- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Acute and Critical Care Medicine at a Glance

About This Book

The at a Glance series is popular among medical students and junior doctors for its concise and simple approach and excellent illustrations.

Each bite-sized chapter is covered in a double-page spread with colour summary diagrams on the left page and explanatory text on the right. Covering a wide range of topics, books in the at a Glance series are ideal as introductory subject texts or for revision purposes, and are useful throughout medical school and beyond.

Everything you need to know about Acute and Critical Care Medicine... at a Glance!

Following the familiar, easy-to-use at a Glance format, and now in full-colour, Acute and Critical Care Medicine at a Glance is an accessible introduction and revision text for medical students. Fully revised and updated to reflect changes to the content and assessment methods used by medical schools, this at a Glance provides a user-friendly overview of Acute and Critical Care Medicine to encapsulate all that the student needs to know.

This new edition of Acute and Critical Care Medicine at a Glance:

- Provides a brief and straightforward, yet rapid, introduction to care of the critically ill that can be easily assimilated prior to starting a new job or clinical attachment

- Encompasses the clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic skills required to manage acutely ill patients in a variety of settings

- Includes assessment of the acutely unwell patient, monitoring, emergency resuscitation, oxygenation, circulatory support, methods of ventilation and management of a wide variety of medical and surgical emergencies

- Includes new chapters on fluid management, oxygenation, non-invasive ventilation, recognition of the seriously ill patient and hospital-acquired infections

This book is an invaluable resource for all undergraduates in medicine, as well as clinical medical students, junior doctors, nurses caring for acutely-ill patients and paramedics.

Pre-publication reviews:

"The material forms an excellent basis for junior doctors in critical care and anaesthesia to get a good grounding in the subject, without appearing too scary."

– Senior House Officer

"The system-based approach...provides excellent reference material when studying a particular subject, allowing the reader to easily delve into the book when necessary, without having to read from cover-to-cover. It is an excellent revision aid.... Much time has gone into eliminating superfluous data so maximal essential information can be conveyed quickly."

– UCL student

Frequently asked questions

Information

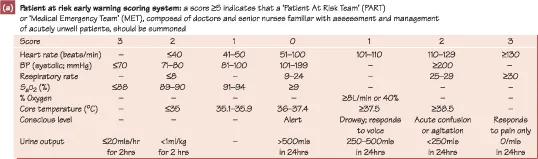

1 Recognizing the unwell patient

Recognizing the Acutely Unwell Patient

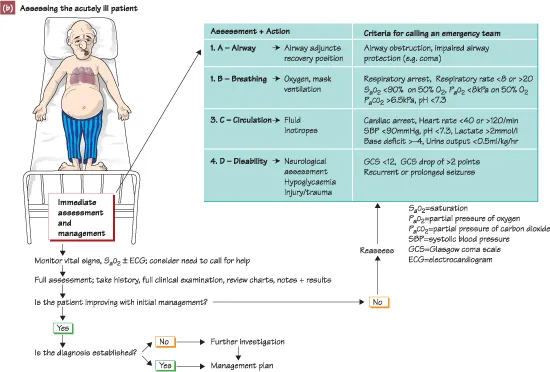

Assessment of the Acutely Ill Patient

2 Admission and ongoing management of

the acutely unwell patient

Organization

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Units, symbols and a bbreviations

- Part 1 - General

- Part 2 - Medical

- Part 3 - Surgical

- Part 4 - Self-assessment

- Appendices

- Index