eBook - ePub

Transplantation at a Glance

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Transplantation at a Glance

About this book

The first basic overview of all aspects of transplantation with a clarity not to be found in more inaccessible textbooks.

This brand new title provides a succinct overview of both the scientific and clinical principles of organ transplantation and the types of organ transplant, featuring highly-illustrated information covering core topics in transplantation including:

- Organ donors

- Organ preservation

- Assessment of transplant recipients

- Indications for transplantation

- Immunology of transplantation

- Immunosuppression and its complications

- Overviews of thoracic and abdominal organ transplantation, including the kidneys, liver, heart and lungs

Transplantation at a Glance is the ideal introduction for medical students, junior doctors, surgical trainees, immunology students, pharmacists, and nurses on transplant wards.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

History of Transplantation

Fundamentals

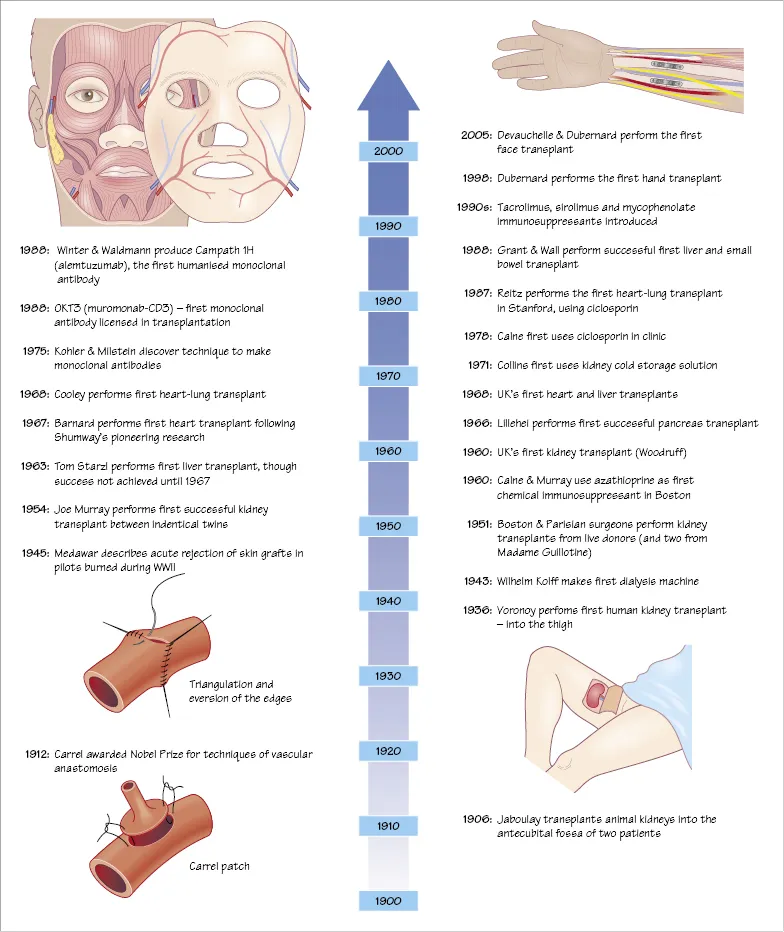

Vascular Anastomoses

Transplantation of any organ demands the ability to join blood vessels together without clot formation. Early attempts inverted the edges of the vessels, as is done in bowel surgery, and thrombosis was common. It wasn’t until the work of Jaboulay and Carrel that eversion of the edges was shown to overcome the early thrombotic problems, work that earned Alexis Carrel the Nobel Prize in 1912. Carrel also described two other techniques that are employed today, namely triangulation to avoid narrowing an anastomosis and the use of a patch of neighbouring vessel wall as a flange to facilitate sewing, now known as a Carrel patch.

Source of Organs

Having established how to perform the operation, the next step to advance transplantation was to find suitable organs. It was in the field of renal transplantation that progress was made, albeit slowly. In Vienna in 1902, Ulrich performed an experimental kidney transplant between dogs, and four years later in 1906, Jaboulay anastomosed animal kidneys to the brachial artery in the antecubital fossa of two patients with renal failure.

Clinical transplantation was attempted during the first half of the 20th century, but was restricted by an ignorance of the importance of minimising ischaemia – some of the early attempts used kidneys from cadavers several hours, and occasionally days, after death. It wasn’t until the mid-1950s that surgeons used ‘fresh’ organs, either from live patients who were having kidneys removed for transplantation or other reasons, or in Paris, from recently guillotined prisoners.

Where to Place the Kidney

Voronoy, a Russian surgeon in Kiev, is credited with the first human-to-human kidney transplant in 1936. He transplanted patients who had renal failure due to ingestion of mercuric chloride; the transplants never worked, in part because of the lengthy warm ischaemia of the kidneys (hours). Voronoy transplanted kidneys into the thigh, attracted by the easy exposure of the femoral vessels to which the renal vessels could be anastomosed. Hume, working in Boston in the early 1950s, also transplanted kidneys into the thigh, with the ureter opening on to the skin to allow ready observation of renal function. It was René Küss in Paris who, in 1951, placed the kidney intra-abdominally into the iliac fossa and established the technique used today for transplanting the kidney.

Early Transplants

The 1950s was the decade that saw kidney transplantation become a reality. The alternative, dialysis, was still in its infancy so the reward for a successful transplant was enormous. Pioneers in the US and Europe, principally in Boston and Paris, vied to perform the first long-term successful transplant, but although initial function was now being achieved with ‘fresh’ kidneys, they rarely lasted more than a few weeks. Carrel in 1914 recognised that the immune system, the ‘reaction of an organism against the foreign tissue’, was the only hurdle left to be surmounted. The breakthrough in clinical transplantation came in December 1954, when a team in Boston led by Joseph Murray performed a transplant between identical twins, so bypassing the immune system completely and demonstrating that long-term survival was possible. The kidney recipient, Richard Herrick, survived 8 years following the transplant, dying from recurrent disease; his twin brother Ronald died in 2011, 56 years later. This success was followed by more identical-twin transplants, with Woodruff performing the first in the UK in Edinburgh in 1960.

Development of Immunosuppression

Demonstration that good outcomes following kidney transplantation were achievable led to exploration of ways to enable transplants between non-identical individuals. Early efforts focused on total body irradiation, but the side effects were severe and long-term results poor. The anticancer drug 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) was shown by Calne to be immunosuppressive in dogs, but its toxicity led to the evaluation of its derivative, azathioprine. Azathioprine was used in clinical kidney transplantation in 1960 and, in combination with prednisolone, became the mainstay of immunosuppression until the 1980s, when ciclosporin was introduced. It was Roy Calne who was also responsible for the introduction of ciclosporin into clinical transplantation, the drug having originally been developed as an antifungal drug, but shelved by Sandoz, the pharmaceutical company involved, as ineffective. Jean Borel, working for Sandoz, had shown it to permit skin transplantation between mice, but Sandoz could foresee no use for such an agent. Calne confirmed the immunosuppressive properties of the drug in rodents, dogs and then humans. With ciclosporin, clinical transplantation was transformed. For the first time a powerful immunosuppressant with limited toxicity was available, and a drug that permitted successful non-renal transplantation.

Non-Renal Organ Transplants

Transplantation of non-renal organs is an order of magnitude more difficult than transplantation of the kidney; for liver, heart or lungs the patient’s own organs must first be removed before the new organs are transplanted; in kidney transplantation the native kidneys are usually left in situ.

After much pioneering experimental work by Norman Shumway to establish the operative technique, it was Christiaan Barnard who performed the first heart transplant in 1967 in South Africa. The following year the first heart was transplanted in the UK by Donald Ross, also a South African; and 1968 also saw Denton Cooley perform the first heart-lung transplant.

The first human liver transplantation was performed by Tom Starzl in Denver in 1963, the culmination of much experimental work. Roy Calne performed the first liver transplant in the UK, something that was lost in the press at the time, since Ross’s heart transplant was carried out on the same day.

Although short-term survival (days) was shown to be possible, it was not until the advent of ciclosporin that clinical heart, lung and liver transplantation became a realistic therapeutic option. The immunosuppressive requirements of intestinal transplants are an order of magnitude greater, and their success had to await the advent of tacrolimus.

In addition, it should be remembered that at the time the pioneers were operating there were no brainstem criteria for the diagnosis of death, and the circulation had stopped some time before the organs were removed for transplantation.

2

Diagnosis of Death and Its Physiology

Diagnosing Death

Circulatory Death

Traditionally, death has been certified by the absence of a circulation, usually taken as the point at which the heart stops beating. In the UK, current guidance suggests that death may be confirmed after 5 minutes of observation following cessation of cardiac function (e.g. absence of heart sounds, absence of palpable central pulse or asystole on a continuous electrocardiogram). Organ donation after circulatory death (DCD) may occur following confirmation that death has occurred (also called non-heart-beating donation).

There are two sorts of DCD donation, controlled and uncontrolled.

Controlled DCD donation occurs when life-sustaining treatment is withdrawn on an intensive therapy unit (ITU). This usually involves discontinuing inotropes and other medicines, and stopping ventilation. This is done with the transplant team ready in the operating theatre able to proceed with organ retrieval as soon as death is confirmed.

Uncontrolled DCD donation occurs when a patient is brought into hospital and, in spite of attempts at resuscitation, dies. Since such events are unpredictable a surgical team is seldom present or prepared, and longer periods of warm ischaemia occur (see later).

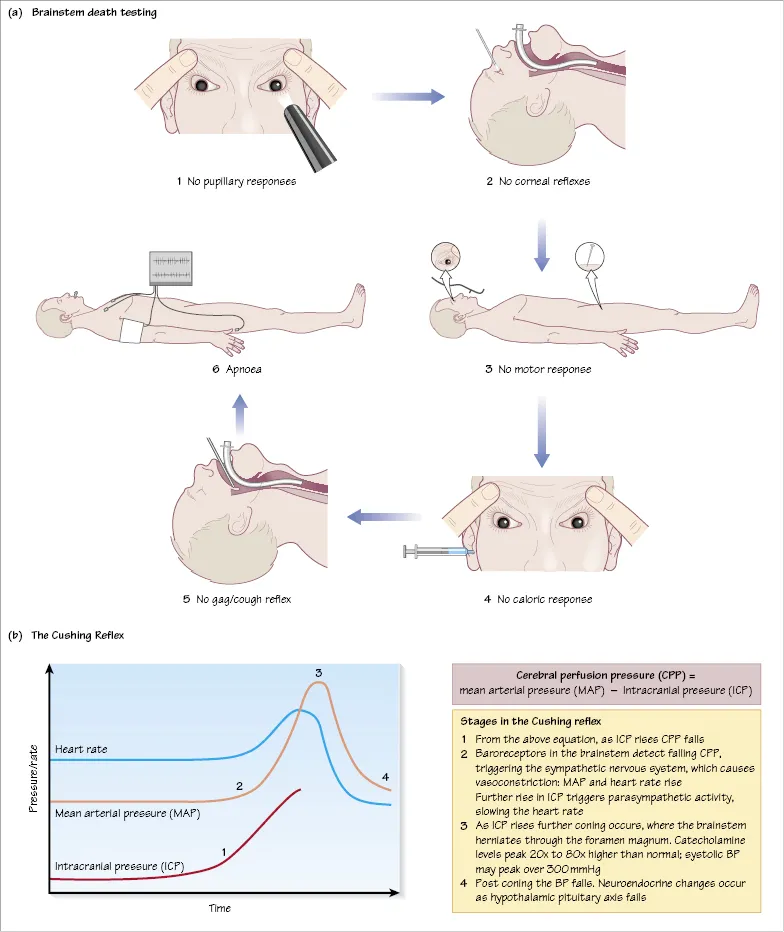

Brainstem Death

Brainstem death (often termed simply brain death) evolved not for the purposes of transplantation, but following technological advances in the 1960s and 1970s that enabled patients to be supported for long periods on a ventilator while deep in coma. There was a requirement to diagnose...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1 History of Transplantation

- 2 Diagnosis of Death and Its Physiology

- 3 Deceased Organ Donation

- 4 Live Donor Kidney Transplantation

- 5 Live Donor Liver Transplantation

- 6 Organ Preservation

- 7 Innate Immunity

- 8 Adaptive Immunity and Antigen Presentation

- 9 Humoral and Cellular Immunity

- 10 Tissue Typing and HLA Matching

- 11 Detecting HLA Antibodies

- 12 Antibody-Incompatible Transplantation

- 13 Organ Allocation

- 14 Immunosuppression: Induction vs Maintenance

- 15 Biological Agents

- 16 T Cell-Targeted Immunosuppression

- 17 Side Effects of Immunosuppressive Agents

- 18 Post-Transplant Infection

- 19 CMV Infection

- 20 Post-Transplant Malignancy

- 21 End-Stage Renal Failure

- 22 Complications of ESRF

- 23 Dialysis and Its Complications

- 24 Assessment for Kidney Transplantion

- 25 Kidney Transplantation: The Operation

- 26 Surgical Complications of Kidney Transplantation

- 27 Delayed Graft Function

- 28 Transplant Rejection

- 29 Chronic Renal Allograft Dysfunction

- 30 Transplantation for Diabetes Mellitus

- 31 Pancreas Transplantation

- 32 Islet Transplantation

- 33 Causes of Liver Failure

- 34 Assessment for Liver Transplantation

- 35 Liver Transplantation: The Operation

- 36 Complications of Liver Transplantation

- 37 Intestinal Failure and Assessment

- 38 Intestinal Transplantation

- 39 Assessment for Heart Transplantation

- 40 Heart Transplantation: The Operation

- 41 Complications of Heart Transplantation

- 42 Assessment for Lung Transplantation

- 43 Lung Transplantation: The Operation

- 44 Complications of Lung Transplantation

- 45 Composite Tissue Transplantation

- 46 Xenotransplantation

- Index

- End User License Agreement

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Transplantation at a Glance by Menna Clatworthy,Christopher Watson,Michael Allison,John Dark in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Surgery & Surgical Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.