![]()

Chapter 1

It’s the Deficit, Stupid

It is common knowledge that the United States owes a lot of money and that our debt is growing. No arguments about that. Where the debate starts and ends is how we are going to manage our debt. Will we be able to repay it? Will we choke on it? Or perhaps we will grow out of it and move into a surplus, much like we did during the Clinton administration.

First, the simple answer: The mounting U.S. deficit, i.e., the amount we spend over and above what we take in revenue and taxes, is a major problem that will result in a financial calamity soon. How soon? We don’t know, but soon enough that we need to be prepared for it. Politicians often rail about the massive federal debt we are leaving to our children and our grandchildren. They are right about the debt and wrong about the timing. Our children and grandchildren will not have to deal with the problem; we will! The crisis is approaching at alarming speed, and that is what this book is about.

Let’s back those statements up with some facts. Here again, we want to be conscious of the difference between epistemic humility and epistemic arrogance. Epistemology is a branch of philosophy that is about the study of knowledge. In our book, we try to distinguish between what is knowable and what isn’t. The future by its nature is not knowable, but some things are easier to predict than others. Linear events are easier to predict than random events, which are unpredictable. For example, if you have a stack of books and you add a new book to the stack every day, it is fairly easy to predict how high your stack will be a month from now. As you read this book, we want to make the case that our predictions are solidly grounded. This will constitute epistemic humility. Epistemic arrogance, on the other hand, is to us the practice of predicting events that are not supported by existing facts or trends. That would indeed be epistemic arrogance.

It would be arrogant to proclaim exactly when our rising national debt will turn into a financial debacle and a stock market crash, but it will likely occur sooner than we think. The national debt consists of all of the securities, bonds, notes, and bills issued by the United States Treasury. As of December 31, 2010, the “total public debt outstanding” of $14.03 trillion was approximately 94 percent of annual gross domestic product (GDP) of $14.9 trillion.1

How High the Debt?

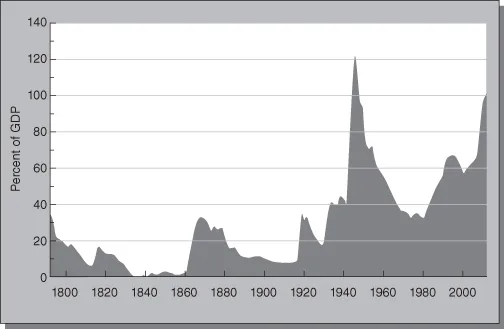

If today’s national debt is at a scary high of nearly 100 percent of GDP, how does that compare to the levels of debt in our nation’s history? As Figure 1.1 shows, we have come this close only once in the past. During World War II, the debt reached 120 percent of GDP. The debt was, of course, the result of the massive cost of World War II, and we spent quite a bit of time paying that down. After the war, expenses declined dramatically in the absence of the high cost of waging the war. As a result, the debt also came down. According to the president’s budget for fiscal year 2010, the national debt will pass 100 percent of GDP in 2011, something that hasn’t happened since the end of World War II.

Today, politicians and pundits rail about the massive deficits and the need to increase revenue and cut spending. Increasing revenue means raising taxes, something no politician wants to be accused of. Lowering expenses is an equally formidable challenge. Where do you cut?

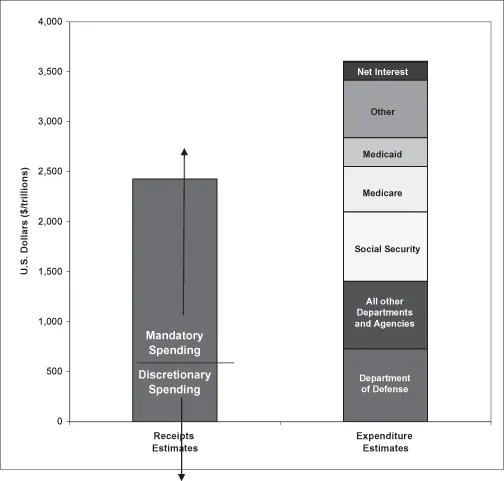

Figure 1.2 shows where the money went in 2010. The shaded area to the right shows that over 50 percent of our budget expenditures are “mandatory” for things like Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and the interest on the national debt. These simply can’t be cut. Of course, we can tinker with Social Security—by raising the age limit for retirees for example—but most politicians still treat Social Security as the third rail of politics: Touch it and you die.

The largest budget expenditure among the so-called discretionary spending categories is defense. Few politicians are eager to justify major cuts in defense spending, particularly in the aftermath of 9/11. That leaves very little room for making significant cuts.

So what about raising taxes? Here the debate gets heated. There is the constant reminder by Dr. Arthur Laffer (with whom one of us [Tanous] coauthored a book) that within certain limits raising taxes actually decreases tax revenue and lowering taxes increases tax revenue. The idea is that taxes are about incentives, so if you raise taxes, there is less incentive to take risk and if you lower taxes there is more incentive to work hard and take risk; hence more people working and building businesses results in higher tax receipts even if they are at a lower rate.2 But no matter which side of that argument you take, we all agree that raising taxes is hard to do, especially for politicians who have to agree to vote on it. If anything, this explains why it is so difficult to get out of the deficit morass. That is, until the deficit becomes a crisis and forces drastic action.

That is, of course, precisely what we see in our immediate future.

The Ticking Time Bomb

Sovereign debt issues in 2010 are estimated to total $4.5 trillion.3 This sum is triple the amount of average debt issuance by developed countries over the preceding five years. U.S. total debt (including debt held by government agencies) has risen 50 percent since 2006 to over $14 trillion. These numbing numbers start to lose meaning after a while, at least until we put them in some other context.

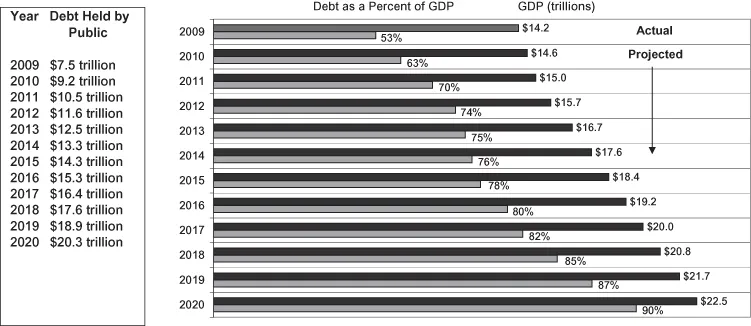

To that end, let’s have a look at the trend of U.S. debt in Figure 1.3. Keep in mind the source of this data, the Congressional Budget Office, which is nonpartisan. Although that doesn’t guarantee that its estimates will be right, it does ensure that the projections will not be tainted by political bias.

Clearly, the trend is scary. According to these projections, which may well prove too conservative, U.S. debt (external) as a percentage of GDP will attain 90 percent in 2020. We believe that benchmark will come even sooner. And what happens when a country’s debt reaches the level of 90 percent of GDP? (To avoid confusion, let us reiterate that there are two ways that federal debt is reported. One includes the internal debt such as borrowings by the government from the Social Security fund, which is essentially internal bookkeeping. The second method involves only the U.S. external debt held by the public and foreign governments.)

Economist Carmen Reinhart, who with Kenneth Rogoff coauthored the highly praised book This Time It’s Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly (Princeton University Press, 2009), made the point of how heavily debt weighs on GDP. In an interview with Forbes magazine, Reinhart discussed her finding that a 90 percent ratio of government debt to GDP is a tipping point in economic growth. When government debt crosses that 90 percent line, the economy of the country in question has a growth rate that is 2 percent lower than an economy that has less debt.4

This is a significant point. As the United States approaches a debt level of 90 percent of GDP, if history holds and we subsequently have a 2 percent lower rate of growth, our growth will not be strong enough to sustain full employment and service our debt. This will further exacerbate and accelerate the debt crisis.

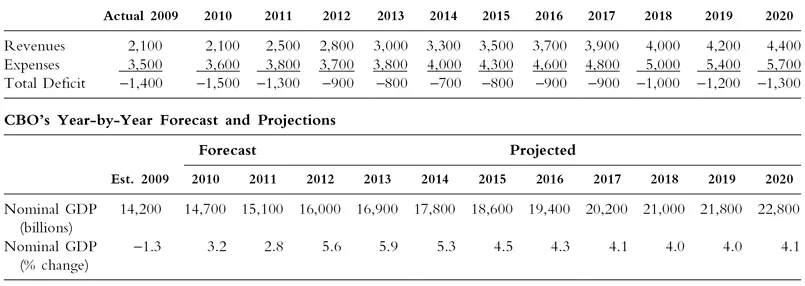

Table 1.1 shows the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimate of the projected total deficits through 2020. Its estimates are arguably optimistic. As bad as these estimates look, the reality is that they will prove overly optimistic. Here’s why: According to the CBO, “federal debt held by the public will stand at 62 percent of GDP at the end of fiscal year 2010, having risen from 36 percent at the end of fiscal year 2007, just before the recession began. In only one other period in U.S. history—during and shortly after World War II—has that figure exceeded 50 percent.”5

Table 1.1 CBO’s Estimate of the President’s Budget (billions)

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Looking at the bottom line of Table 1.1 (Nominal GDP, % change), the CBO rates of growth of GDP seem very optimistic to us and many others. The projected growth rates of GDP in 2012, 2013, and 2014 are all in excess of 5 percent, ranging from 5.3 percent to 5.9 percent. We don’t think this is realistic. Most CBO original projections turn out to be wrong, but then again, almost all long-term economic predictions are wrong.

Remember that consumer spending accounts for nearly 70 percent of GDP. With unemployment stuck above 9 percent and consumer confidence relatively low, how likely is it that GDP is going to grow at very high rates? And if the growth isn’t there, revenues will be lower than expected and the deficit will increase even faster. An aging population and much higher health care costs will push federal spending as a percentage of GDP much higher. What then?

The Rising Debt and the Rising Cost of Debt

In May 2010, Moody’s—one of the major credit rating agencies—estimated that the cost of servicing the U.S. national debt could rise to as much as 23 percent of federal revenues by 2013, assuming much less optimistic assumptions about economic recovery than those published by the CBO.6 When the debt servicing costs for a nation reaches 18 percent or more, that country is on the equivalent of a “credit watch” by the rating agencies. Indeed, none of the major credit agencies wants to see sovereign debt service in excess of 20 percent. If that happens, the credit agencies will downgrade that country’s debt.

Might the United States seriously be in danger of a credit downgrade? Well, yes. Interest rates today are at or near all-time lows, so the cost of servicing the debt is also low. And, of course, the debt is rising perilously and, as we have seen, we risk an explosion of new debt as a result of the growing deficits. If interest rates rise, which we believe is certain to happen and which will be discussed in a later chapter, then we have the double negative effect of higher interest costs and higher debt adding to our overall costs of servicing the debt.

A downgrade of U.S. debt has never happened, but if it does, there is no doubt that such an event would send shock waves through the world of finance. No one can reasonably predict the outcome if a downgrade occurs, but it is sure to be ugly. (Think of plummeting prices of U.S. Treasury bonds and notes!)

Will the United States Default on Its Debt?

In a word, no. The United States doesn’t ever need to default so long as our currency remains desirable and relatively safe. We always have the option of the printing press to make more currency with which to pay back the debt. As inflation lurks, we will wind up paying back our old debt with cheapened dollars. This scenario is widely discussed as a possible solution to our towering debt.

But is it realistic?

Here’s the problem. About 40 percent of our federal debt is scheduled to mature by midyear 2011. Seventy percent of the debt will mature within five years.7 If investors smell even a whiff of inflation, they will demand higher interest rates when the government attempts to roll over (reissue) the debt as it m...