![]()

Chapter 1

The “What” and the “How” of Student-Centered Leadership

Most school leaders are motivated by the desire to make a difference to their students. They want to lift their students’ achievement, increase their confidence, and give them opportunities they would never find elsewhere. Although we should admire their moral purpose, fine words and high ideals are not enough. If leaders don’t know how to put their words into action, if they follow the wrong paths and take the wrong turns, then their sense of moral purpose can quickly give way to cynicism, frustration, and fading commitment.

This book is not another call to the moral high ground. Most educational leaders are already there or at least want to be. Instead, it is a book about how to turn ideals into action. It provides leaders with guidance about how to make a bigger difference to their students—guidance that is based not on fad or fashion but on the best available evidence about what works for students.

When school leaders reflect on what keeps them in a highly challenging job, they typically describe the difference they make to the lives of children and the difference children make to their own lives. They describe how, on the “horrible days,” they get an emotional lift by stopping by classrooms to see children and celebrate their achievements. They believe passionately that “you can’t beat working with children.” But they are just as aware of the children they have not reached—the children for whom school was a place of failure and humiliation or the children for whom school did make a difference but not enough to overcome the challenges of their family circumstances.

The job of school leadership offers enormous rewards and increasing challenges. My motivation for writing this book is to help school leaders increase the rewards while meeting the challenges by describing, explaining, and illustrating new research evidence about the types of leadership practice that make the biggest difference to the learning and well-being of the students for whom they are responsible.

Leadership in Challenging Times

The expectations for today’s school leaders have never been more ambitious. Leaders work in systems that expect schools to enable all students to succeed with intellectually challenging curricula. Although no education system in the western world has achieved this goal, and it is not clear how it can be achieved at scale, school leaders are held responsible for making progress toward it. In the United States, under the federal legislation known as No Child Left Behind (NCLB), the accountabilities associated with these policy expectations can be punitive and demoralizing, especially for leaders in schools that serve economically disadvantaged communities (Mintrop & Sunderman, 2009).

These ambitious expectations come at a time when the school population has never been more diverse. This diversity has revealed the limitations of schooling systems that cannot rapidly teach children the cognitive and linguistic skills that enable them to engage successfully with the school curriculum. Because increasing numbers of children arrive at school without these skills, achieving the goal of success for all students may require major changes to business as usual.

On the positive side, these increased expectations have been accompanied by a greater understanding of the importance of leadership for achieving the goal of success for all students. A new wave of research on educational leadership has shown that the quality of leadership can make a substantial difference to the achievement of students, and not just on low-level standardized tests (Robinson, Lloyd, & Rowe, 2008). In schools where students achieve well above expected levels, the leadership looks quite different from the leadership in otherwise similar lower-performing schools. In the higher-performing schools it is much more focused on the business of improving learning and teaching.

There is no doubt that this body of evidence about the links between leadership and student outcomes has been noticed by policy makers and professional associations. It has informed the development of educational leadership standards in the United States (Council of Chief State School Officers, 2008), the work of the National College of School Leadership and Children’s Services in England (Leithwood, Day, Sammons, Harris, & Hopkins, 2006), and the development of leadership frameworks in Australia and New Zealand (New Zealand Ministry of Education, 2008). The research has confirmed what school leaders knew all along—that the quality of leadership matters and that it is worth investing in that quality.

Another positive feature of the leadership environment is the shift from an emphasis on leadership style to leadership practices. Leadership styles, such as transformational, transactional, democratic, or authentic leadership, are abstract concepts that tell us little about the behaviors involved and how to learn them. The current emphasis on leadership practices moves leadership away from the categorization of leaders as being of a particular type to a more flexible and inclusive focus on identifying the effects of broad sets of leadership practices. Rather than anxiously wonder about whether you are, for example, a transformational leader, I will be encouraging you to think instead about the frequency and quality in your school of the leadership practices that this new research has shown make a difference to the learning and achievement of students.

What Is Student-Centered Leadership?

In this book, the ruler for judging the effectiveness of educational leadership is its impact on the learning and achievement of students for whom the leader is responsible. Although educators contest the value to be given to particular types of achievement, and argue about whether certain assessments and tests measure what is important, the principle at stake here is willingness to judge educational leadership by its impact on the educational outcomes of students. Do the decisions and actions of the school’s leadership improve teaching in ways that are reflected in better student learning, or is their focus so far removed from the classroom that leadership adds little value to student learning?

There are compelling ethical arguments for student-centered leadership. Because the point and purpose of compulsory schooling is to ensure that students learn what society has deemed important, a central duty of school leadership is to create the conditions that make that possible. Although this criterion for leadership effectiveness might seem to some readers to be too narrow, in reality it is not because leaders need to work on so many different fronts to achieve it.

Typically, judgments of leadership effectiveness stop short of asking about effect on student learning. Perhaps the most common approach to judging school leadership is the quality of school management—children are happy and well behaved, the school is orderly, the property is looked after, and the finances are under control. Although high-quality school management represents a considerable achievement, it should not be equated with leadership effectiveness because it is possible for students in well-managed schools to be performing well below their expected level. High-quality management is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for leadership effectiveness because it requires, in addition, that the school’s management procedures ensure high-quality teaching and learning. There is a considerable stretch between the two.

A second approach to judging leadership effectiveness is based on the quality of leaders’ relationships with the adults in the system. Principals who are popular with staff and parents and get along with district officials are judged to be effective. These relationships are important because little can be achieved by school leaders if they alienate their staff, are in constant dispute with district officials, or cannot earn the trust of their communities. But once again, this criterion is not sufficient for judging the effectiveness of school leaders because good relationships with adults do not guarantee a high-quality learning environment for students.

A third unsatisfactory approach to judging leadership effectiveness is to equate it with innovation. Leaders who get on board with the latest innovations in school organization, curriculum, or community outreach often have high profiles and are showcased as effective leaders. But like good staff relationships, innovative practice is not necessarily predictive of student learning. We know that many innovations do not work and that schools engaged in multiple innovations can burn out staff, create incoherence in the instructional program, and actually make things worse for their students (Hess, 1999).

One of the reasons that school management, staff relationships, and innovative practice have overshadowed student impact as the criterion for leadership effectiveness is that it is very difficult to isolate the contribution of leadership to student progress. Except in the smallest of our schools, leaders influence students indirectly by creating the conditions required for teaching and learning. It is easier to create those conditions in schools that enroll students with high levels of prior achievement than it is to create those conditions in schools that enroll students with lower achievement levels. The apparent success of leaders in the first type of school may be more a reflection of the students and of the community from which they are drawn than of the effectiveness of the leadership.

The indirectness of leadership effects on students, plus the confounding influence of factors such as student and community background, make it very difficult to isolate out the contribution of leadership itself. That is probably why leadership effectiveness has been judged by qualities such as staff relationships and degree of innovation—qualities that are assumed to be good for students. In the absence of good evidence, these taken-for-granted assumptions have become substitutes for student-centered measures of leadership effectiveness. In advocating a student-centered approach to leadership effectiveness, I am seeking to disrupt the assumption that what is good for the adults is good for the students and to encourage a more deliberate examination of the relationship between the two.

Whose Leadership?

My answer to this question is that this book is for everyone who exercises leadership in schools. But that answer just raises further questions about what I mean by leadership. And until we sort out what is meant by leadership in this book, I can’t answer the question of whom this book is for.

It is commonly asserted that leadership is the exercise of influence, but so is force, coercion, and manipulation, and we wouldn’t call those types of influence leadership. So there must be something else. Leadership is distinguished from force, coercion, and manipulation by the source of the influence. The influence that we associate with leadership comes from three different sources. The first source is the reasonable exercise of formal authority—the critical factor here is that those who are influenced see the use of the authority as reasonable. The principal had a tough decision to make—she explained why she made it, and although we didn’t all agree we do understand that a decision had to be made.

A second source of leadership influence is attraction to one or more of the personal qualities of the leader. The leader is admired for his dedication, selflessness, ethic of caring, or courage. This is when character enters the frame—attractive personal qualities increase the chance of being influential with colleagues. A third source of leadership influence is relevant expertise—one gains influence by offering knowledge and skills that help others make progress on the tasks for which they are responsible.

In the following scenario in which a group of teachers meet to review the results of a recent assessment in science, we see the fluid operation of these sources of influence (Robinson, 2001, p. 92):

Mary, the head of science, is chairing a meeting in which her staff are reviewing the results of the assessment of the last unit of work. She circulated the results in advance, with notes about how to interpret them, and asked the team to think about their implications for next year’s teaching of the unit. The team identifies common misunderstandings and agrees they need to develop resources that help students to overcome them. Julian, a second-year teacher, was pretty unhappy with the assessment protocol used this year and suggests revisions that he thinks will give more recognition to students who have made an extra effort. Most of his suggestions are adopted. Lee, who teaches information technology as well as science, shows the group how the results have been processed on the computer so that they can be combined with other assessments and used in reports to parents and the board. Several team members express nervousness about reporting to the board so they decide to review a draft report at the next meeting.

Mary, as head of science, influences her colleagues by asking them to prepare for their meeting and structuring the agenda. Despite Julian and Lee having no formal authority, they too influence how the task is done through their ideas about how to improve the assessment and reporting procedures. All three people in this meeting exercised leadership because their authority (in Mary’s case) and their ideas changed how the task was done. They moved fluidly between being in the lead and following the lead of others.

So leadership is, by its very nature, not just the purview of those with formal authority over others. One can also lead from a basis of expertise, ideas, and personality or character, and, in principle, these sources of influence are open to anyone. This means that leadership is by its very nature distributed. It follows, therefore, that this book is for all who seek to increase their leadership influence, whether or not they have a formal leadership position.

The “What” and the “How” of Student-Centered Leadership

If student-centered leadership is about making a bigger difference to student learning and well-being, then leaders need trustworthy advice about the types of leadership practice that are most likely to deliver those benefits. This book offers such advice based on a rigorous analysis of all the published evidence about the impact of particular types of leadership practice on a variety of student outcomes.

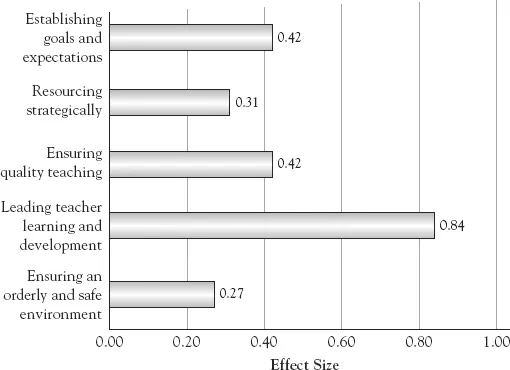

The first thing I learned in doing the analysis is that of the hundreds of thousands of studies about educational leadership only a minuscule proportion of them have examined the impact of leadership on any sort of student outcome. This, in itself, shows the radical disconnection between research on educational leadership and the core business of teaching and learning. In the end, I found about thirty studies, mostly conducted in the United States, that measured the direct or indirect impact of leadership on student outcomes. In about half of these thirty studies, leadership was measured by asking teachers to complete surveys about the practices of their principal. In the other half, teachers were asked about the leadership of their school. That is why the findings in Figure 1.1 tell us about the impact of school leadership rather than principalship. The student outcome measures were usually about academic achievement (math, literacy, or language arts), though a few studies used measures of social outcomes such as students’ participation and engagement in their schooling. The five dimensions presented in Figure 1.1 were derived by listing all the individual survey items that had been used to measure leadership and grouping them into common themes. Once the 199 survey items had been sorted into the final five leadership dimensions, the statistics reported in the original studies were used to calculate an average effect size for each dimension. The effect size statistic alongside each of the horizontal bars indicates the average impact of the leadership dimension on student outcomes. (More details about the methodology of the meta-analysis can be found in Robinson, Lloyd, & Rowe, 2008.)

Our analyses of these studies enabled us to sort the different leadership practices into five b...