eBook - ePub

The Ethnic Dimension in American History

James S. Olson, Heather Olson Beal

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Ethnic Dimension in American History

James S. Olson, Heather Olson Beal

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Ethnic Dimension in American History is a thorough survey of the role that ethnicity has played in shaping the history of the United States.

Considering ethnicity in terms of race, language, religion and national origin, this important text examines its effects on social relations, public policy and economic development.

- A thorough survey of the role that ethnicity has played in shaping the history of the United States, including the effects of ethnicity on social relations, public policy and economic development

- Includes histories of a wide range of ethnic groups including African Americans, Native Americans, Jews, Chinese, Europeans, Japanese, Muslims, Koreans, and Latinos

- Examines the interaction of ethnic groups with one another and the dynamic processes of acculturation, modernization, and assimilation; as well as the history of immigration

- Revised and updated material in the fourth edition reflects current thinking and recent history, bringing the story up to the present and including the impact of 9/11

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Ethnic Dimension in American History an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Ethnic Dimension in American History by James S. Olson, Heather Olson Beal in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire de l'Amérique du Nord. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Worlds Collide

Indian People, Africans, and Europeans in Colonial America

Indian People, Africans, and Europeans in Colonial America

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, political, economic, and religious upheavals disrupted the lives of millions of people in western Europe. Nation-states were emerging in Spain, Portugal, France, and England as local monarchs extended their territorial authority; entrepreneurs were searching for lucrative business opportunities; and rumblings of rebellion against the Catholic Church had been sounding for decades. The convergence of nationalism, the Commercial Revolution, and the Reformation shook Europe to its foundation and sent thousands of people across the Atlantic in search of economic opportunity and religious security.

North America’s first colonists had to cope not only with a harrowing ocean voyage and often hostile inhabitants but also with their own religious rivalries and political expectations. Virginia had its “starving time”; the Plymouth colonists braved a horrible winter in flimsy wooden huts; and New England shuddered in fear during King Philip’s War. Eventually the colonists adjusted to the environment, transforming scarcity into abundance, at least for white people. On the shores of the New World, colonial America played host to diversity and to its discontents.

Among European settlers, religious issues tended to shape debate about diversity. Compared with the rest of the world, British North America seemed an island of toleration in a vast sea of bigotry—even though Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Anglicans, and Catholics were hardly known for open-mindedness. Because America was settled by many groups, political loyalty was never identified with any one set of religious beliefs. To be sure, a powerful Protestant spirit thrived, but in the absence of a national church, American culture was nonsectarian. Love of country never implied love of a particular church.

Diversity led slowly to religious toleration. Jews, Catholics, Friends (Quakers), Separatists, Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Baptists, Methodists, Dutch Reformed, Lutherans, and German Reformed all competed for converts, but no single group enjoyed an absolute majority. All were minorities, and, to protect its own security, each had to guarantee the security of others. Tolerance evolved slowly, even torturously. Virginia prohibited Jewish immigration in 1607; Governor Peter Stuyvesant of New Netherland imposed discriminatory taxes on Jewish merchants in the 1650s; and Pennsylvania tried to prevent Jews from voting in 1690. The Maryland Toleration Act of 1649, which promised freedom of worship for all Christians, was temporarily repealed in 1654. Massachusetts expelled Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson for heresy in the 1630s and persecuted Quakers throughout the 1600s. Nor was any love lost between Anglicans and Scots-Irish Presbyterians in the South. Still, each denomination drifted toward toleration out of necessity, and crusades to win converts were largely voluntary affairs by the late 1700s. Freedom of religion only gradually became a hallmark of American democracy, more a product of migration than the cause of it.

As the colonists came to terms with diversity, they institutionalized the natural rights theory of John Locke—that governments were only temporary compacts protecting individual claims to life, liberty, and property. The colonists believed that power was evil, governments dangerous, and restrictions on political power absolutely necessary. Such basic concepts as separation of powers, checks and balances, federalism, and natural rights would eventually circumscribe power and exalt the individual rather than state or church; people of color, however, were systematically excluded from its embrace, as if they did not really exist, except to serve the needs of those in power.

The European colonists worshiped God in different ways but paid homage to themselves with remarkable consistency: they possessed “unalienable” rights, and the purpose of government was to sustain those rights. Early American politics inaugurated the first successful colonial rebellion in modern history. By 1776 the colonists had concluded that England was fulfilling Locke’s warnings about the dangers of concentrated political power. They considered writs of assistance, the Sugar Act of 1764, the Stamp Act of 1765, the Townshend Acts of 1767, the Tea Act of 1773, and the Intolerable Acts of 1774 to be violations of individual rights. Parliament had thereby surrendered its legitimacy as a government of the colonies. The Declaration of Independence and later the Constitution formally established natural rights as a basis for governance.

The colonial period, then, established as standards freedom of religion—with its implied respect for religious diversity—and the natural rights philosophy. Nothing would test those standards more severely than ethnic diversity. When nationalism gradually unified Americans politically, ethnic diversity divided them culturally. At the same time, the natural rights philosophy theoretically offered justice and equity to everyone. The tensions between ethnic diversity and egalitarianism would become the central dynamic in United States history.

During the colonial era, the processes of acculturation and assimilation went to work on the settlers and their descendants. Though closely related, acculturation and assimilation are hardly synonymous; the former is the process of acquiring a second culture, the latter, the act of substituting a second culture for one’s own. Both can consume decades and generations and are more likely to be developments, not events; in the United States, they have been conjoined and are often symbiotic. Acculturation and assimilation can be natural and evolutionary as well as coerced and heavy-handed matters of public policy. Advocates of whiteness theory also argue that acculturation and assimilation, even when apparently natural and invisible, can nevertheless reflect the demands of entrenched white interests.

During the nineteenth century, because of mass immigration from Europe, the United States became the scene of ethnic conflict and adaptation across a wide spectrum of color, religion, and national origin. Caught up in vast economic and social change, the young republic had to decide whether individual liberty applied to people of color as well as to members of every religion. The community horizons of early Protestants were challenged by profound ethnic differences. In the eighteenth century, cultural conflict had largely involved white Protestants, and freedom of religion had implied toleration for each Protestant denomination. But in the nineteenth century, Catholic immigration from Ireland, Germany, and Quebec concerned many Protestants, who had only recently learned to live with one another. At the same time, immigrants from various nations in Europe, for all of their linguistic and religious differences, broadly shared skin color and gradually made common cause in the presence of people of color, erecting a political and economic system that reserved the privileges of power and status to whites.

In recent decades, scholars have put under new and careful scrutiny many long-held, fixed classifications of race and have abandoned them as functional descriptions of biological reality. Studies of the human genome have detected no meaningful differences among individuals from different so-called racial groups, so “race” is now seen as a social construct, an invented reality that has insinuated itself into the institutional structures of society and has been employed by those in positions of authority to perpetuate their power. As legal scholar Ian F. Haney Lopez has written,

I define a “race” as a vast group of people loosely bound together by historically contingent, social significant elements of their morphology and/or ancestry. I argue that race must be understood as a … social phenomenon in which contested systems of meaning serve as the connections between physical features, races, and personal characteristics. In other words, social meanings connect our faces to our souls. Race is neither an essence nor an illusion, but rather an on-going, contradictory, self-reinforcing process subject to the macro forces of social and political struggle and the micro effects of daily decisions.1

Although no such thing as a “white race” exists genetically, some theorists consider “whiteness” a social construct that has muscled its way into forms of identity; into definitions of beauty, normalcy, and status; and into positions of political and economic power, even becoming a form of property entitling access to education, employment, and other forms of privilege while allocating social and economic resources “racially.” They see whiteness as a constant in United States history and as a powerful vehicle, consciously and unconsciously, in marginalizing people of color and denying them access to its attendant benefits.

Nineteenth-century European Americans invested a great deal of energy in defining what it meant to be white, and that definition became inextricably linked to the exercise of power. Early in the century, for example, many descendants of English, Scots, Scots Irish, Dutch, and German colonists, now embedded in the power structure, refused to accept Chinese immigrants and Irish Catholics as whites. Later in the century, they did the same to Roman Catholic, Jewish, and Eastern Orthodox immigrants from central, southern, and eastern Europe. Although definitions of whiteness eventually came to include immigrants from Ireland, central Europe, and eastern Europe, the process was tempestuous and sometimes violent.

Whites also had to determine whether people of color—African Americans, Native Americans, Mexican Americans, and Asian Americans—were entitled to freedom and equality; for the most part, they decided in the negative. Indian people had their land taken from them, as did Mexican Americans, and all people of color faced obstacles in exercising the right to vote and hold public office. Slavery had long rendered hollow the promise of equality and opportunity, and after the Civil War, in spite of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution, people of color spent more than a century trying to convert constitutional promises into political and economic reality; by the early twenty-first century, the fracture between the real and the ideal resembled chasm more than mere divide.

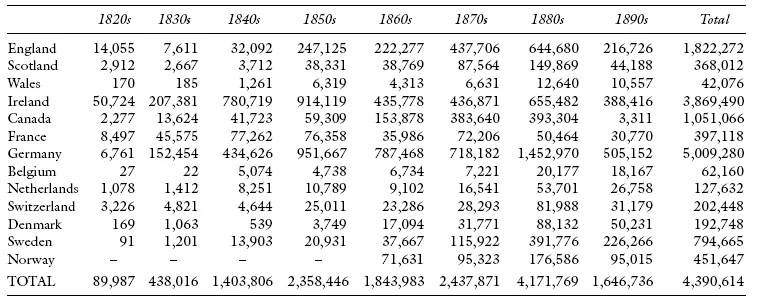

Economic change created new subcultures in the United States. The transition from a mercantile and subsistence-farming economy to industrial production, commercial farming, and resource extraction stimulated demand for land and labor, and millions of immigrants were drawn into that expanding economy. With jobs in the Northeast and land in the West, America seemed a beacon of opportunity, toleration, and freedom to small farmers and artisans in western Europe and southeastern China. Few social movements in modern history compare with what some historians label the “Great Migration”—the relocation of 18 million people to the United States between 1820 and 1900. The Great Migration, which resembled the eruption of a huge social volcano, transformed the human landscape throughout the Western world.

Economic unrest explains much of the immigration process. In medieval England, some land, though nominally owned by an individual, remained open to others for the purposes of grazing livestock, mowing hay, and farming. During the fifteenth century, however, it became more profitable to partition and fence (“enclose”) these common lands into multiple tracts, deed them to individuals, and prohibit use by others. The enclosure of land previously in common use displaced many families and prompted their immigration to the New World.

Other forces provoked immigration. Because of the smallpox vaccine, the introduction of the American potato, and the absence of protracted war, Europe’s population increased from 140 million in 1750 to more than 260 million in 1850 and nearly 400 million by World War I. Farm sizes dwindled, and many younger sons and laborers surrendered hope of ever owning their own land. As huge mechanized farms appeared in the United States and oceanic transportation improved, American wheat became competitive in European markets. World grain prices and the income of millions of small farmers declined. Except for the tragic potato blight in Ireland, these changes occurred little by little, year after year. To supplement their incomes, European farmers found extra work in the winter. Many traveled to cities—Bergen, Amsterdam, Christiania, Copenhagen, Hamburg, Bremen, Antwerp, Vienna, or Prague—to look for jobs and became a migrant people long before their arrival in the United States.

Table I.1 Immigration from Western Europe, 1820–1900*

*Annual Report, US Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1973.

Just as opportunities in agriculture diminished, changes in the industrial economy eliminated many traditional occupations. When cheap Canadian and American timber entered Europe in the nineteenth century many jobs in the lumber industries of Scandinavia and Germany disappeared. Shipbuilding in Canada and the United States eliminated more jobs in northern Europe. Factories supplanted production of goods by independent artisans. Working longer hours for less money to compete with the mass-produced goods of American, English, and German factories, many independent artisans grew dissatisfied with the present and anxious about the future. After the 1870s, millions of industrial workers immigrated to the United States looking for better jobs and higher wages. Except for the Irish, immigrants were not typically the most impoverished people of Europe; chronically unemployed members of the proletariat and peasants working large estates usually did not emigrate. Such a drastic move required both vision and resources. Status-conscious workers and small farmers traded Old World problems for New World opportunities.

Appetites whetted by the advertisements of railroads hungry for workers, steamship companies for passengers, and new states for settlers, they came from the British Isles, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Scandinavia, and China. The Irish left from Queenstown, in Cork Harbor, or crossed the Irish Sea on packet ships and departed from Liverpool; the Scots boarded immigrant vessels at Glasgow; the English and Welsh traveled by coach or rail to Liverpool and left from there; the Germans made their way to Antwerp, Bremen, or Hamburg; and the Scandinavians left first from Bergen, Christiania, or Goteborg for Liverpool, and from there sailed to America. Diseases in these sailing ships stole many lives. After weeks or months at sea in crowded holds, immigrants landed in the Maritime Provinces of Canada, Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, or New Orleans. From Canada they traveled down the St Lawrence to the Great Lakes or caught vessels to Boston; from the Atlantic ports most made rail, wagon, or steamboat connections to the interior; and from New Orleans they went up the Mississippi River and scattered out along its tributaries. The Chinese immigrants left from Canton, Hong Kong, and Macao, stopped over for a period in Hawaii, and sailed on to San Francisco.

Before 1890, most Protestant immigrants scattered widely throughout the country, getting jobs in the cities or building farms in the hinterland. Most Americans welcomed them, and they in turn embraced religious toleration, political liberty, and economic opportunity. On the other hand, the immigration of Irish, German, and French-Canadian Catholics, as well as Chinese Buddhists, tested the American commitment to pluralism. Themselves affected by dislocations of industrialization and mobility—and without the traditional moorings of a powerful central government, a state church, or extended kinship systems—millions of Americans obsessed about the Catholic influx. Rumors of papal conspiracies and priestly orgies became common, as did discrimination against Catholics. Chinese immigrants encountered similar fears. Few Americans had any idea of how to incorporate these immigrants into the society.

While the Great Migration generated cultural controversy, the westward movement created disputes involving Indians and Mexicans on the frontier. German, Scandinavian, English, and Scots-Irish farmers moved into the Ohio Valley, the southeastern forests, and west of the Mississippi. In the Treaty of Paris of 1783, ending the American Revolution, Britain ceded its land east of the Mississippi River, and in 1803 President Thomas Jefferson added the Louisiana Purchase. Spain sold Florida in 1819. Great Britain ceded all of Oregon below the 49th parallel in 1846; after the Mexican War, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo gave Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, California, Nevada, Utah, and part of Colorado and Wyoming to the United States. The American empire now stretched from ocean to ocean. Native Americans were pushed to the west and Mexicans with ancestral homes there had new difficulties. Both peoples faced the pressures of immigration of hundreds of thousands and eventually millions of whites. In the process, Mexican and Indian people saw their land taken. Their plight tested the reality of freedom and equality in American life.

Finally, Southern society confronted the natural rights philosophy. During the American Revolution, the hypocrisy of fighting for freedom while ignoring slavery was clear, and first in New England and then throughout the North slavery came under condemnation. Many Southerners began defending the peculiar institution as a positive good making possible an advanced stage of civilization for part of the population. There was little room for compromise because the economic and social imperatives of slavery—the need to control a large black population in order to exploit its involuntary labor—rendered natural rights irrelevant in most planters’ minds. During the Missouri debates of 1819 and 1820 regarding the status of slavery in territories, the North and South divided sharply over the question of slavery, especially its expansion west. The Liberty Party in 1840 and the Free-Soil Party in 1848 campaigned to keep slavery out of the West, while Southerners in the Democratic Party wanted desperately to see slavery expand. The sectional crisis deepened in the 1850s and then exploded into civil war.

Meanwhile, immigration was transforming the Northeast. In 1849, Protestant nativists organized the Supreme Order of the Star Spangled Banner, a secret society complete with oaths, signs, and ceremonial garb. Described as Know-Nothings because of their refusal to talk about their activities, they called for immigration restriction, strict naturalization laws, discrimination against Catholics, and exclusion of the Chinese. Renaming themselves the American Party in 1854, they organized politically and enjoyed some success in areas where Irish and German Catholic immigrants settled, taking control of the Massachusetts state government and winning many local elections throughout the Northeast. Other shifts in political loyalty occurred. Throughout the nineteenth century, poor immigrants were drawn to the Democratic Party—descended from Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party—because of its sympathy for working people. But because of the increasing numbers of Irish and German Catholics in the party during the 1850s many immigrant Protestants, especially the British and Scandinavians, began looking for a new political vehicle, particularly one that opposed slavery.

They found it when the Republican Party was formed in the 1850s. By supporting tariffs, a sound currency, a national bank, and internal improvements, the Republicans won the loyalty of conservative businessmen; by condemning slavery and opposing its expansion into the western territories, they were joined by abolitionists and Free-Soilers; by tacitly supporting stricter naturalization laws to keep new immigrants from voting, they gained the support of anti-Catholic nativists; and by calling for free homesteads in the public domain, they won the support of English, Scandinavian, Dutch, and German farmers in the Midwest. The Republican Party represented everything the South feared—abolition, free soil, a national bank, protective tariffs, and internal improvements, any or all of which might create an economic alliance between the North and the West. When Republican Abraham Lincoln won the election of 1860, the South panicked and seceded from the Union. The Civil War had begun.

For Northerners the Civil War became a crusade against slavery, a reaffirmation of the commitment to equality and toleration. The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments to the Constitution, and the Civil Rights Act of 1866 all extended political rights to African Americans. Political and social structures, however, reflected “whiteness”: Native Americans and Mexican Americans were losing their land; the Chinese were about to be excluded permanently from the United States; and with the end of Reconstruction in 1876, African Americans were consigned to a social and economic lower class seemingly for centuries. Still, the rhetoric of equality and individual rights survived the conflict, even if the task of making them a reality seemed as difficult as ever.

1 <http://academic.udayton.edu/race/01race/race.htm> accessed November 11, 2009.

1

The First Americans

Although small bands of Europeans or Asians may have crossed the oceans to the Americas, Native Americans, scholars argue, descended from Siberian hunters who migrated to North America many thousands of years ago. Between 40,000 and 32,000 BCE, an ice age froze up millions of cubic miles of ocean water, dropping sea levels by hundreds of feet. The shallow ocean floor of the Bering Sea surfaced, leaving a land bridge (called Beringia) more than a thousand miles wide connecting eastern Asia with Alaska. Vegetation grew on what had once been the ocean floor, and animals from Siberia and...