This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Life of William Shakespeare is a fascinating and wide-ranging exploration of Shakespeare's life and works focusing on oftern neglected literary and historical contexts: what Shakespeare read, who he worked with as an author and an actor, and how these various collaborations may have affected his writing.

- Written by an eminent Shakespearean scholar and experienced theatre reviewer

- Pays particular attention to Shakespeare's theatrical contemporaries and the ways in which they influenced his writing

- Offers an intriguing account of the life and work of the great poet-dramatist structured around the idea of memory

- Explores often neglected literary and historical contexts that illuminate Shakespeare's life and works

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Life of William Shakespeare by Lois Potter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism of Shakespeare. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

“Born into the World”

1564–1571

A woman when she travaileth hath sorrow, because her hour is come. But as soon as she is delivered of the child, she remembereth no more the anguish for joy that a man is born into the world.

(John 16: 21, from the Gospel lesson for 26 April 1564, Book of Common Prayer 1559)

Birth and Baptism

The Stratford-upon-Avon parish register states that William Shakespeare was baptized into the Church of England on Wednesday 26 April 1564. The register does not give his date of birth, and it does not show how committed his parents were to the church into which they brought him, one that would have been heretical only six years earlier. The Book of Common Prayer does, however, give the words that would have been read on the occasion. Some of them appear above as the epigraph to this chapter.

The children baptized on the 26th would have been those born between the 22nd and the 25th, if they were considered strong enough to be brought to church. Traditionally, Shakespeare's birthday has been 23 April, which was the feast of St. George, the patron saint of England. A major holiday after 1415 (the year of Henry V's victory at Agincourt), St. George's Day was once celebrated with pageants depicting his most famous act, the killing of a dragon. For the select few belonging to the Order of the Garter it was an important feast, at which their attendance was required. St. George was the Red Cross Knight of Spenser's Faerie Queene and his red cross on a white background is the official flag of England. He is now considered a mythical figure, and when 23 April is celebrated it is because of Shakespeare, who sometimes seems almost equally mythical.

It is natural to be suspicious of the too convenient link between national poet and national saint, especially since 23 April is also the day on which Shakespeare died in 1616. Still, it may well be right. In the sixteenth century, Catholics and some Protestants believed that infants who died unbaptized could not go to heaven, so clergymen were supposed to warn parents to perform the ceremony no later than “the Sunday or other holy day next after the child be born.”1 The Sunday before the 26th was 23 April. The next holy day, Tuesday 25 April, was the feast of St. Mark, which had the reputation of being unlucky.2 There may have been another reason why it was not chosen. Since the minister was required to use the Book of Common Prayer, finalized in 1559, the congregation on St. Mark's day would have heard a Gospel reading in which Jesus tells his disciples that “If a man bide not in me, he is cast forth as a branch, and is withered. And men gather them, and cast them in the fire, and they burn” (John 15: 5–6).3 This reading would have been particularly divisive in 1564, only a year after the publication of John Foxe's Acts and Monuments (usually called “Foxe's Book of Martyrs”), with its vivid woodcuts of Protestants being burned at the stake by Catholics. It was a time when many still remembered those on both sides who had been burned for their faith.

John Bretchgirdle, vicar of Stratford for the past three years, had every reason to be tactful. When Elizabeth I succeeded her sister Mary in November 1558, the incumbent Catholic vicar refused either to conform to the Protestant religion or to resign from his post, so the Corporation of Stratford forced him out by withholding his salary. His departure left the town with no resident clergyman for some time. The local congregation must have been divided and perhaps resentful. Bretchgirdle, an unmarried man with an Oxford MA, was the kind of well-educated preacher that the Reformation leaders wanted to establish in every parish, and would not have offended those who disapproved of married clergy. He died only a year after this christening, requesting in his will that his possessions should be sold, and the proceeds given to various charities.4 This learned and charitable man was no doubt perfectly capable of gloating over the burning of those outside the true faith. Still, he does not sound like someone who would provoke his congregation by baptizing the son of a leading citizen on a day when the readings were bound to antagonize supporters of the old religion. He had some reason to like the baby's father in any case: as chamberlain or acting chamberlain of Stratford-upon-Avon from 1561 to 1565, John Shakespeare had been heavily involved with maintenance and improvement of Corporation buildings, including the vicar's house.5 Bretchgirdle might also have felt sympathy for a man about to witness the baptism of his first son after losing his first two children in infancy.

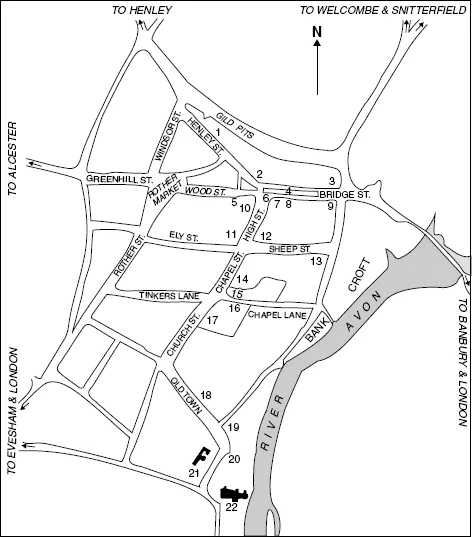

So it was on 26 April, at the end of either morning or evening prayer, that the baptismal party gathered round the font. It was probably the midwife who held the baby.6 Mary Shakespeare would be confined to her house for about a month, and then, in a special ceremony known as the Churching of Women, would come to the church to give thanks for a safe delivery and present the “chrisom” cloth in which the child had been wrapped, along with a sum of money. The Prayer Book put the desire for baptism into the mouth of the baby's godfather, who said, on its behalf, that he renounced the world, the flesh, and the devil with all his works, that he believed in all the articles of the Creed, and that he wished to be baptized in that faith. It was to the godparents that the priest directed his questions; until 1552 the child had been questioned directly, though someone else gave its answers, a kind of play-acting of which the Reformers disapproved.7 The godparents' task was to name the child, though they had probably discussed the choice with the parents. John and Mary Shakespeare did not give their own names to any of their children. A child was often named after a godparent, someone trusted by the parents and perhaps someone they hoped would be of financial as well as moral help. Possible godfathers include William Smith, a haberdasher who lived, like the Shakespeares, in Henley Street, and served on the town council alongside John Shakespeare,8 and William Tyler, a butcher in Sheep Street (John Shakespeare was a glover, and butchers provided the hides that glovers used).9 William may even have been named after a relation, if William Shakespeare of Snitterfield, mentioned in a document of December 1569, was an otherwise unknown brother of John Shakespeare.10 As the map (Figure 1) shows, the church was at the far end of town from the Shakespeares' house, and from most Stratford residents.

Figure 1 Elizabethan-Jacobean Stratford-upon-Avon 1. Two of John Shakespeare's houses (WS was probably born in one of them). JS also owned rental property in Greenhill St. 2. Bridge Street. House of Henry Field, tanner, father of the printer Richard Field 3. Swan Inn. This, and the Bear Inn across the street, are where prestigious guests were entertained. Its owner, Thomas Dixon/Waterman, a glover, may have been JS's master 4. Middle Row, where most shops were located 5. Wood Street, where Richard Hill and Abraham Sturley lived 6. High Cross, where markets were held 7. The Cage, a former prison, now a house; home, after 1616, of Thomas and Judith Quiney 8. Crown Inn 9. Bear Inn 10. High Street, where the Quiney family lived 11. House of Thomas Rogers (butcher): now called Harvard House after his grandson John Harvard 12. House of Roger Sadler (baker), then of Hamnet and Judith Sadler 13. House of William Tyler (butcher) 14. House of July Shaw (later witness of WS's will) 15. New Place 16. Guild Chapel 17. Guild Hall and grammar school 18. Hall's Croft, possible residence of John and Susanna Hall from 1608 to 1616 (though they may have lived continuously at New Place) 19. House of William Reynolds, one of WS's legatees 20. Thomas Greene, town clerk of Stratford, lived here from 1612 to 1616, after moving out of New Place 21. The College, formerly a religious institution, then the Stratford home of Thomas Combe, father of William and Thomas, WS's friends 22. Holy Trinity Church, where the Shakespeare family are buried

The relatives of the parents probably attended as well. John's father had died in 1561, but Henry Shakespeare, John's one identifiable brother, lived in the next village. Mary Shakespeare's relatives were more numerous. She was born Mary Arden, a family name derived from the forest of Arden, which contains the villages in which all the pre-1500 Shakespeares lived.11 Her father Robert had recently died, but she had numerous siblings from her father's two, or possibly three, marriages. Robert Arden had owned the land that John's father had farmed, so the Shakespeares and Ardens must have seen something of each other while Mary was growing up. When Robert Arden made his will he may well have known and approved of the impending marriage between his daughter and his ex-tenant's son. Among Mary's siblings, her sister Joan and Joan's husband Edmund Lambert are the most likely to have attended this baptism. All the Shakespeare daughters were named after Mary's sisters, but Joan's name was reused for a younger girl after an older one died, so the family must have felt particularly close to her.

The group may have included colleagues, friends, and neighbors, since by 1564 John Shakespeare had lived in Henley Street for at least ten years and was a member of Stratford's governing body. Those most likely to come were this year's bailiff, George Whateley, also of Henley Street, and his chief alderman, Roger Sadler of Church Street. Some of the twenty-seven other councilors might also have found time to attend the baptismal service, particularly Adrian Quiney, who had already served as bailiff of Stratford and would do so on two more occasions. He lived in the High Street, round the corner from John Shakespeare's house, and their two families would be closely connected for over fifty years.

A healthy child was dipped in the holy water, while a sickly one might be gently sprinkled on the head. The heavy font cover was designed to prevent people from stealing the water, which was normally replenished and blessed at Easter in Catholic times. Health-conscious parishes changed the water regularly; perhaps a child born three weeks after Easter – it fell on 2 April in 1564 – had an advantage in being exposed to relatively fresh water. Bretchgirdle probably made the sign of the cross on the child's forehead, to show that William was not ashamed of the faith of the crucified Christ; this was a controversial gesture, a relic of Catholicism, and some parents refused to allow it. The priest then exhorted the godparents to teach the Creed, the Lord's Prayer, and the Ten Commandments in English as soon as the child was capable of learning them, and the group went back to Henley Street for a celebratory feast. Some guests would have visited the child's mother, who was supposed to remain in a quiet, dark room for several days after giving birth. They brought her their christening gifts, usually silver spoons or, from the more affluent, pieces of plate.12 Sometimes these celebrations became rowdy....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Blackwell Critical Biographies

- Title Page

- Copyright

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- The Shakespeare Family Tree

- Chapter 1: “Born into the World”: 1564–1571

- Chapter 2: “Nemo Sibi Nascitur”: 1571–1578

- Chapter 3: “Hic et Ubique”: 1578–1588

- Chapter 4: “This Man's Art and That Man's Scope”: 1588–1592

- Chapter 5: “Tigers' Hearts”: 1592–1593

- Chapter 6: “The Dangerous Year”: 1593–1594

- Chapter 7: “Our Usual Manager of Mirth”: 1594–1595

- Chapter 8: “The Strong'st and Surest Way to Get”: Histories, 1595–1596

- Chapter 9: “When Love Speaks”: Tragedy and Comedy, 1595–1596

- Chapter 10: “You Had a Father; Let Your Son Say So”: 1596–1598

- Chapter 11: “Unworthy Scaffold”: 1598–1599

- Chapter 12: “These Words Are Not Mine”: 1599–1601

- Chapter 13: “Looking Before and After”: 1600–1603

- Chapter 14: “This Most Balmy Time”: 1603–1605

- Chapter 15: “Past the Size of Dreaming”: 1606–1609

- Chapter 16: “Like an Old Tale”: 1609–1611

- Chapter 17: “The Second Burden”: 1612–1616

- Chapter 18: “In the Mouths of Men”: 1616 and After

- Bibliography

- Index