eBook - ePub

The Roman Calendar from Numa to Constantine

Time, History, and the Fasti

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Roman Calendar from Numa to Constantine

Time, History, and the Fasti

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book provides a definitive account of the history of the Roman calendar, offering new reconstructions of its development that demand serious revisions to previous accounts.

- Examines the critical stages of the technical, political, and religious history of the Roman calendar

- Provides a comprehensive historical and social contextualization of ancient calendars and chronicles

- Highlights the unique characteristics which are still visible in the most dominant modern global calendar

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Roman Calendar from Numa to Constantine by Jörg Rüpke, David M. B. Richardson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

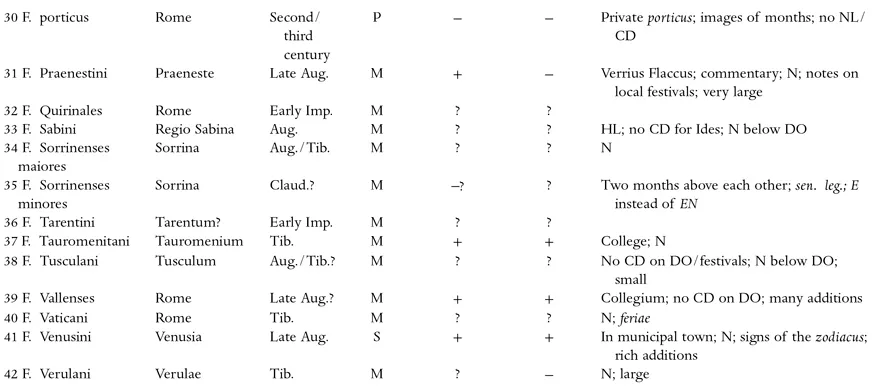

Map 1 and Table 1

Map 1 The map shows the distribution of preserved calendars (or calendar fragments) of the fasti type from the first century BCE to the fifth century CE

Table 1 List of known copies of fasti

B: Book. P: mural Painting. M: Marble. S: Stone (lime). N: Numerals indicating distance to next Kalends etc. CD: Character of the Day. DO: Days of Orientiations. HL: Hebdomadal Letters. NL: Nundinal Letters.

1

Time’s Social Dimension

Calendars have been invented in virtually every culture, for social life in a community requires structures defined by time as well as by space: in respect of each of these dimensions, chance circumstance and convention are commonly appropriated, and referred to ‘sacred places’ and ‘hallowed times’. The effect is to legitimize and simplify. In respect of calendars, it is rarely possible to distinguish between religious and technological history; this makes them susceptible, liable even, to revolutionary change. The history of the Roman calendar more than any other can be followed through many centuries and many such revolutions, during which it has absorbed or displaced other calendars, or, as in Gaul and Palestine, been instrumental in bringing them into being. The purpose of this book is to trace that history, from its discernible beginnings until, in the shape of the Julian Calendar, it was able to accommodate the requirements of a Christian conception of time. It is still in worldwide use today, in the little-changed form of the Gregorian Calendar.

But what is a calendar? The name given the Roman calendar was fasti, that is to say ‘list of court sittings’. The Latin word calendarium, on the other hand, meant ‘register of debts’; it referred to the kalendae/calendae, the first day of the month, when loans were given and interest payments fell due. Already in the Early Middle Ages, however, Isidore of Seville used the word calendarium in its modern sense of ‘calendar’. Thus neither of the Latin terms refers to the reckoning of time in the abstract. A ‘calendar’ is a document, a graphic, a text, with a particular look and a particular function. The reckoning of time is one aspect of such calendars, and calls for constant updating. Most extant examples of historical calendars contain amendments, additions, and deletions. Today too, most calendars are produced in forms that invite alteration and individualization. The resulting entries can change the face of a calendar, make of it a commentary or a historiographical work, complement it with specific texts and lists, or reduce it to a digest of locally relevant data. It is in the investigation of these different genres, and the inquiry into their communicative functions and the social circumstances of their creation, that the excitement of calendar histories resides.

Current sociological research provides a basis for understanding the problems facing a society in this context. Pride of place must belong to PITRIM A. SOROKIN and ROBERT K. MERTON, who, in 1937, on the basis of a few observations made by EMILE DURKHEIM,1 provided a first, brief but far-reaching analysis of the concept of time. Time is a social construct, to be understood not in an astronomical, quantitative sense, but socially and qualitatively.2 Systems for the reckoning of time, calendars among them, are founded on the need for coordination experienced by societies as they become more diverse;3 thus the first calendars are found in towns and cities.4 Religious festivals are only one of the elements recorded in such systems; astronomical phenomena are only occasionally called in aid, and then they are treated conventionally rather than strictly empirically.5 This ‘social time’ is characterized by an absence of homogeneity: its continuity is interrupted by significant intervals whose own identification as unified entities remains contingent, and different emphasis is typically given to periods of time of equal length.6

The work of NORBERT ELIAS leads to similar outcomes. He brought together some important reflections on the calendar in a long essay entitled An Essay on Time.7 His central idea is that of a gradually developing ‘self-control of people in conformity with time’, which becomes ‘the symbol of an inescapable and all-embracing constraint’.8 Time is a social institution with a coordinative and integrative function; only at a very late point in social development does the idea of ‘physical time’ emerge, and it is in this process of differentiation that the main interest lies.9 As, in ELIAS’ view, the symbols of time are subject to the pressure of ‘object adequacy’, the history of the calendar is linked in a particular way to the history of the measurement of time by observation of natural objects, and to the concept of time that emerges from that process: ‘On a small scale, the development of that calendar is a good example of the long-term continuity characteristic of the development of human knowledge and connected aspects of human societies.’10 In face of the radical dichotomy between social and physical time asserted by SOROKIN, ELIAS seeks to reconcile the two aspects. Of use in the analysis of actual calendars is his replacement of the romantic paradigm of an original unity of personal, socio-economic, and religious time, traces of which are supposedly preserved in the calendar, with the notion of a growing demand for systematization in societies of increasing complexity.

The momentum of this demand for coordination is highly relevant to the process ELIAS describes. ‘The more complex social systems now become, the more pronounced the prominence of abstract concepts and structures independent of external events in the cultural construct of time. Time is no longer perceived as a sequence of events, as alterations in natural phenomena, but construed as a linear succession of instants that no longer mediate meaning and expectations on the basis of connection with a physical occurrence; a continuing example in the Gregorian Calendar is, for example, Sunday, devoted to the glory of God. Time becomes event-neutral.’11 Only in this way can calendar-related constructs serve a society’s manifold requirements for synchronization and the management of expectations. The same set of requirements produces a demand for the calendar’s omnipresence, so that different versions, such as pocket calendars, wall calendars and tear-off calendars may emerge; as is evident from both modern and ancient examples, these different kinds of calendar by no means necessarily coincide in the coverage they offer.

The Roman calendar itself provides an instance of the problem of objectivity in the structuring of time. In analysing actual societies, we may be confronted with competing calendars, or situations where the relationships between mutually associated calendars are in some other way unclear. In some cases, the difficulty may lie in the fact that no written calendar exists. PIERRE BOURDIEU encountered problems such as these in his work among the Kabyles of the North-African Rif, when he attempted to produce a unified calendar from data provided by members of this ethnic group.12 BOURDIEU advises caution when interpreting the resulting synopsis: prior account must be taken of differing individual perspectives and local13 traditions.

Such instances can easily be augmented from everyday experience. Much calendar-related knowledge originates in quite disparate areas of life that, in the normal run of events, are not at all interrelated. Bluebell time, the strawberry season, Wimbledon, Indian summer, the autumn break, are all familiar concepts to us: but what dates14 would we give to an ethnologist who wanted to reconstruct our calendar? Should he provide for such periods to overlap, or do they succeed one another, and are there gaps? Our ethnologist would most probably seek to reconstruct a continuous year, so that the resulting calendar, in attempting to coordinate periods that are in fact discontinuous, would be a fiction that no individual would entirely acknowledge as ‘their’ calendar.

The resulting problems of recognition can easily be envisaged. It is hard to believe that the reconstructed calendar would resemble one of the genres familiar to us, and we would accordingly be unwilling to be bound by it. This binding character and the fact of publication are mutually dependent. The beginning of summer is astronomically determined, published, and thus unambiguously defined, whether or not it rains on 21 June. Even the beginning of the strawberry season does not depend solely on nature; it is determined in a discourse that includes classified advertisements, placards, and word of mouth. In the simplest as in the most complex societies, the natural benchmarks of time need social clarification and definition.15 On the other hand, not every binding date is widely publicized a long time in advance; publication may be restricted to the circle of those immediately affected, and may not occur until immediately prior to the event, or even at a later time.

These few excursions into our everyday relationship with ‘calendars’ go to show that a historical analysis of such phenomena is not the same thing as a history of astronomy in the cultures in question. It is not the calendar as such that merits our study, but its mediated forms, and the ways they function in society, and in its institutions and subordinate groups. The purpose of this book is to submit the calendars developed in the city of Rome from its earliest period to that kind of attention. After an initial analysis of extant examples of calendars (Ch. 2) it will therefore be necessary, in the absence of archaeological evidence or authentic ancient testimony, to reconstruct the earliest Roman calendar systems on the basis of Late Republican and Imperial-Period accounts and theories regarding that earlier history. Especially relevant here is the reconstruction of the lunisolar, so-called pre-Republican calendar (Ch. 3), which forms the essential background to an understanding of the significance of the mid-Republican calendar reform (Ch. 4). The key to the question of the ‘official version’ and its religious function (Ch. 5) lies in the publication of the fasti by Cn. Flavius at the end of the fourth century BCE. The sections that follow are designed to substantiate further the conclusions arrived at so far. They deal with the problem of pontifical intercalation (Ch. 6), the brief entries, the dedication days, and the historical notes (Ch. 7). How did these arrive in the calendar? But, above all: into which calendar did they arrive? Other questions to be answered here concern the actual graphic models for the explosion of calendar production in the Augustan age, and the conception of the fasti that provided the basis for the Augustan project (Ch. 8).

The remainder of the historical survey is devoted to the history of the Imperial-Period calendar (Ch. 9). It inquires into the breaks in the tradition: first, why did marble calendars remain confined to the Early Principate, in contrast to all other epigraphic genres, whose incidence continued to increase until the Severan Period, at the beginning of the third century? The final stage covered is the encounter in Rome between Christianity, with its Jewish calendar tradition, and the Julian calendar: here can be seen in sharp focus the capacity of calendar systems to embrace, accommodate, and resist change.

Notes

1 DURKHEIM 1915: 11 n. 1: ‘B...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Preface

- Map 1 and Table 1

- 1 Time’s Social Dimension

- 2 Observations on the Roman fasti

- 3 Towards an Early History of the Roman Calendar

- 4 The Introduction of the Republican Calendar

- 5 The Written Calendar

- 6 The Lex Acilia and the Problem of Pontifical Intercalation

- 7 Reinterpretation of the fasti in the Temple of the Muses

- 8 From Republic to Empire

- 9 The Disappearance of Marble Calendars

- 10 Calendar Monopoly and Competition between Calendars

- 11 The Calendar in the Public Realm

- Abbreviations

- References

- Index