![]()

Chapter 1

The Long Perspective

The terms ‘narrative’ and ‘architecture’ may not at first seem to be natural bedfellows. In today’s sense they suffer from slightly oppositional problems: the former proliferated and diluted, the latter restricted and reduced. In the media, reference to ‘narrative’ is now so commonplace as to evade meaning. In its tightest form it indicates a literary sensibility, but often dissolves simply into an ‘idea’. In the communication age, narration invades the everyday: ‘What’s happening?’ is a question answered by every tweet on Twitter.

Much 20th-century architecture pursued an abstract aesthetic that married well with functional ideals. Modernism celebrated the fact that it had broken free from the ‘tyranny’ of decoration. And yet despite this, the built environment inevitably ‘communicates’ – it cannot avoid doing so. Like nature the city can speak primordially, its fabric tacitly conveying its rich and potent history. A financial centre – the City of London, or New York – expresses its economic power through its glossy tallness as much as derelict buildings disclose their story of decline.

And we have stories of our own; the curious citizen can easily discover architectural narrative everywhere. Narratives arise spontaneously in the course of navigating the world – from inside to outside, private to public, personal experience to collective myth. This reading of architecture doesn’t require an architect to have ‘written’ it. Even unplanned settlements such as shantytowns or medieval villages contain complex narrative content; for an inhabitant they will configure a three-dimensional map of social relations, possible dangers and past events. Mental maps situate fragments in a time–space continuum: a house where you once lived, or the scene of an accident. The city constitutes a rich theatre of memory that melds all the senses in ways that suit every single one of us, in our capacity to combine instinct and knowledge, rational understanding and the imagination.

Personal narratives build on the cognitive mechanisms that arise from existing places and spaces. Narrative has its roots in the world we inhabit, and occurs at the interface between our own experience and complex signs, like the little red pointers that smother other data on Google maps. It does not necessarily manifest as appearance; the fields in Flanders where so many First World War battles took place have an emotional significance as a site of loss but today look much like any other. We are walking encyclopaedias of architecture not because we’ve shaped it, but because we experience it.

This chapter asks how narrative applies to architecture. We shall see how narrative in space as opposed to literature or cinema has a firm basis in the way each of us learns to navigate and map the world around us. Within the framework of these personal spatial geometries, we will explore how narrative constructs can engage with the medium of space. This will provide a framework for how architecture can be invested with narrative as a means to give it meaning based on experience.

Narrative: from storytelling to spatial practice

Storytelling is as old as the hills. Even before the help of writing, universal myths were shaped by the oral tradition. From the Songlines of the Australian Aboriginals to the proto-myths of the Greeks, mankind has searched for answers to the mysteries of the universe, painting them on walls and encapsulating them in stories. Narratives enabled phenomena powered by the unseen forces of nature to be ‘explained’, and corralled into a system of beliefs. Their overarching themes lie at the heart of the major religions. Narratives that personify ethical or existential questions have profoundly shaped our understanding of space; these mythical tales and parables have the power to mediate between the spatial configuration of the universe, of heaven and hell, and the everyday world and its reality of survival, sustenance and territory. Within the framework of these spatial geometries, narratives can engage with the medium of space, and form the basis on which architecture can be given meaning.

With roots in the Latin verb ‘narrare’, a narrative organises events of a real or fictional nature into a sequence recounted by the ‘narrator’. Along with exposition, argumentation and description, narration is one of four categories of rhetoric. The constructed format of a narrative can extend beyond speech to poetry, singing, writing, drama, cinema and games. Narration shapes and simplifies events into a sequence that can stimulate the imagination, and with its understanding comes the possibility of the story being retold – verbally, pictorially or spatially. Though they may involve shifts of time, location and circumstance as the dynamics of a plot unfold, for the viewer or the reader, stories progress along a sequential trajectory.

In architecture the linearity of the narrative function dissolves as the spatial dimension interferes with time. In architectural space coherent plot lines or prescribed experiential sequences are unusual. The narrative approach depends on a parallel code that adds depth to the basic architectural language. In a conventional narrative structure, events unfold in relation to a temporal metre, but in architecture the time element is always shifting in response to the immutability of the physical structure. While permanence should be celebrated as a particularly architectural quality, inevitably we should be curious about its opposite. The difference between a mere image and a work of art lies partly in its endurance – of existence but also of meaning. In architecture, that endurance is both positive and negative, depending on whether the public buys into it or not.

The various physical parts of a space signify as a result of the actions – and experiences – of the participant, who assembles them into a personal construct. The narrative coefficient resides in a system of triggers that signify poetically, above and in addition to functionality. Narrative means that the object contains some ‘other’ existence in parallel with its function. This object has been invested with a fictional plane of signification that renders it fugitive, mercurial and subject to interpretation. If a conventional narrative in a work of fiction binds characters, events and places within an overarching plot framework, in an environment narrative carries all of the above, but the fictional or self-constructed might be tested against physical reality. Narrative ‘fictionalises’ our surroundings in an accentuation of explicit ‘reality’.

Like the system of trip wires and pressure-sensitive buttons hidden in the folds of a Baroque fountain, narrative in architecture is rarely a prescribed sequence of meanings, but is instead an anti-sequential ‘framework’ of associative meanings held in wait to ‘drench’ the unsuspecting visitor. In whatever form, it communicates subtly and unpredictably, and often works better when hidden rather than overt. In a physical environment, narrative construes what philosopher and novelist Umberto Eco (b 1932) calls a ‘connotative’ rather than a ‘denotive’ meaning that is close to function. The temple represents the god it houses rather than the denotive meaning of the act of worship.1 In a world of postmodern, post-Structuralist understanding, the term ‘narrative’ has come to signify a level of meaning that substantiates the object, and yet contains an animated inner quality that interprets human events in relation to place.

The beginnings of architecture have been variously interpreted as the primitive hut,2 or – according to Eco – the recognition that a cave can provide protection and shelter.3 By the time the cave or the hut had fully formed as concepts, they must have featured as anecdotal homes. Myths and religions alike narrate the origin of the world in terms of everyday phenomena: in light and dark, in landscape and animals, and in men with supernatural powers. Since architecture can be manipulated and interpreted through narrative, it follows that the architect can invest architecture with a proportion of narrative alongside a response to the context and the programme of activities. Ancient temples of course tell stories, or highlights from them, as any visitor to the Louvre or the British Museum will appreciate.

Indeed, it is buildings that need the most potent symbolic content which make the most use of narrative strategies. Churches accumulate narrative as a result of the desire to reflect the story of God in every way possible, including the configuring of the body of Christ in their plan, their decoration, painting and sculpture. Northern Europe’s great medieval cathedrals also tell complex stories of configuration, veneration and extremes of heaven and hell. With the help of the pointed arch, the multiple column and the flying buttress, every Gothic cathedral exhibits a rational organisation of the world through its geometry and, with its enormous soaring windows, the ‘light of heaven’. Every aspect of these buildings has symbolic purpose, from the cruciform plan to details of capitals and windows.

Despite architecture usually being thought of as the art of articulating spaces, connotative meanings abound in its multi-various territories, and have done so from the outset. In architecture, narrative is a term that has risen in usage since the mid-1980s, but to grasp its implications, it would be valuable to visit some examples drawn from disconnected historical and physical contexts. What follows is distinctly not a history but a series of vignettes drawn from diverse times and places that together help define a context for narrative in architecture as an approach to practice. They are separated into the three gestalts; each one reveals narrative as the translation of a narrative spirit into a tangible, physical form.

Narrative awakenings

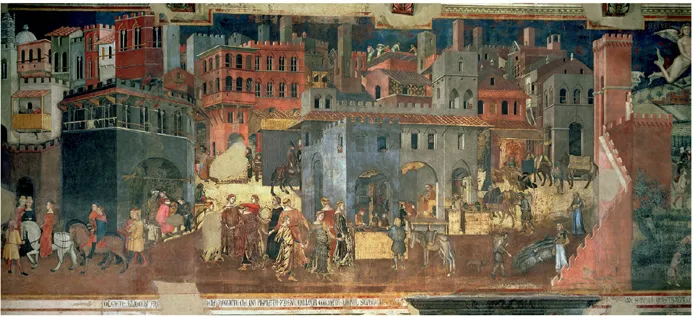

In the Palazzo Pubblico, the town hall of Siena in Italy, there is a frescoed state room that celebrates the relationship between the populus and its government, as had been expressed in the writings of contemporary chronicler Dino Compagni (c 1255–1324). The cycle of frescoes, The Allegory and Effects of Good and Bad Government, was painted by Ambrogio Lorenzetti (c 1290–1348) in the mid-14th century at a time when there was a need to stabilise civic ambitions. These two paintings representing good and bad face each other on opposite walls.

In the Allegory of Good Government everyday life is portrayed as a set of events occurring simultaneously. Unlike the extraordinary, usually religious occurrences represented in most painting of the period, this is an everyday scene with no apparent mishaps or strife. A narrative dimension builds on the commonplace. As opposed to blueprints of the architectural kind, in the painting the buildings constitute a backdrop, and in many ways their purpose was exactly that – a naturalistic mise en scène for the families that lived, and hopefully flourished, in and between them. On the opposite wall, the Effects of Bad Government includes decaying buildings, burning and a lot of cloak-and-dagger stuff. The painter’s use of the whole room as a conceptual matrix reinforces this dialogue between good and bad. Although flattened by its blocked representational technique, the sense of space in these frescoes is palpable, with people in the foreground and buildings and towers in a very three-dimensional middle distance. Despite the absence of precise architectural representation, Lorenzetti employed a plausible vocabulary of building types. You can sense the narrow alleyways between the buildings, reinforcing what you might experience when walking back through the city. This room establishes a thoroughly accurate ‘narrative’ that has relevance today.

In mid-15th-century Florence, Giovanni Rucellai, head of a prominent wool merchant family, commissioned Leon Battista Alberti (1404–72), the leading exponent of the classical revival that came to be known as the Renaissance, to build a palace where, according to Rucellai’s testimonial, ‘out of eight houses, I made one’.4 Alberti and his contemporaries were experimenting with building in the style of earlier, more poignant classical models. His design for the Palazzo Rucellai (1446–51) took its cue for the treatment of the orders of its pilasters from the Coliseum in Rome, with Tuscan capitals on the ground floor, Ionic on the first floor and Corinthian on the second. Rediscovered classicism was at the cutting edge of contemporary thinking to the extent of obsession and bitter rivalry.