This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

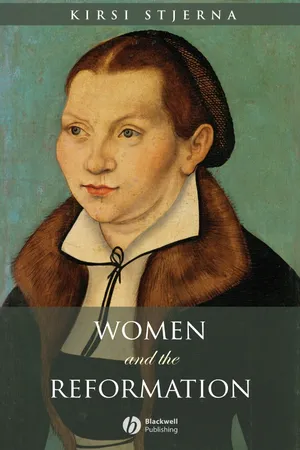

Women and the Reformation

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Women and the Reformation gathers historical materials and personal accounts to provide a comprehensive and accessible look at the status and contributions of women as leaders in the 16th century Protestant world.

- Explores the new and expanded role as core participants in Christian life that women experienced during the Reformation

- Examines diverse individual stories from women of the times, ranging from biographical sketches of the ex-nun Katharina von Bora Luther and Queen Jeanne d'Albret, to the prophetess Ursula Jost and the learned Olimpia Fulvia Morata

- Brings together social history and theology to provide a groundbreaking volume on the theological effects that these women had on Christian life and spirituality

- Accompanied by a website at www.blackwellpublishing.com/stjerna offering student's access to the writings by the women featured in the book

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Women and the Reformation by Kirsi Stjerna in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & History of Christianity. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

Options and Visions for Women

CHAPTER 1

Prophets, Visionaries, and Martyrs Ursula Jost and her Publisher Margarethe Prüss

Introduction – Medieval Women Visionaries

Did the Reformation offer women new possibilities of embracing religious leadership roles and using their theological voice in public, or did it limit women’s options? What happened to the women mystics and visionaries of the medieval world? How well did the Protestants’ teaching of the priesthood of all believers apply to women? Did Protestant theology and reforms promote spiritual equality and emancipation for all concerned, including the women? The answers are ambiguous.

On the one hand, a seed of radical emancipation was embedded in the reformers’ teaching of justification by faith as a gift from God for humans without a merit of their own. The priesthood of all believers would thus seem like a natural expression of – and a foundation for – spiritual equality. The eagerness with which many a woman joined the Protestant believers tells that they heard in the new preaching a promise worth responding to, without perhaps fully comprehending at first what that promise entailed for them as women in particular. On the other hand, there was no collective voice of women and thus no joint recorded “women’s opinion” on this, just documents on individual responses. The number of sources from (and on) the Reformation women pale in comparison to those preserved from their medieval foremothers. The apparent disappearance of women writers coincides with the Protestants’ dismissal of the mystics, prophets, and saints who in the medieval religious scene had often been important female counterparts to the otherwise exclusively male clergy and school theologians and androcentric religious imagery.

The late medieval context and women’s religious roles there offer a revealing mirror to examine how women’s situations changed both for better and for worse. These changes can be understood in light of the basically unchanged gender conceptions, societal factors, and new theological emphases. The most important changes in women’s lot arise from the new perspectives on spirituality and vocation.

In spite of the tenaciously preserved Pauline teaching about women’s silence and submissive roles in the Church, and the institutionally executed rules against women’s teaching, preaching, and public roles, there have been individual women in Christian history who have found ways to break the gender rules. Against the regulations limiting women’s theological activity and voice, those motivated to do so have succeeded in establishing themselves as teachers and leaders. They have done so as lay persons and as private believers, more often than not “authorized” by specific spiritual convictions and experiences they have purposefully traced back to God’s irresistible calling. The Middle Ages especially produced an astonishing number of female visionaries with “divine messages.” Because of the public character of their actions and identities, these women stand out as exceptional, and as disobedient to the centuries-old ideals set for Christian women. Transgressors whose actions could be deemed to originate from God’s divine action could win forgiveness and even respect, whereas the same latitude was not afforded the women who broke the rules “on their own,” without any claimed or manifest supernatural authorization.

Since the earliest days of Christian history, individual women who have espoused the roles of religious leaders and teachers have typically drawn their justification for such “unwomanly” activity from their transforming religious experiences of mystical nature. In the pre-Reformation context in particular such spiritual experiences were far from uncommon. Quite to the contrary, mysticism flourished in medieval Christianity, as an important counterpart to the official, institutionalized religion dominated by the clergy. It is hardly a coincidence that many of the mystics were members of laity and women for whom mysticism offered the only possible platform for teaching and preaching and religious authority.

“In the first part of the sixteenth-century, as in the late Middle Ages, women were sometimes seen as spiritual authorities because of their visionary and prophetic experiences. They based their claim to authority not on office, but on experience, an extraordinary vocation. Such experience often took the form of prophetic visions” (Snyder 1999, 282). Scholarship has established that the

visions were a socially sanctioned activity that freed a woman from conventional female roles by identifying her as a genuine religious figure. They brought her to the attention of others, giving her a public language she could use to teach and learn. Her visions gave her the strength to grow internally and to change the world, to preach, and to attack injustice and greed, even within the church. Through visions, she could be an exemplar to other women, and out of her own experience, she could lead them to fuller self-development. (Ibid. See also Snyder and Hecht 1996.)

Only few women would write in their own name (for instance, Marguerite Porete, burned at the stake with her book in the early fourteenth century, and Christine de Pizan, earning her living as a professional writer from the fourteenth to the fifteenth century). A preferred option was for a woman to identify herself – with the desired affirmation of others – as a messenger and a mouthpiece of God. A “documented” supernatural call would supersede human orders. In a parallel order created by God’s spirit, women could see visions, prophesy, teach, and publish.

The tradition of mystical and prophetic writing flourished in the Middle Ages. For instance, Hildegard von Bingen and the visionaries from the Helfta Convent (from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries) and Julian of Norwich, Caterina da Siena, and Birgitta of Sweden (from the fourteenth to the fifteenth centuries) earned a following as holy women who had dedicated their lives to a God-given mission (as they perceived it) to deliver divine messages. They attracted a following among the people as well as suspicion from the ecclesial authorities. In their survival and success the advocacy of male authorities, often confessors and scribes, was instrumental, especially in proving the visionaries’ orthodoxy and promoting official recognition of their sanctity. Further proofs of the visionary women’s exceptional authority as spiritual leaders came from their extraordinary lives and manifestation of “manly” virtues. In many ways the holy women needed to give up their womanhood and self-identity and annihilate their human needs and relations in order to excel in ascetic and contemplative practices, in the process of becoming non-gendered instruments of God whose jealous love was allconsuming. For the women themselves, it appears, this process could mean spiritual emancipation, within the framework of what was esteemed and considered possible for women in terms of religious roles and experiences.

In the high and late Middle Ages, in the climate of a heightened interest in mysticism, there was an upsurge in the number of lay teachers concerned with the spiritual wellbeing of people and critical of the rise of clerical power and accumulation of problems in the Church. Numbers of lay visionaries, prophets, and mystics offered their visions for reform, often envisioning spiritual and moral reforms for which they would be the starting point; this kind of transformation would later characterize the heart of the Catholic reform in the sixteenth century. Monasteries and convents, which had multiplied by the late Middle Ages, provided a natural environment and stimulus for mystics and visionaries, many of whom became forerunners for the Reformation, both Protestant and Catholic. In the latter, the mystics continued to function in influential roles as spiritual leaders; in the former, the mystics all but disappeared, and with them women prophets and visionaries.

This speaks of shifting priorities in spiritual life, piety, and theology: spiritual experiences and individual bodily and charismatic expressions of religiosity became devalued while the “extra nos” effectiveness of grace in individuals’ lives became emphasized. For everyone, male or female, who took part in the Protestant Reformation both the notion and expressions of spirituality underwent a fundamental change. Excluded from the pulpit and public teaching places, women also lost their role as female prophets and mystics in the Protestant church, where their spiritual life was more or less confined to the domestic world. From now on, women would need to find other callings to make their mark in the “new” church.

To sum up: For sixteenth-century Protestants, the pure proclamation of the Word was seen as key to reform. New emphasis was placed on preaching the Word purely, and living it out in one’s vocation; the first aspect was open only to men, the second to women as well. Protestant women gained home and “world” as their new holy land, while they became seemingly (to us anyway) imprisoned in this exclusively preached domestic model for women. With the coinciding loss of the convents, women lost the environment that had most essentially supported women’s individual spiritual development and mystical activity and nurtured many a visionary writer. Protestant women were to forget prophesying and mystical experiences and instead embrace their domestic holy vocations as spouses, mothers and caretakers of their households. While some women cherished this interpretation of the gospel, others rejected it. Some endeavored to combine both. In the early years of the Reformation, a minority of women managed to continue in the roles of the prophets while also embracing their marital and maternal duties. The story of these “radical” Protestant women intertwines with another tragic story: that of the martyrs – women and men believing and acting against the prevalent norms. As a tribute to those women who died for their faith, many of whom remain nameless, the discussion here begins with those who were most persecuted.

Anabaptists and Martyrs

The Anabaptist prophets experienced a burst of freedom in the early years of the movement, before being confined similarly to their sisters in the mainstream Protestant traditions. They welcomed the Protestant teaching of the goodness of marriage, and some of them also shared the pulpit, so to speak, with their husbands, in the roles of a prophet.

The activity of the spiritually authorized lay teachers continued among the radical reformers. The term “radical” refers to those Protestant groups (formed from approximately the 1520s onwards), of which the Anabaptists were one, that emphasized the independent activity of Holy Spirit in the interpretation of the Scripture and practiced believer’s baptism (that is to say, adult baptism as a testimony of one’s faith). With the principle of sola scriptura, they rejected earthly authority, refused civil and military service and the giving of oaths, in conformity with their apocalyptic teachings. Diverse groups which coalesced around these basic tenets (the Swiss, the South Germans and Austrians, and the North Germans and Dutch) sought separation from the “world” and were persecuted throughout Europe. The 1685 Martyrs Mirror reported that 30 percent of all martyrs were women.

While there were many reasons for the persecutions of the Anabaptists, the issue of spiritual experiences and the work of the Holy Spirit was of central importance in regards to women. Namely it was the spiritual experiences that carved for Anabaptist women a unique place in Protestant history, and which also caused them great peril.

The identification of this radical “spiritual” emphasis is crucial to the telling of the story of Anabaptist women. Appealing to the Holy Spirit as the central interpretive agent meant that a spirit-filled, illiterate, or semi-literate woman or man would be a truer exegete of Scripture than would a learned professor lacking the Spirit. This spiritual and egalitarian approach to scripture, which emerged in Luther and Zwingli’s own movements, opened the door to the participation of women and uneducated commoners in radical and Anabaptist reform. (Snyder and Hecht 1996, 3)

The magisterial Reformers disapproved: their opposition to the radicals was even fiercer than their prohibitions against women’s teaching.

Mainstream reformers preached the good news of justification by faith alone with a renewed emphasis on the work of the Word and the two recognized sacraments. Stressing the importance of the responsibilities of all believers, on the one hand, they also upheld the institutional means of grace and the “right call” to the office of the Word, on the other. Thus, even with the agreed upon principle of sola scriptura and the exhortation for the laity to read their Bibles, now increasingly available in the vernacular, the reformers remained suspicious of Spirit-filled individuals sharing their spiritual experiences beyond the ordered church structure and its authorized offices. At the heart of the disagreement was the understanding of the work of the Holy Spirit and of what constituted “spiritual.” In the case of women, the dangers were only magnified. Anabaptist women engaged in prophetic activity were doubly disruptive of the order in the new church(es) that had no more tolerance for heresy, disobedience, or disruption of order than the Catholic church had in the outset of the Protestant movements. Anabaptists who did not adhere to the accepted forms of faith, whether Catholic or Protestant (primarily the Lutherans and their Augsburg Confession), and who practiced adult (re)baptism in defiance of the imperial law, were in the position of outlaws and were persecuted throughout the Europe.

Mainstream and radical reformers found agreement in one issue in particular: God would want women to remain subject to men, staying in the home as spouses and mothers. Throughout the early years of the movement, Anabaptist women, however, could espouse exceptional opportunities for religious leadership, especially as prophets. As the movement became institutionalized, though, many of the women’s early opportunities for visible leadership roles were lost (just as they had been in the early “heretical” movements, such as the Montanists). That scholars disagree on the degree of women’s emancipation among the radicals reflects the ambiguous nature of women’s history in general and speaks of the complex reality of the gendered norms that affected every movement. In general, it seems, only the work of the Spirit could disrupt the order that regulated gender relations in church and society!

The degree of women’s freedom in Anabaptist circles varied from place to place, and from teacher to teacher (for instance, Melchior Hoffman saw the office of a prophet suitable for women, whereas Menno Simons interpreted the Scripture endorsing women’s submission), and, generally speaking, the Anabaptists sent an ambivalent message to women: On the one hand, their break with the church institution and their enforcement of subjectivity in religious matters in the early days suggested the liberating effect of the Spirit in individuals’ lives and ensuing religious autonomy beyond institutional control. The theology of the egalitarian pouring out of the Spirit and trust in charismatic experiences allowed both lay men and women to assume the role of a prophet, one with religious authority and a public voice. “The ‘calling of the Spirit’ which provided the foundation for the Anabaptist movement was radically egalitarian and personal, even though it led individuals into a commitment to a community” (Snyder and Hecht 1996, 8). Eventually, however, Anabaptist women would be subjected to the same gender conventions as others, with an expectation to find fulfillment in a patriarchally ordered marriage and household and church.

While at no time was there full equality, in the beginning of the movement several factors allowed Anabaptist women more opportunities to participate in the life of the church than they could in society at large. Throughout their history, women contributed instrumentally in the Anabaptist communities of faith. They even “appointed themselves to places of leadership. No one asked them. They sometimes became apostles, prophetesses, and visionaries. Their messages were unpredictable” (Sprunger 1985, 53). The activities of Elisabeth of Leeuwarden following what she claimed was just such a call by the Spirit of God made her famous. Before being martyred in 1549, she was a known leader and an associate of Menno Simons in the northern Dutch Anabaptist circles. A learned, independent woman praised for her “manly courage” (Joldersma and Grijp 2001), Elisabeth had come from a convent background and bravely assisted in the Anabaptist network, establishing herself as the first known Mennonite deaconess. Other women, like Elisabeth, performed informal proselytism, crafted hymns, hosted Bible readings and sewing circles, and worked actively at a grass-roots level. Some distributed alms and housed itinerant ministers and refugees. They spread the gospel by word of mouth. In all these activities Anabaptist women gave an extraordinary lay witness. For instance, Aeffgen Lystyncx in Amsterdam, a wealthy lay woman, organized conventicles. At Schleiden, two women notably acted as itinerant preachers: Bernhartz Maria of Niederrollesbroich, with ecstatic visions and Maria of Monjou, executed by drowning 1552. A few Swiss Anabaptist women earned fame as prophetesses: Margaritia Hattinger of Zurich and Magdalena Muller, Barbara Murglen, and Frena Bumenin of St Gall. (See Sprunger 1985, 52–7; Snyder and Hecht 1996, 8, 10–11, 14–15, 97–8; Wiesner 1989, 15–17.)

A particularly tragic chapter of Anabaptist history was lived in Münster, where women found themselves in an abusive situation under the totalitarian rule of Jan Mathjis and Jan van Leiden, who promoted polygamy and women’s total subjection to their husbands, with a threat of death or imprisonment. The lives and deaths of the martyrs were documented in The Martyrs Mirror (by Thieleman Jansz van Braght [1625–64]), also called The Bloody Theater or Martyrs Mirror of the Defenseless Christians. It includes information on 278 women, who constituted one third of all the martyrs, who were drowned, burned, strangled, and buried alive for their faith, with or without their husbands (for instance, Anneken Jans and Weynken Claes.) Their gender made the persecuted women exceptionally vulnerable.

Each individual woman was put in a position of defending herself against a weight of sanctioned authority and theological learning to which she, by virtue of being a woman, was allowed no access. Still, each Anabaptist woman was empowered by the Anabaptist principles of encouraging every believer, female as well as male, to independently search Scriptures and to share their understanding of the truth with others. (Joldersma and Grijp 2001, 27–36 at 27–8)

Women’s answers demonstrated their learning and bravery as well as conviction of faith.

Martyrdom was not limited to the Anabaptists. In addition to widespread witch hunts, stories of female martyrs came from all over Europe. Especially bloody periods marked by the French Wars of Religion and the religious strife in England throughout the Tudor and Stuart period produced martyrs on both sides as the religious adherences and policies of the heads of state underwent successive changes. (See Bainton 2001b, 211-29, 159–209) From England, the telling records of trials against Lutheran, Calvinist, or Anabaptist women portray brave women with convictions they were willing to die for. As an example, English gentlewoman Anne Askew was executed in 1546 after being tortured and scrutinized for her reforming views and activities – and in an attempt to secure evidence of heresy against the queen, Katherine Parr, last of Henry VIII’s wives, whose own reformist sympathies were unpopular with the powerful bishop of Winchester, Stephen Gardiner. Anne left a detailed recording of her ordeal in her own writing (the first of which dates from 1545), which provides an autobiographical picture, with a description of her gruesome torture, as well a woman’s interpretation of several debated theological issues, such as Christ’s presence in the Lord’s Supper (see Beilin 1996). As another example, the most famous female Protestant martyr in England was the beheaded second wife of Henry VIII: Anne Boleyn’s story exemplified tragically the hazards a sixteenth-century woman, even a queen, faced due to her religious choices, gender, and sexuality (see Warnicke 1989). (Her daughter, Elizabeth I, had her own reasons to remain in public as asexual and neutral in religious matters as possible.) Many of the Reformation women in positions of power sought to intervene with the persecutions and save believers from execution. For instance, Marguerite de Navarre and her daughter Jeanne d’Albret, and their friend Renée de France, were famous for their asylums and protection of the Protestants. With a shared attitude against violence, Katharina Schütz Zell and Argula von Grumbach wrote on behalf of religious tolerance and acted in defense of those accused for their beliefs. While women died for their faith just as men did, many women leaders (with the notable exception of Mary Tudor and Catherine de Médicis) seemed more interested in ending the violence practiced in the name of religion than killing for it.

The perspectives provided by the Anabaptist women and the martyrs demonstrate the ambiguity of the Reformation’s promise to women. They reveal, once again, the intertwining of politics and religion, with gender factoring in both. Last but not least, their stories provide evidence for the determination, tenacity, and shrewdness with which women took the roles of leadership, witnessing and confessing, even at times when much less was expected of them.

Prophets in Strasbourg and their Publisher Margarethe Prüss

The tolerant free city of Strasbourg, home of Katharina Schütz Zell, was a central place for prophetic activity and for the publication of many radical and lay works (especially between 1522 and 1534). Many of the city’s women were married to Anabaptists or Spiritualists (men and women together accounting for 10 percent of the population). Some of them became known as prophets and were associated with a visiting Anabaptist Melchior Hoffman (1529), who assisted in the publication of the prophetic works he respected. Among the most influential of the illiterate female prophets were Ursula Jost and Barbara Rebstock, the wife of a weaver, who served as an “elder of Israel” in her Anabaptist congregation. Both were close associates of Hoffman and were influenced by Hans Hut. Their visions, filled with zeal and biblical references, were published by Melchior Hoffman and a brave female publisher Margarethe Prüss, one of the most daring and productive publishers in Strasbourg. The daughter of a printer, wife of two printers, and a printer on her own, she was neither a prophet nor a teacher herself, but became instrumental in publishing the prophets’ works. Her third marriage to an Anabaptist may, like her decision to publish “forbidden” or potentially scandalous works, reveals her religious sympathies, given the persecuted status of the Anabaptists. (See Chrisman 1972, 159–160 on her role as a publisher in the reformation in Strasbourg.)

In 1510 her father, Johann Prüss, died and she inherited his print shop, which had been in operation since 1504. She then married (1511–22) Reinhard Beck, who became co-owner of the “Prüss-Beck” print shop. Whereas her father had printed Catholic works, Marguerite and Reinhard chose to print reformation materials, such as Martin Luther’s and Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt’s works, along with classical and humanist works in both Latin and German. Limits set by the town guild limited the period for which a woman could operate a business alone, and so, after Reinhard’s death, Marguerite’s business activities were threatened. She managed to establish another print shop, which she operated alone until she hired Wolfgang Foter, who would become her sonin-law, and then in 1524 she married Johann Schwann of Marburg (an ex-Franciscan), with whom she continued to publish reformation materials until his death in 1526. In May 1527 she married for the third time, this time to a known Anabaptist, Balthasar Beck.

In the 1530s, risking (and in the Balthasar’s case suffering) arrest and financial hazards, the Prüss-Beck press published the works of Anabaptists and Spiritualists, including those of Ursula Jost, Sebastian Franck, and Melchior Hoffman, among others considered radical either because of their content or their author. (For instance, they published Katharina Schütz Zell’s hymnbook based on Michael Weisse’s songbook from Bohemia.)

Margare the clearly was aware of the ideological bent of the books being produced by her press. In fact, it appears that Margarethe’s choice of husband/printers was coloured by her commitment to the continued printing of radical materials. This woman pragm...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- PART 1

- PART 2

- Conclusions and Observations on Gender and the Reformation

- Bibliography

- Index