eBook - ePub

The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Individual Differences

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Individual Differences

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Individual Differences provides a comprehensive, up-to-date overview of recent research, current perspectives, practical applications, and likely future developments in individual differences.

- Brings together the work of the top global researchers within the area of individual differences, including Philip L. Ackerman, Ian J. Deary, Ed Diener, Robert Hogan, Deniz S. Ones and Dean Keith Simonton

- Covers methodological, theoretical and paradigm changes in the area of individual differences

- Individual chapters cover core areas of individual differences including personality and intelligence, biological causes of individual differences, and creativity and emotional intelligence

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Individual Differences by Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, Sophie von Stumm, Adrian Furnham, Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, Sophie von Stumm, Adrian Furnham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicología & Personalidad en psicología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I: Individual Differences

An Up-to-Date Historical and Methodological Overview

An Up-to-Date Historical and Methodological Overview

1

Individual Differences and Differential Psychology

A Brief History and Prospect

A Brief History and Prospect

This handbook is devoted to the study of individual differences and differential psychology. To write a chapter giving an overview of the field is challenging, for the study of individual differences includes the study of affect, behavior, cognition, and motivation as they are affected by biological causes and environmental events. That is, it includes all of psychology. But it is also the study of individual differences that are not normally taught in psychology departments. Human factors, differences in physical abilities as diverse as taste, smell, or strength are also part of the study of differential psychology. Differential psychology requires a general knowledge of all of psychology; for people (as well as chimpanzees, dogs, rats, and fishes) differ in many ways. Thus differential psychologists do not say that they are cognitive psychologists, social psychologists, neuro-psychologists, behavior geneticists, psychometricians, or methodologists; for, although we do those various hyphenated parts of psychology, by saying that we study differential psychology we have said we do all of those things. And that is true for everyone reading this handbook. We study differential psychology: individual differences in how we think, individual differences in how we feel, individual differences in what we want and what we need, individual differences in what we do. We study how people differ, and we also study why people differ. We study individual differences.

There has been a long recognized division in psychology between differential psychologists and experimental psychologists (Cronbach, 1957; H. J. Eysenck, 1966), however, the past 30 years have seen progress in the integration of these two approaches (Cronbach, 1975; Eysenck, 1997; Revelle & Oehlberg, 2008). Indeed, one of the best known experimental psychologists of the 1960s and 1970s argued that “individual differences ought to be considered central in theory construction, not peripheral” (Underwood, 1975, p. 129). However, Underwood went on to argue (p. 134) that these individual differences are not the normal variables of age, sex, IQ, or social status, but rather the process variables that are essential to our theories. Including these process variables remains a challenge to differential psychology.

The principles of differential psychology are seen outside psychology in computer science simulations and games, in medical assessments of disease symptomatology, in college and university admissions, in high school and career counseling centers, as well as in applied decision-making.

Early Differential Psychology and Its Application

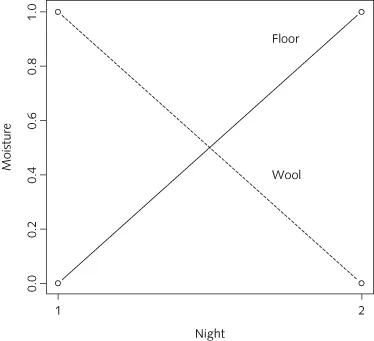

Differential psychology is not new; for an understanding of research methodology and individual differences in ability and affect was described as early as the Hebrew Bible, in the story of Gideon (Judges 6: 37–40, 7: 2–6). Gideon was something of a skeptic, who had impressive methodological sophistication. In perhaps the first published example of a repeated-measures crossover design, he applied several behavioral tests to God before agreeing to go off to fight the Midians, as he was instructed. Gideon put out a wool fleece on his threshing floor and first asked that by the next morning just the fleece should be wet with dew, but the floor should be left dry. Then, the next morning, after this happened, as a crossover control, he asked for the fleece to be dry and the floor wet. Observing this double dissociation, Gideon decided to follow God’s commands. We believe that this is the first published example of the convincing power of a crossover interaction. (See Figure 1.1, which has been reconstructed from the published data.)

Figure 1.1 Gideon’s double dissociation test. Gideon’s testing of God is an early example of a double dissociation test, and probably the first published example of a crossover interaction. On the first night, the wool was wet with dew but the floor was dry. On the second night, the floor was wet but the wool was dry (Judges 6: 36–40)

In addition to being an early methodologist, Gideon also pioneered the use of a sequential assessment battery. Leading a troop of 32,000 men to attack the Midians, Gideon was instructed to reduce the set to a more manageable number (for greater effect upon achieving victory). To select 300 men from 32,000, Gideon (again under instructions from God) used a two-part test. One part measured motivation and affect by selecting those 10,000 who were not afraid. The other measured crystallized intelligence, or at least battlefield experience, by selecting those 300 who did not lie down to drink water but rather lapped it with their hands (McPherson, 1901).

Gideon thus combined many of the skills of a differential psychologist. He was a methodologist versed in within-subject designs, a student of affect and behavior, and someone familiar with basic principles of assessment. Other early applications of psychological principles to warfare did not emphasize individual differences as much as the benefits of training troops in a phalanx (Thucydides, as cited by Driskell & Olmstead, 1989).

Personality Taxonomies

That people differ is obvious. How and why they differ is the subject of taxonomies of personality and other individual differences. An early and continuing application of these taxonomies is most clearly seen in the study of leadership effectiveness. Plato’s (429–347 BC) discussion of the personality and ability characteristics required of the hypothetical figure of the philosopher–king emphasized the multivariate problem of the rare co-occurrence of appropriate traits:

… quick intelligence, memory, sagacity, cleverness, and similar qualities, do not often grow together, and that persons who possess them and are at the same time high-spirited and magnanimous are not so constituted by nature as to live orderly and in a peaceful and settled manner; they are driven any way by their impulses, and all solid principle goes out of them. […] On the other hand, those steadfast natures which can better be depended upon, which in a battle are impregnable to fear and immovable, are equally immovable when there is anything to be learned; they are always in a torpid state, and are apt to yawn and go to sleep over any intellectual toil. […] And yet we were saying that both qualities were necessary in those to whom the higher education is to be imparted, and who are to share in any office or command.

(Plato, 1892: The republic, VI, 503c–e)

Similar work is now done by Robert Hogan and his colleagues as they study the determinants of leadership effectiveness in management settings (Hogan, 1994, 2007; R. Hogan, Raskin, & Fazzini, 1990; Padilla, Hogan, & Kaiser, 2007) as well as by one of the editors of this volume, Adrian Furnham (Furnham, 2005). The dark-side qualities discussed by Hogan could have been taken directly from The Republic.

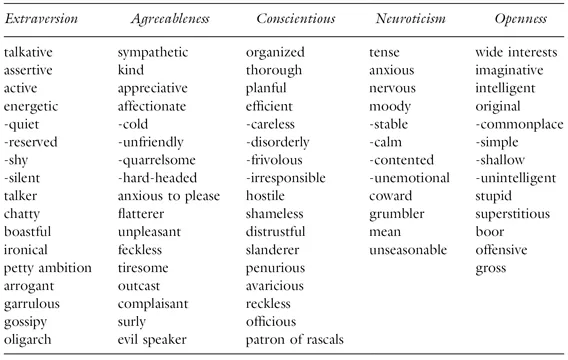

A typological rather than dimensional model of individual differences was developed by Theophrastus—or rather Tyrtamus of Eresos, in Lesbos (372–287 BC), a student of Aristotle who, according to his teacher, acquired the nickname “Theophrastus” (“the one who speaks like a god”) for his oratorical skills. Theophrastus is famous today as a botanical taxonomist. But he is also known to differential psychologists as a personality taxonomist, who organized the individual differences he observed into a descriptive taxonomy of “characters.” The Characters of Theophrastus is a work often used to illustrate and epitomize the lack of coherence of early personality trait description; however, it is possible to organize his “characters” into a table that looks remarkably similar to equivalent tables of the late twentieth century (John, 1990; John & Srivastava, 1999; see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Theophrastus’s character types and the traits of the “Big Five” show remarkable similarity. “Big Five” adjectives taken from John, 1990; Theophrastus’s Characters presented in Jebb’s translation of 1870

One thousand and six hundred years after Theophrastus, Chaucer added to the use of character description in his Canterbury Tales, which are certainly the first and probably the “best sequence of ‘Characters’ in English Literature” (Morley, 1891, p. 2). This tradition continued into the seventeenth century: the character writings of that period are a fascinating demonstration of the broad appeal of personality description and categorization (Morley, 1891).

Causal Theories

Theophrastus asked a fundamental question of personality theory, which is still of central concern to us in personality theory today:

Often before now have I applied my thoughts to the puzzling question—one, probably, which will puzzle me for ever—why it is that, while all Greece lies under the same sky and all the Greeks are educated alike, it has befallen us to have characters so variously constituted.

(Theophrastus, 1870: Characters, p. 77)

Table 1.2 Greek and Roman causal theory of personality

| Physiological basis | Temperament |

| Yellow bile | Choleric |

| Phlegm | Phlegmatic |

| Blood | Sanguine |

| Black bile | Melancholic |

This is, of course, the fundamental question asked today by differential psychologists who study behavior genetics (e.g. Bouchard, 1994, 2004) when they address the relative contribution of genes and of shared family environment as causes of behavior.

Biological personality models have also been with us for more than two millennia, through the work of Plato, Hippocrates, and, later on, Galen, all of which had a strong influence. Plato’s placement of the tripartite soul into the head, the heart, and the liver and his organization of it into reason, emotion, and desire remain a classic organization of the study of individual differences (Hilgard, 1980; Mayer, 2001; Revelle, 2007). Indeed, with the addition of behavior, the study of psychology may be said to be the study of affect (emotion), behavior, cognition (reason), and motivation (desire), as organized by Plato (but without the physical localization).

About 500 years later, the great doctor, pharmacologist, and physiologist Galen (AD 129–ca216) unified and systematized the earlier literature of the classical period, particularly the work of Plato and of the medical authors of the Hippocratic Corpus, when he described the causal basis of the four temperaments. His empirical work, based upon comparative neuroanatomy, aimed to provide support for Plato’s tripartite organization of soul into affect, cognition, and desire. Although current work does not use the same biological concepts, the search for a biological basis of individual differences continues to this day.

Eighteen centuries later, Wilhelm Wundt (1874, 1904) reorganized the Hippocratic–Galenic four temperaments into the two dimensional model later discussed by Hans Eysenck (1965, 1967) and Jan Strelau (1998).

Early Methodology

In addition to Gideon’s introduction of the crossover experiment, Plato introduced two important concepts, which would later find an important role in psychometrics and in the measurement of individual differences. Something similar to the modern concept of true score and to that of a distinction between observed and latent variables may be found in the celebrated “allegory of the cave” at the opening of Book VII of Plato’s Republic (VII, 514a ff.). For, just as the poor prisoners chained to the cave wall must interpret the world through the shadows cast on the wall, so must psychometricians interpret individual differences in observed score as reflecting latent differences in true score. Although shadow length can reflect differences in height, it can also reflect differences in distance from the light. For the individual differences specialist, making inferences about true score changes on the basis of observed score differences can be problematic. Consider the increases in observed IQ scores over time, reported by Flynn (1984, 1987, 2000), which are known as the “Flynn effect.” It may be asked, is the Flynn effect a real effect, and are people getting smarter, or are the IQ scores going up in a process equivalent to the change in shadow length in the cave, say, because of a change in position, but not one of height in the real world? This inferential problem is also seen in interpretations of fan-fold interactions as reflecting interactions at the latent level rather than merely at the observed level (Revelle, 2007).

Table 1.3 Wundt’s two-dimensional organization of the four temperaments

| Changeability | ||

| Excitability | Melancholic | Choleric |

| Phlegmatic | Sanguine | |

Differential Psychology in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries

Any discussion of differential psychology must include the amazing contributions of Sir Francis Galton. Apart from considering the hereditary basis of ability (Galton, 1865, 1892), describing the results of an introspective analysis of the complexity of his own thoughts (Galton, 1879), or introducing the lexical hypothesis, later made popular by Goldberg (1990), by searching the thesaurus for multiple examples of character (Galton, 1884), Galton also developed an index of correlation in terms of the product of ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise for The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Individual Differences

- Wiley-Blackwell Handbooks in Personality and Individual Differences

- Title page

- Copyright page

- List of Plates

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- List of Abbreviations

- Part I: Individual Differences An Up-to-Date Historical and Methodological Overview

- Part II: Intelligence and Personality Structure and Development

- Part III: Biological Causes of Individual Differences

- Part IV: Individual Differences and Real-World Outcomes

- Part V: Motivation and Vocational Interests

- Part VI: Competence beyond IQ

- Index

- Plates