![]()

1

Real Estate Development, Urban Design and the Tools Approach to Public Policy

Steve Tiesdell and David Adams

Introduction

Urban design and place-making involves two key challenges – the first involves recognising what makes ‘good’ urban design and what constitutes ‘better’ places. The second involves delivering good urban design and creating better places on the ground. The first challenge involves, inter alia, developing and reflecting on normative theory about what constitutes a ‘good’ place. The second challenge typically requires close engagement with the real estate development process. This book deliberately focuses on the role and significance of design in the real estate development process, on the decision-making of key development actors and on the relationship between developers and designers. Its overarching object is to explore how higher quality development and better places can be achieved in practice through public policy (i.e. by state actions). It does not, however, interrogate the meaning of higher quality development, or of better places, which have both been addressed at length elsewhere. Instead, for the purpose of analysis, we intend to set aside these issues and focus clearly on delivery. We therefore make the assumption that, in any particular circumstance, ‘higher quality’ and ‘better’ can be defined and agreed and, in turn, made the object of public policy and design processes.1 If we know – or think we know – what better places are, it then becomes essential to understand how best to achieve them.

Urban design can be considered a process of enabling better places for people than would otherwise be created – this is becoming more commonly referred to as ‘place-making’. In this study, the primary concern is with urban design as public policy (Barnett 1974; 1982), reflecting its increasing prominence as a policy area in the UK and in many other countries. Although, in the narrowest sense, public policy on urban design might be equated to a planning or zoning system, we see it as a much wider activity, encompassing a fuller spectrum of state activities.

Urban design can be understood as a direct design and as an indirect design activity. George (1997) termed these design activities first-order and second-order design. In first-order design, the urban designer is a direct designer or ‘author’ of the built environment or a component of it – that is, the designer of a building, a public space, a floorscape, street furniture, an urban event or festival etc – in other words, a relatively discrete ‘project’ of some sort.2 In second-order design, urban designers design the decision environments within which other development actors – developers, funders, sundry designers, surveyors etc – necessarily operate.3 Decision environments are typically designed by means of plans, strategies, frameworks etc, but also by deployment and modulation of incentives and disincentives, such as financial subsidies, discounted land or infrastructure provision. Generally (though not exclusively) undertaken by the public sector, second-order design is similar to planning and to governance.

Second-order urban design occurs before the design of the development proposal/project, and is both proactive and place-shaping. It shapes the design and development processes by creating a frame for acts of first-order design. By setting design constraints and potentials, second-order design can thus give public policymakers significant influence on first-order design.4

As a second-order design activity, urban design can be considered similar to much contemporary governmental practice in which, as (Salamon 2002: 15) suggests, public managers must devise incentive systems that obtain cooperation from actors over whom they have only limited control. Those who see governments as hierarchies believe that power flows downwards and outwards from the top or centre, and consider that policy decisions can be implemented through ‘command-and-control’. Increasingly, however, this is an outdated view of the relationship between policy and implementation. Instead, the contemporary focus is on the processes of governance, with network metaphors frequently employed to describe and explain the institutional structure and operation of governance systems. Seen as systems of interacting networks of state and non-state actors, power is diffuse, with all actors having some resources with which to bargain in pursuit of their own ends.

The concept of governance means that state actors must operate in new ways: rather than command-and-control, their primary operating mechanism becomes bargaining and negotiation: ‘Instead of issuing orders, public managers must learn how to create incentives for the outcomes they desire from actors over whom they have only imperfect control.’ (Salamon 2002: 15, emphasis added). Arguing that network governance shifts the emphasis in policy delivery from (direct) management to (indirect) enablement, Salamon (2002: 16–17) highlights three enablement skills:

(1) Activation skills – those required to activate the networks of state and non-state actors in order to address public problems.

(2) Orchestration skills – analogous to those required of a symphony conductor in getting a group of skilled musicians to perform a given work in harmony and on cue so that the result is a piece of music rather than a cacophony.

(3) Modulation skills – those required to manipulate rewards and penalties to elicit cooperative behaviour from interdependent actors.

This is highly significant for urban designers working in or for the public sector, because it closely resembles the task they face and, in turn, the skills they need.

Providing the context for the book, this chapter is in four main parts. The first explores the real estate development process. The second discusses opportunity space theory. The third introduces the tools approach in public policy, discusses urban design policy instruments and presents a new typology. The fourth part discusses developers’ decision environments, and then outlines the structure of the book.

Real estate development

The real estate development process is a production process that creates the built environment. Acting as a form of intervention, public policy is a means of managing – ‘steering’ – real estate development, in pursuit of policy-shaped, rather than merely market-led, outcomes. To operate effectively, such policies and policymakers must have knowledge of the real estate development process, the calculus of risk and reward that drives it, the interests of and constraints upon key development actors – developers, designers, landowners, investors etc – and, as explained later, the likely impact of policy instruments on key actors’ decision environments.

Real estate development is highly cyclical and volatile. The old adage of ‘location, location, location’ oversimplifies the factors that make a successful development: both the design quality of the product and the timing of delivery are now recognised as being equally important to development success as the right location (Adams & Tiesdell 2010). In recent years, the neat separation between public and private-sector development has also begun to break down: very few development projects occur entirely within the private sector, unmediated by any form of public regulation and intervention, and development is increasingly a process of co-production between public and private sectors.

State–market relations in real estate can be approached from various disciplinary perspectives. At a simple level, it is possible to identify the various tasks or events involved in the process of development and to pinpoint those occasions when state and market interact (Barrett et al. 1978). At a more advanced level, an agency-based form of analysis recognises the way in which important roles within the development process – landowner, developer, designer, financier and regulator etc – are played out by a range of people and organisations, sometimes separately and sometimes in combination. Such forms of analysis also begin to highlight the power relations involved in development, and to explain how these actors come together in complex networks to constitute and reconstitute the structural context within which development takes place (Doak & Karadimitriou 2007).

As previous reviews of models of the development process have shown (Gore & Nicholson 1991; Healey 1991), state–market relations in real estate are not the exclusive possession of economics, but have been addressed across the social sciences, showing that the real estate development process is not simply an economic process but is also highly social (Guy & Henneberry 2000; 2002a). As Michael Ball’s ‘structures of building provision model’ emphasises, development is a function of social relations specific to time and place involving a variety of key actors – landowners, investors, financiers, developers, builders, various professionals, politicians, consumers etc (Ball 1986; 1998). At the same time, the state – both local and national – is an important actor both in its own right and as a regulator of other actors. Ball stresses how these relations must be seen in terms of both their specific linkages – functional, historical, political, social and cultural – and their engagement with the broader structural elements of the political economy.

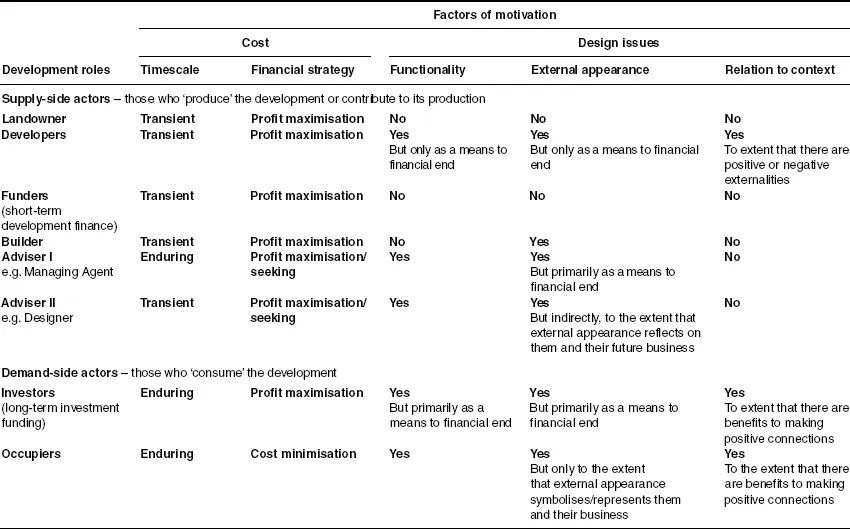

Actors become involved in development to the extent that it contributes to achieving their basic objectives. Table 1.1 examines the motives of the main actors in the development process in terms of five considerations – timescale, financial strategy, functionality, external appearance and relation to context. The nature of development means that these objectives are bundled, with each actor internally trading-off between objectives. The objectives are also traded-off between actors. The latter cannot be taken as an unproblematic process – actors have different strengths and powers, ‘quality’ may be interpreted differently and achieving ‘better’ design may not be an objective shared by all participants. Examination of Table 1.1, for example, indicates a mismatch between supply and demand sides. Supply-side actors typically have short-term, financial and economic motives and tend to see the development as a financial commodity. Demand-side actors typically have long-term and ‘design’ objectives and tend to see the development as an environment to be used.

Table 1.1 Motivation of development actors.

Source: Adapted from Carmona et al. 2003: 221; Tiesdell & Adams 2004.

The conflicting objectives of producer and consumer sides can lead to producer–consumer gaps. When traded-off between roles effectively played by a single actor (i.e. where a single actor is both ‘developer and funder’, or ‘funder, investor and occupier’), conflict over objectives is internalised, producing the most satisfactory outcome subject to budget constraints. When different actors’ objectives and motivations have to be reconciled externally (i.e. through market transactions), there is scope for significant mismatch or gaps between supply and demand. Development quality frequently falls through these producer–consumer gaps. Such gaps can be closed or narrowed in any of three main ways:

(1) Through regulation5 – developers ‘have-to’ provide better quality development.

(2) Through remunerative means – developers calculate that it is ‘worth-it’ (financially beneficial) to provide better-quality development.

(3) Through normative preferences – developers ‘want-to’ provide better quality development.

It is important to note that the first of these is coercive and the other two voluntary.

Closing producer–consumer gaps is a necessary but not sufficient condition of ‘good’ design. Responding to investors’ and occupiers’ needs, developers can exclude the general public’s needs. Segregated housing estates, gated communities and inward-focused developments, for example, provide what purchasers and occupiers purportedly want, but may contribute little to the wider public environment. The broader challenge is thus to encourage or compel developers to look across site boundaries, at their development’s impact on the wider context and, more generally, to contribute to making better places. Public intervention through judicious deployment of policy instruments might be a means of compelling or encouraging this.

Opportunity space theory

Drawing on Giddens’ structuration theory, Bentley (1999) argues that all development actors operate by rules and command ‘resources’ – finance, expertise, ideas, interpersonal skills etc – which other actors want and need. As Bentley argues, various webs of rules create ‘opportunity space’ – or scope for autonomous action – within which actors necessarily operate. The rules are internal (i.e. those actors place on themselves) and external (i.e. those placed upon them). For private developers, the external rules relate to budget constraints, appropriate rewards, the amount of risk to be incurred and the need to make a saleable product. Such rules are not arbitrary, cannot simply be ignored and are enforced through sanctions, such as bankruptcy. All development actors thus act within constraints – their opportunity space is not limitless but bounded.

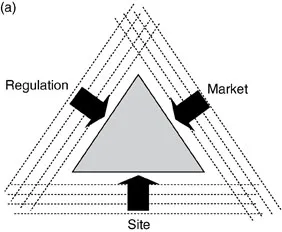

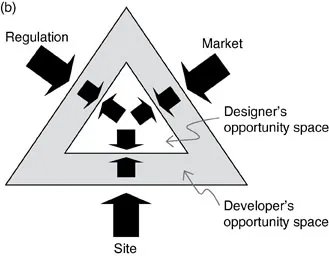

This is conceptualised in Figure 1.1a. Here, the developer’s opportunity space is substantially determined by three major external forces or contexts – the development site and its immediate context; the market context (e.g. the need to create a saleable product); and the regulatory context (e.g. the need for compliant development). The boundaries of the opportunity space are best conceived as fuzzy rather than hard-edged and ultimately depend on the respective negotiating abilities of the developme...

_fmt-plgo-compressed.webp)