![]()

Chapter 1

What is the Congressional Effect?

Congressional talk is not cheap. In the summer of 2011, the awful spectacle of Congress's inability to timely resolve the budgetary issues regarding our debt cap and the resulting downgrade of United States debt took a heavy toll on the stock market. What is so disturbing is that in their brinksmanship, our lawmakers never seem to consider just how much their actions cost us. What is truly upsetting is the amount of wealth destroyed merely by political talk, even when that talk doesn't lead to action. This wealth destruction is the Congressional Effect. It is empirically demonstrated in the aggregate by looking at how the stock market is affected on a daily basis by Congress. In turn, this broad Congressional Effect is generally comprised of a series of legislative impacts on sectors and, sometimes, individual companies.

From 1965 through 2011, measuring each of the 11,832 trading days during that period, the price of the Standard & Poor's (S&P) 500 Index rose at an annualized rate of less than 1 percent on days Congress was in session, but over 16 percent on days they were out of session. This enormous difference between in-session days and out-of-session days is not coincidental, but rather reflects the cumulative effect of unintended adverse consequences on the U.S. stock market from anticipated and actual congressional legislative initiatives. Whenever Congress focuses on an industry with the potential for changing the rules for that industry, investors have to discount what Congress may or may not do to change the business plan of the companies in that industry. Some investors wait for the final version of the new rules so they have more certainty about the business models of the companies before they buy. But sellers often have to sell for reasons having nothing to do with the latest news about an industry. When there are disproportionately more sellers than buyers, you have periods of underperformance, which happens much more frequently when Congress is in session.

All of this is aggravated by the sheer number of opportunities for Congress to make news. Since there are 535 members of the House of Representatives and the Senate, with 23 House committees and 104 House subcommittees, and 17 Senate committees with 70 subcommittees, there are many industries that Congress can affect on any given day.

This book looks at the Congressional Effect in depth, and offers several strategies for how to optimize your portfolio. Once you understand the nature of the incentives that each politician has that collectively result in Congress's relentlessly working against your portfolio, you can better use their efforts to your advantage. The rest of this chapter describes how the theory of Congressional Effect was discovered and the evidence supporting it.

How Was the Congressional Effect Discovered?

For me, late Friday afternoon is the business equivalent of being in the shower: The pressure of the week is spent and it's OK to let your mind wander. I get lots of my ideas then. At these times, I am almost always tired from working my butt off, and the only people you can reach are your old friends and acquaintances, who don't mind having a little downtime to see the latest stuff you are mixed up in.

I remember the particular Friday afternoon in January 1992 that I discovered the Congressional Effect. The weather was freezing in New York City, in the 20s and windy. The sky was that clear, cold blue you get when the sun is bright and the day is short. I was head of investment banking at a scrappy, growing Wall Street research firm, but in those days we were quite small and could only afford offices in Manhattan's Garment District. (For those of you who know Manhattan, this is a little incongruous. It was almost the investment-banking equivalent of the set of Zero Mostel's version of The Producers.) My tiny office was about 50 square feet, the size of a cubicle, but in fact was a built-out room with 12-foot ceilings. Gary Glaser, perhaps the best analyst ever of the auto companies, had an office next to mine. In those days, Gary smoked four packs of cigarettes a day. If you ran your finger along the walls of his office, you could pick up the tar and nicotine. Things were grimy.

We didn't have much of a brand name in those days. We had to fight for every deal we did and for every dollar we raised for our clients. And at that moment in time, I was almost completely stalled. I had been trying to raise money for an industry that competed with cable TV. Over a year and a half, I had called on 200 banks and venture capital firms to raise money for terrestrial multichannel TV—a precursor of satellite TV using specialized frequencies—only to be told it would never work, the public didn't want competition, the banks would never lend to it, and so on. In many cases, I was calling on funds that had a vested interest in the cable industry, either through direct investments or by virtue of having investors connected to that industry. It was a brick wall. We needed to get to the wide public market and ask a broader array of buyers if they thought there was a need for competition for cable TV.

I had one client, ACS Enterprises, which had filed for a $10 million initial public offering (IPO). ACS provided cable TV programming to 30,000 paying customer households in Philadelphia and was trying to raise $10 million in a public offering. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) was dead set against ACS at that time and just bombarded the company with a parade of never-ending comments that felt like they were designed to make the company throw in the towel on raising more money. For example, after the prospectus had been on file with the SEC for three months, they asked the company to specifically state as an emphasized warning that it “might face unforeseen obstacles” in competing with the cable TV companies. We dutifully amended the draft prospectus and resubmitted it to the SEC. After three more months—an eternity to a small company starved for cash—the SEC came back and asked us to “spell out and specify” the unforeseen obstacles we might anticipate. We replied that they had made us put this warning in to begin with, and that if we knew what they were, they would no longer be unforeseen. All these pettifogging, time-killing requests from the SEC occurred against a background of a company running out of money and staring at bankruptcy.

I reacted quite stubbornly to the idea that the industry was not financeable and was racking my brain for ways to make my deals work in spite of the government and in spite of cable competition. I was stewing. It being Friday afternoon, I called a friend to complain about the horrid state of the world.

In the middle of my complaining about my deals, one of my friends, no doubt trying to cheer me up, told me they were probably stalled because the market in general feared the Buffalo Bills might win the 1992 Super Bowl. After all, this was their third consecutive trip to the big show, and it seemed this time they would finally get it done. There was then, and there still is, stock market folklore that when a team from the old American Football Conference wins the Super Bowl, the stock market will go down for the year. I told my friend not to worry, for sure Buffalo would lose, and even if they didn't, the January Effect would bail us out in the stock market. And if the January Effect didn't kick in, there would be a Summer Rally… and if not, the year would be saved by the Santa Claus Rally, and so on.

As it turned out, there was no need to worry, because the Dallas Cowboys crushed the Buffalo Bills 52–17, and the S&P 500 Index did indeed go up 10 percent that year. But the question did get me thinking about correlations. At that time, I was an investment banker raising money for small public companies, most of which competed with larger cable TV companies. I knew there was stock market folklore about seasonality and wondered if I could figure out a new way to play the stock market. There are hundreds of aphorisms about the stock market that pass for market wisdom in the same way campaign slogans are used by some voters to decide their election choices. The most famous is probably “Sell in May and go away.” It's based on the idea that not much news happens in the summer, so there is nothing to drive stocks higher. A different version of this is “Buy bonds in May and go away,” based, I suppose, on the good old days of yesteryear when bonds paid noticeable rates of interest and people led stable, dignified lives based on interest income. The underlying theory was that if there was going to be little market-moving news, it was better to be earning interest and have more fixed income exposure.

There were also other tactical timing phrases that suggested timing the market based on things like tax considerations and flows of funds. For example, there has long been the sense that there is a January Effect—that one can buy stocks in December and sell them higher in January. This is based on the idea that losing stocks are thought to be disproportionately sold at year end to get their losses realized for tax purposes, and repurchased in the new year. This fact, coupled with some increase in fund flows into retirement accounts in the new year as the result of year-end bonuses being paid, has made the logical case for the January Effect. Objectively, the data support that there has been a January Effect but to the extent it had a bigger benefit when capital gains taxes were higher and more of the market was in taxable funds, it has apparently subsided a lot since 1990. Then, too, there were the feel-good moments often associated with a rally—there is stock market folklore about a Santa Claus Rally and a Thanksgiving Rally and an Easter Rally, all supposedly coinciding with these holidays.

But at the time, while there were, and are, very sophisticated seasonality analyses that large firms use to inform their trading of every class of securities, there was to my knowledge no “Unified Theory” of market timing except that it was in general a bad idea. I had heard that Einstein was searching for a “Unified Field Theory” to explain the four physical forces of gravity, electromagnetism, and strong and weak nuclear forces with one common explanation. I asked myself if there might be one “Unified Field Theory of Tactical Market Timing”—a single overriding explanation for how stocks traded with respect to seasonality.

At this time in the early 1990s, my clients were all competitors of cable companies, but they had been adversely affected by new complicated rules the government had imposed recently on cable companies. The government had put a cap on the prices charged by cable TV companies, and as a result everyone in that business was struggling to stay afloat, even with apparent local monopolies. While this sounded like it was a good deal for consumers, it was actually a terrible deal for everyone: cable TV companies, their would-be competitors, and ultimately, consumers. Having thought the rules wouldn't change, many cable TV companies had borrowed to the hilt. Once the rules changed, cable TV companies and their lenders often found themselves in the twilight zone. Because they had local monopolies, the banks often lent to them at high multiples of cash flow. Once their rates were capped, the cable TV companies often would find themselves current on the interest they had to pay on their loans, but in violation of some of the covenants of their bank loans. In the aftermath of the savings and loan (S&L) crisis, these loans became known as “performing nonperforming” loans. Think about that term for a moment and you will begin to understand what happens when government intervenes.

These “performing nonperforming” loans became problem loans for the banks, which in turn had to reduce lending to the cable TV industry to satisfy the bank regulators. Cable TV expansion was halted. Since the cable TV industry was sick, raising money to compete with cable was even harder. The banks thought that if cable's loans were in trouble, creating new competition would only make things worse, and they mostly refused to finance any cable competitors. Consumers were worse off because although in the short term their prices were fixed, new entrants were prevented from entering competition and then offering more choices. When the government fixed prices, it did so at a time when offering 24 channels or 36 channels sounded like an incredible array of offerings. Just 20 years later, we know how feeble that offering is in hindsight. Imagine having the exact same 36 channels today.

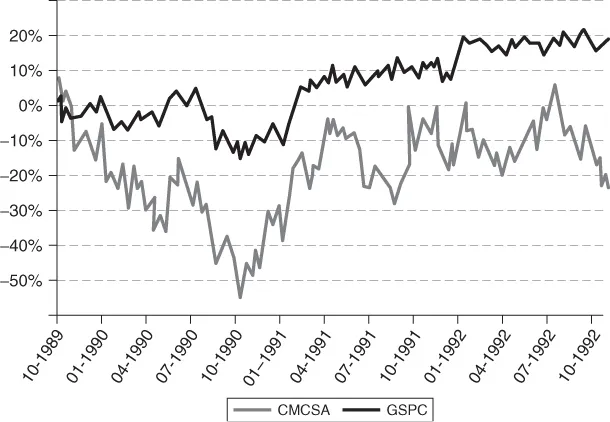

The threat of government action hurt all cable TV stocks during that period. Even Comcast, which we now know was perhaps the best cable TV company of its time, had its stock price stay virtually stalled from November 15, 1989, when the Cable Consumer Protection and Competition Act was first proposed, until it passed over the veto of President George H. W. Bush in October 1992. In that period in the aftermath of the law, its stock declined over 6 percent from $2.87 per share to $2.69 per share. In comparison, the S&P 500 Index rose almost 30 percent during the same period, so Comcast investors really suffered underperformance for becoming a government scapegoat. It is very bad for a stock to be demonstrably “dead money” while other stocks are participating in the greatest bull market in three generations. What made it worse was that during this time period Comcast grew its business from two million subscribers in 1988 to almost three million in 1994, mostly through organic growth, and increased revenues per subscriber, so it was growing its top line at over 15 percent per year and entering into the cellular phone business, but its stock went nowhere in those two and a half years1 (see Figure 1.1).

So there I was on that cold January afternoon. My clients were all competitors of cable companies, and the government was making it difficult for my first cable competitor client trying to get public money. All of the wireless cable TV companies had been swept up in the complicated rules the government had imposed recently on cable companies, and both cable and wireless cable companies were all struggling to stay afloat mostly because of government interference. The main reason was that the government had stepped in and told the cable TV companies they could not raise their prices. In turn, their stocks suffered and their would-be competitors suffered. Of course, with more competition, cable rates were likely to go down in real terms over time. And then it struck me: What if government action was the single explanation for the stock market folklore of the January Effect and the Summer Rally and the Christmas Rally and so on.… If government interference could lower the prices of cable TV companies and their shares prices, maybe it had the same impact on other industries, and maybe that was a factor, or even the factor, in the seasonality of stock prices. My firm was a well-respected institutional research firm (even if, or perhaps because, we were in the Garment District). Every morning, research analysts for specific industries would analyze the news and explain to our equity salesmen how it affected the companies they followed. Half the time, the news was about new thr...