![]()

Part I

Why Performance Is Not Enough

![]()

1

The Big Idea

Performance and Health

In early 2004, the Coca-Cola Company was struggling. Since the death of CEO Roberto Goizueta in 1997, its fortunes had suffered a sharp decline. Over that seven-year period, Coke's total return to shareholders stood at minus 26 percent, while its great rival PepsiCo delivered a handsome 46 percent return. Two CEOs had come and gone. Both had overseen failed transformation attempts that left employees weary and cynical. A talent exodus was under way as leaders in key positions sought to join winning teams elsewhere.

At this less than auspicious moment, enter Neville Isdell. As vice chairman of Coca-Cola Hellenic Bottling Company, then the world's second-largest bottler, he had enjoyed a long and successful career in the industry. Since retiring from that role he had been living in Barbados, doing consultancy work and heading his own investment company. However, the opportunity to lead the transformation of one of the world's iconic companies was a powerful lure, and he was soon installed in the executive suite at headquarters in Atlanta.

Isdell had a clear sense of what needed to be done. The company had to capture the full potential of the trademark Coca-Cola brand, grow other core brands in the noncarbonated soft drinks market, develop wellness platforms, and create adjacent businesses. But how could he follow these paths to growth when his predecessors had failed?

Experience told him that focusing solely on improving performance wouldn't get Coke where it needed to be. There was another equally important dimension that wasn't about the performance of the organization, but its health. Morale was down, capabilities were lacking, partnerships with bottlers were strained, the company's vision was unclear, and its once-strong performance culture was flagging.

Just a hundred days into his new role, Isdell announced that Coke would fall short of its meager third- and fourth-quarter target of 3 percent earnings growth. “The last time I checked, there was no silver bullet. That's not the way this business works,” Isdell told analysts.1 Later that year, Coke announced that third-quarter earnings had fallen by 24 percent, one of the worst quarterly drops in its history.

Having acknowledged the shortfall in performance, Isdell ploughed onward, launching what he called Coke's “Manifesto for Growth.” This outlined a path to growth showing not just where the company aimed to go, but what it would do to get there, and how people would work together along the way. Working teams were set up to tackle performance-related issues such as what the company's targets and objectives would be and what capabilities it would require to achieve them. Other teams tackled health-related issues: how to go back to “living our values,” how to work better as a global team, and how to improve planning, metrics, rewards, and people development to enable peak performance. The whole effort was designed through a collaborative process. As Isdell explained, “The magic of the manifesto is that it was written in detail by the top 150 managers and had input from the top 400. Therefore, it was their program for implementation.”2

It wasn't long before the benefit of addressing performance and health in an integrated way became apparent. Shareholder value jumped from a negative return to a 20 percent positive return in just two years. Volume growth in units sold increased from 19.8 billion in 2004 to 21.4 billion in 2006, roughly equivalent to sales of an extra 105 million bottles of Coke per day. By 2007, Coke had 13 billion-dollar brands, 30 percent more than Pepsi. Of the 16 market analysts following the company as of July 2007, 13 rated it as outperforming, and the other three as in line with expectations.

These impressive performance gains were matched by visible improvements on the health side. Staff turnover at U.S. operations fell by almost 25 percent. Employee engagement scores saw a jump that researchers at the external survey firm hailed as an “unprecedented improvement” compared with scores at similar organizations. Other measures showed equally compelling gains: employees’ views of leadership improved by 10 percentage points to 64 percent, and communication and awareness of goals increased from 65 percent to 76 percent.

But the biggest change could be felt in the company's halls. In a 2007 interview, Isdell noted that “When I first arrived, about 80 percent of the people would cast their eyes to the ground. Now, I would say it's about 10 percent. Employees are engaged.”3 When he returned to retirement in July 2008, he was able to hand over a healthy company that was performing well.

The Health of Organizations

Neville Isdell's actions at Coca-Cola revealed his intuitive grasp of a great paradox of management. When it comes to achieving and sustaining excellence in performance, what separates winners from losers is, paradoxically, the very focus on performance itself. Performance-focused leaders invest heavily in those things that enable targets to be met quarter by quarter, year by year. What they tend to neglect, however, are investments in company health—investments in the organization that need to be made today in order to survive and thrive tomorrow.

Perhaps surprisingly, we have found that leaders of successful and enduring companies make substantial investments not just in near-term performance-related initiatives, but in things that have no clear immediate benefit, nor any cast-iron guarantee that they will pay off at a later date. At IT and consultancy services company Infosys Technologies, for instance, chairman and chief mentor N. R. Narayana Murthy talks of the need to “make people confident about the future of the organization” and “create organizational DNA for long-term success.”4

So why is it that focusing on performance is not enough—and can even be counterproductive? To find out, let's first look at what we mean by performance and health.

Performance is what an enterprise delivers to its stakeholders in financial and operational terms, evaluated through such measures as net operating profit, return on capital employed, total returns to shareholders, net operating costs, and stock turn.

Health is the ability of an organization to align, execute, and renew itself faster than the competition so that it can sustain exceptional performance over time.

For companies to achieve sustainable excellence they must be healthy; this means they must actively manage both their performance and their health. Our 2010 survey of companies undergoing transformations revealed that organizations that focused on performance and health simultaneously were nearly twice as successful as those that focused on health alone, and nearly three times as successful as those that focused on performance alone.5

High performance is undoubtedly a requirement for success. No business can thrive without profits. No public sector organization can retain its mandate to operate if it doesn't deliver the services that people need. But health is critical, too. No enterprise that lacks robust health can thrive for 10, 20, or 50 years and beyond.

In fact, we would argue that strong financial performance can have a perverse effect: it sometimes breeds a degree of complacency that leads to health issues before long. In the months before the 2008 economic crash, the financials of most banks were at record highs. Similarly, oil at record prices of more than US$200 per barrel led the oil majors to declare record profits. As it turned out, this didn't mean that the banks and the oil companies were in the best of organizational health.

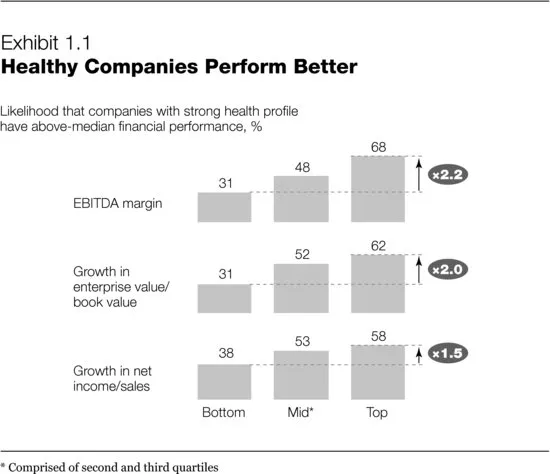

The importance of organizational health is firmly supported by the evidence. When we tested for correlations between performance and health on a broad range of business measures, we found a strong positive correlation in every case. For example, companies in the top quartile of organizational health are 2.2 times more likely than lower-quartile companies to have an above-median EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) margin, 2.0 times more likely to have above-median growth in enterprise value to book value, and 1.5 times more likely to have above-median growth in net income to sales (Exhibit 1.1). Across the board, correlation coefficients indicate that roughly 50 percent of performance variation between companies is accounted for by differences in organizational health.

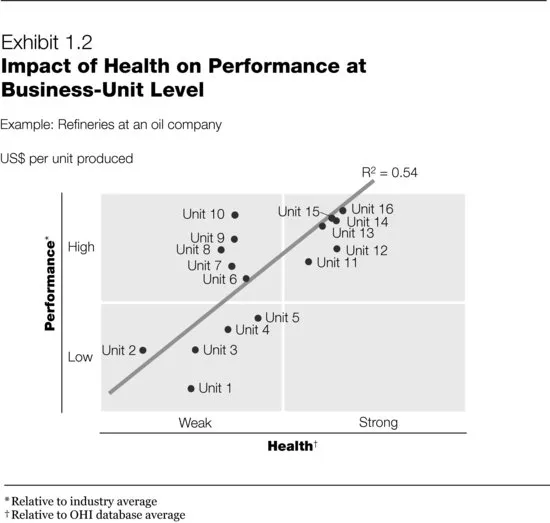

The results from our large sample of companies are mirrored by the results within individual organizations. At a large multinational oil company, we analyzed correlations between performance and organizational health across 16 refineries. We found that organizational health accounted for 54 percent of the variation in performance (Exhibit 1.2).

So strong is this relationship between performance and health that we're confident it can't have come about by chance. We'd be the first to admit that correlations need to be treated with caution. Take an example: education and income are highly correlated, but that doesn't mean that one causes the other. It's just as logical to argue that a higher income creates opportunities for higher education as it is to argue that higher education creates opportunities for a higher income (and even if it does, we can't infer that everyone who gains more education will have a higher income).

But our argument doesn't rely solely on correlations. On the strength of our research and analysis, we assert that the link between health and performance is more than a correlation, and is in fact causal. We argue that the numbers show that at least 50 percent of your organization's success in the long term is driven by its health, as we see in Chapter 2. And that's good news. Unlike many of the key factors that influence performance—changes in customer behavior, competitive moves, government actions—your organization's health is something that you can control. It's a bit like our personal lives. We may not be able to avoid being hit by a car speeding round a bend, but by eating properly and exercising regularly we are far more likely to live a longer, fuller life.

To shed more light on this causal link, here's an anecdote from our own experience. At McKinsey, we hold an internal competition called the Practice Olympics to develop new knowledge. A “practice” is a group of consultants dedicated to a specific industry (such as financial services) or function (such as strategy). In the Practice Olympics, teams of consultants compete to develop new management ideas and present them to a panel of judges at local, regional, and organization-wide heats. In 2006, the topic of performance and health made it through to the last round.

A few days before their final presentation, the performance and health team decided to add in an extra ingredient. Rather than drawing conclusions from a retrospective view of performance and health at various organizations, they asked themselves, “If we look at the health of today's high-performing companies, what does it tell us about their prognosis for performance in the future?” After reviewing publicly available information about Toyota, the team concluded that it would face performance challenges within the next five years. What were the reasons for this seemingly unlikely verdict? The team noted that Toyota's strong focus on execution meant that its organizational health was partly driven by how well it developed talent in key positions—something that was likely to come under strain before long because of the way it was pursuing performance.

In 2005, Toyota had set itself the aspiration to overtake General Motors as the world's largest carmaker. Renowned for its manufacturing expertise, the company had developed unusually close collaborations with suppliers during decades of shared experience. But this new aspiration would force it to expand so rapidly that it was hard to see how its supply-chain management capability could keep up. The company would have to become increasingly dependent on new relationships with suppliers outside Japan, yet it didn't have enough senior engineers in place to monitor how these suppliers were fitting into the Toyota system. And those engineers it did have wouldn't be able to give new suppliers a thorough grounding in how to do things the Toyota way in the limited time available.

In front of the judges at the finals of the 2006 Practice Olympics, the team put their stake into the ground. Toyota, with its proud reputation for building quality into its products at every step, was likely to have health issues that would affect its medium-term performance. Having sat through a day of novel ideas, the panel of judges reacted with outright disbelief. Toyota had just posted a 39 percent increase in net profit largely driven by U.S. sales, and appeared to be on a roll. One of the judges remarked that the team's prediction was “provocative, but completely ridiculous.”

Fast forward to 2010, and Toyota was in the throes of recalling a number of models on safety grounds. So serious was the situation that its president Akio Toyoda was called before the U.S. Congress to offer an explanation and an apology for the defects. The general consensus on the reasons for the breakdown in quality was in line with the turn of events that the team had foreseen four years earlier.

T...