terms of self-help or self-improvement, and relate it to the general category of “mind, body, and spirit” so popular with booksellers. On the other hand, there are a set of views of psychology as an academic and professional discipline. We’ll look at both of these.

Figure 1.1 The relationship between the discipline of psychology and its subject matter.

This book takes the view that there is a reflexive relationship between the discipline of psychology and its subject matter. Each influences the other.

This book takes the view that there is a reflexive relationship between the discipline of psychology and its subject matter. Each influences the other.

For many people, the idea of psychology is synonymous with self-help. In part this is due to the way psychology is presented in the media (Howard & Bauer, 2001), and in part it is due to the extraordinary growth of the self-help industry (Justman, 2005). Psychology in the media often consists of untested claims and advice, myths, and pseudo-psychological concepts of limited validity (Furnham, 2001). This collection of topics is sometimes termed popular or pop psychology, and constitutes many people’s idea of psychology. There is concern within the discipline of psychology about the influence of pop psychology. Stanovich (2009) suggests that it gives the illusion of expert knowledge that allows any individual to take control of their life. This is a worthy goal, but many of these “experts” lack expertise, and pop psychology often obscures the findings of the psychology conducted by academics and professional practitioners. Such are the concerns about pop psychology that we examine it in more depth in Chapter 13. It suffices for now to say that pop psychology is an inaccurate representation of what the discipline is like (Jones & Elcock, 2001).

Despite the prevalence of popular psychology, people recognise a separate discipline of psychology that consists of academics and professionals doing research and conducting interventions. However, here too there is a misunderstanding of what psychology is like. For many, disciplinary psychology is synonymous with the work of Freud; for example, Furnham (2001) suggests that 90% of people in the street identify Freud as a psychologist, but only around 5% can identify a living psychologist. Freud’s psychodynamic approach was successful with the public, with people finding it easy to imagine that subconscious motivations and drives may influence our behaviour (Richards, 2010). However, we shall see that it had a limited influence on the discipline of psychology. The other (less) common view of disciplinary psychology is of a person in a white coat shaping people’s behaviour through a system of rewards and punishments. This reflects the behaviourist approach that was widespread from around the 1930s to the late 1950s, but this view has little relevance to contemporary academic psychology.

One reason why these popular views persist is that the discipline has done quite a poor job of presenting itself to the public. Despite a long tradition of psychologists urging each other to be accessible and relevant, much disciplinary psychology remains obscure and arcane to the layperson. Most publications in psychology are dry and academic, and require education in the field to be understandable. There have been some notable recent attempts to give more accessible introductions to the discipline, including Stanovich (2009) and Jarrett and Ginsburg (2008). However, we shall see that although psychologists have their own views of what their discipline is, these views may themselves be mistaken. In this book, we hope to give an alternative understanding of the nature of psychology.

1.1.2 Defining psychology

Psychology has been defined in many different ways, but the usual definition is as “the science of mind and behaviour” (e.g. Gross, 2005). This tells us both the subject matter of psychology and the methods that most psychologists prefer to use, those of science. Actually, this definition both reveals and obscures the diversity of modern psychology: reveals, because its subject matter is extensive, and any discipline attempting to investigate such a large subject must be diverse; and obscures, because it suggests that psychology is a single entity, with a unified purpose and approach. As we shall see, there is considerable debate within psychology about the methods that should be used, and the purposes of psychological investigation.

Given the diversity of modern psychology, a safer definition might be “the systematic study of mental life and behaviour”. This suggests that psychology investigates a range of phenomena using a range of techniques, with an emphasis on the use of empirical evidence to support theory (Stratton & Hayes, 1999). This emphasis on systematically gathered evidence is what unites psychology, and differentiates it from other approaches to explaining mind and behaviour. For most psychologists, this means using the scientific method, and such is the importance of the scientific method that we devote a large part of this chapter to discussing its use. Broadly speaking, scientific approaches to psychology aim to ascertain truths about human psychology through objective observation. However, some reject this view and claim that human psychology cannot be investigated objectively. There is debate in some parts of psychology about the nature of the discipline, and particularly about the validity of the scientific method (e.g. Bell, 2002; Gross, 2009). Over the course of this book, we use evidence of how psychology has been conducted to tell us more about these debates. For example, if a psychologist produces theories about racial differences in IQ that seem to be influenced by their political views, then we might doubt their objectivity (see chapter 4). We hope that by the end of the book, the reader will be better able to interpret psychological claims.

1.1.3 The emergence of psychology

The idea of investigating “mind and behaviour” isn’t a novel one. As a social species, it is difficult to see how people could not think about such things. We need to understand how the world around us works. We develop some understanding of how the physical world works; for example, we expect most objects to stay where we put them and not to fly away, unless the object in question is a bird. This physical understanding is sometimes called naïve physics. Similarly we have a naïve, or “everyday”, psychology that is the sum of our understanding of the social and psychological world (Furnham, Callahan, & Rawles, 2003). However, this everyday psychology is flawed in a number of different ways: it is subjective, idiosyncratic, and often inaccurate (Jones & Elcock, 2001). Because of this, from the earliest times scholars have attempted to find better ways of explaining mind and behaviour, developing disciplines such as philosophy and theology. We use the term reflexive discourse to refer to such approaches to explaining human nature. Reflexive discourse is an important part of any field that deals with people, including for example education, medicine, and literature. Educators, clinicians, and writers all deal with aspects of human nature, and characterise people in particular ways. In this sense, we can see the discipline of psychology as a distinct form of reflexive discourse, as is everyday psychology. Psychology emerges to provide better explanations of human thought and behaviour than other forms of reflexive discourse, by using systematically gathered evidence.

We can learn a lot from studying the development of different forms of reflexive discourse, and of psychology in particular. Ebbinghaus (1908, p.3) famously stated, “Psychology has a long past, but its real history is short.” This is presented in introductory textbooks as meaning that psychology can trace its roots to ancient Greek philosophy, and that psychology answers the same kinds of questions as philosophy but uses the “superior” scientific method to do so. As such, psychologists claim the kudos of the ancient Greeks, together with the kudos of the scie...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Halftitle page

- Title page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- About the Authors

- Preface

- Chapter 1: The Nature of Psychology

- Chapter 2: Psychology and Society

- Chapter 3: Psychology, Intelligence, and IQ

- Chapter 4: Psychology and Race

- Chapter 5: Psychology and Women

- Chapter 6: Beyond Nature Versus Nurture

- Chapter 7: Psychology in Service to the State

- Chapter 8: Ethical Standards in Psychology

- Chapter 9: Personality and Personality Tests

- Chapter 10: Psychology and Mental Health

- Chapter 11: Freud and Psychology

- Chapter 12: Parapsychology

- Chapter 13: Psychology in Everyday Life

- Chapter 14: Further Issues in Psychology

- Chapter 15: Psychology at Issue?

- Selected Glossary

- References

- Index