This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Comic Relief: A Comprehensive Philosophy of Humor develops an inclusive theory that integrates psychological, aesthetic, and ethical issues relating to humor

- Offers an enlightening and accessible foray into the serious business of humor

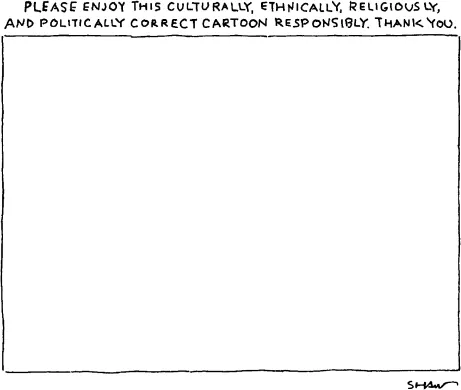

- Reveals how standard theories of humor fail to explain its true nature and actually support traditional prejudices against humor as being antisocial, irrational, and foolish

- Argues that humor's benefits overlap significantly with those of philosophy

- Includes a foreword by Robert Mankoff, Cartoon Editor of The New Yorker

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Comic Relief by John Morreall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

No Laughing Matter

The Traditional Rejection of Humor and Traditional Theories of Humor

Humor, Anarchy, and Aggression

Of all the things human beings do or experience, laughing may be the funniest–funny strange, that is, not funny ha-ha. Something happens or someone says a few words, and our eyebrows and cheeks go up, as the muscles around our eyes tighten. The corners of our mouths curl upward, baring our upper teeth. Our diaphragms move up and down in spasms, expelling air from our lungs and making staccato vocal sounds. If the laughter is intense, it takes over our whole bodies. We bend over and hold our stomachs. Our eyes tear. If we had been drinking something, it dribbles out our noses. We may wet our pants. Almost every part of our bodies is involved, but none with any apparent purpose. We are out of control in a way unmatched by any other state short of neurological disease. And–funniest of all–the whole experience is exquisitely pleasurable! As Woody Allen said of stand-up comedy, it’s the most fun you can have with your clothes on.

Not only is laughter biologically odd, but the activities that elicit it are anomalous. When we’re out for a laugh, we break social conventions right and left. We exaggerate wildly, express emotions we don’t feel, and insult people we care about. In practical jokes, we lie to friends and cause them inconvenience, even pain. During the ancient Roman winter festival of Saturnalia, masters waited on servants, sexual rules were openly violated, and religious rituals were lampooned. Medieval Europe saw similar anarchy during the Feast of Fools and the Feast of Asses, which were organized by minor clerics after Christmas. The bishop was deposed, and replaced with a boy. At St. Omer, they wore women’s clothes and recited the divine office mockingly, with howls. At the Franciscan church in Antibes, they held their prayer books upside-down, wore spectacles made from orange peels, and burned soles of old shoes, instead of incense, in the censers.1 Today, during Mardi Gras and Carnival, people dress in outlandish costumes and do things forbidden during the rest of the year, sometimes leading to violence.

In everyday humor between friends, too, there is considerable breaking of social conventions. Consider five of the conversational rules formulated by Paul Grice:

1. Do not say what you believe to be false.

2. Do not say that for which you lack adequate evidence.

3. Avoid obscurity of expression.

4. Avoid ambiguity.

5. Be brief.2

Rule 1 is broken to create humor when we exaggerate wildly, say the opposite of what we think, or “pull someone’s leg.” Its violation is a staple of comedians like George Carlin:

Legal Murder Once a Month

You can talk about capital punishment all you want, but I don’t think you can leave everything up to the government. Citizens should be willing to take personal responsibility. Every now and then you’ve got to do the right thing, and go out and kill someone on your own. I believe the killing of human beings is just one more function of government that needs to be privatized. I say this because I believe most people know at least one other person they wish were dead. One other person whose death would make their life a little easier … It’s a natural human instinct… . Don’t run from it.3

Grice’s second rule is violated for laughs when we present fantasies as if they were reasonable hypotheses. If there are rumors at work about two colleagues having an affair, we might say, “Remember on Monday when nobody could find either of them–I bet they were downstairs making hot monkey love in the boiler room.”

We can create humor by breaking Rule 3 when someone asks us an embarrassing question and we give an obviously vague or confusing answer. “You want to know why my report contradicts the Census Bureau? Well, we used a new database that is so secret I’m not at liberty to reveal its name.”

Violating Rule 4 is the mechanism of most jokes, as Victor Raskin showed in Semantic Mechanisms of Humor.4 A comment, a story, or a question-and-answer exchange starts off with an assumed interpretation for a phrase, but then at the punch line, switches to a second, usually opposite interpretation. A simple example is Mae West’s line, “Marriage is a great institution–but I’m not ready for an institution.”

Rule 5 is broken in comic harangues, such as those of Roseanne Barr and Lewis Black.

Not only does humor break rules of conversation, but it often expresses contempt or even hostility toward someone, appropriately called the “butt” of the joke. Starting in childhood, we learn to make fun of people by imitating their speech patterns, facial expressions, and gestures in ways that make them look awkward, stupid, pompous, etc. To be mocked and laughed at can be taken as seriously as a physical attack would be, as the 2006 worldwide controversy over the Danish cartoons about the Prophet Muhammad showed.

The Superiority Theory: Humor as Anti-social

With all the ways in which laughter and humor involve the loss of self-control and the breaking of social rules, it’s not surprising that most societies have been suspicious of them and have often rejected them. This rejection is clear in the two great sources of Western culture: Greek philosophy and the Bible.

The moral code of Protagoras had the warning, “Be not possessed by irrepressible mirth,” and Epictetus’s Enchiridion advises, “Let not your laughter be loud, frequent, or unrestrained.”5 Both these philosophers, their followers said, never laughed at all.

Plato, the most influential ancient critic of laughter, saw it as an emotion that overrides rational self-control. In the Republic, he said that the Guardians of the state should avoid laughter, “for ordinarily when one abandons himself to violent laughter, his condition provokes a violent reaction.”6 Plato was especially disturbed by the passages in the Iliad and the Odyssey where Mount Olympus was said to “ring with the laughter of the gods.” He protested that “if anyone represents men of worth as overpowered by laughter we must not accept it, much less if gods.”7

The contempt or hostility in humor, which Ronald de Sousa has dubbed its phthonic dimension,8also bothered Plato. Laughter feels good, he admitted, but the pleasure is mixed with malice towards those being laughed at.9

In the Bible, too, laughter is usually represented as an expression of hostility.10 Proverbs 26:18–19 warns that, “A man who deceives another and then says, ‘It was only a joke,’ is like a madman shooting at random his deadly darts and arrows.”

The only way God is described as laughing in the Bible is scornfully: “The kings of the earth stand ready, and the rulers conspire together against the Lord and his anointed king… . The Lord who sits enthroned in heaven laughs them to scorn; then he rebukes them in anger, he threatens them in his wrath.” (Psalms 2:2–5)

God’s prophet Elijah also laughs as a warm-up to aggression. After he ridicules the priests of Baal for their god’s powerlessness, he has them slain (1 Kings 18:27). In the Bible, ridicule is offensive enough to carry the death penalty, as when a group of children laugh at the prophet Elisha for being bald:

He went up from there to Bethel and, as he was on his way, some small boys came out of the city and jeered at him, saying, “Get along with you, bald head, get along.” He turned round and looked at them and he cursed then in the name of the lord; and two she-bears came out of a wood and mauled forty-two of them. (2 Kings 2:23)

Early Christian thinkers brought together these negative assessments of laughter from both Greek and biblical sources. Like Plato and the Stoics, they were bothered by the loss of self-control in laughter. According to Basil the Great, “raucous laughter and uncontrollable shaking of the body are not indications of a well-regulated soul, or of personal dignity, or self-mastery.”11 And, like Plato, they associated laughter with aggression. John Chrysostom warned that,

Laughter often gives birth to foul discourse, and foul discourse to actions still more foul. Often from words and laughter proceed railing and insult; and from railing and insult, blows and wounds; and from blows and wounds, slaughter and murder. If, then, you would take good counsel for yourself, avoid not merely foul words and foul deeds, or blows and wounds and murders, but unseasonable laughter itself.12

An ideal place to find Christian attacks on laughter is in the institution that most emphasized self-control and social harmony–the monastery. The oldest monastic rule–of Pachom of Egypt in the fourth century–forbade joking.13 The Rule of St. Benedict, the foundation of Western monastic codes, enjoined monks to “prefer moderation in speech and speak no foolish chatter, nothing just to provoke laughter; do not love immoderate or boisterous laughter.” In Benedict’s Ladder of Humility, Step Ten was a restraint against laughter, and Step Eleven a warning against joking.14 The monastery of Columban in Ireland assigned these punishments: “He who smiles in the service … six strokes; if he breaks out in the noise of laughter, a special fast unless it has happened pardonably.”15 One of the strongest condemnations of laughter came from the Syrian abbot Ephraem: “Laughter is the beginning of the destruction of the soul, o monk; when you notice something of that, know that you have arrived at the depth of the evil. Then do not cease to pray God, that he might rescue you from this death.”16

Apart from the monastic tradition, perhaps the Christian group which most emphasized self-control and social harmony was the Puritans, and so it is not surprising that they wrote tracts against laughter and comedy. One by William Prynne condemned comedy as incompatible with the sobriety of good Christians, who should not be “immoderately tickled with mere lascivious vanities, or … lash out in excessive cachinnations in the public view of dissolute graceless persons.”17 When the Puritans came to rule England under Cromwell, they outlawed comedy. Plato would have been pleased.

In the seventeenth century, too, Plato’s critique of laughter as expressing our delight in the shortcomings of other people was extended by Thomas Hobbes. For him, people are prone to this kind of delight because they are naturally individualistic and competitive. In the Leviathan, he says, “I put for a general inclination of all mankind, a perpetual and restless desire for Power after Power, that ceaseth only in Death.”18 The original state of the human race, before government, he said, would have been a “war of all against all.”19 In our competition with each other, we relish events that show ourselves to be winning, or others losing, and if our perception of our superiority comes over us quickly, we are likely to laugh.

Sudden glory, is the passion which makes those grimaces called laughter; and is caused either by some sudden act of their own, that pleases them; or by the apprehension of some deformed thing in another, by comparison whereof they suddenly applaud themselves. And it is incident most to them, that are conscious of the fewest abilities in themselves; who are forced to keep themselves in their own favor by observing the imperfections of other men. And therefore much laughter at the defects of others, is a sign of pusillanimity. For of great minds, one of the proper works is, to help and free others from scorn; and to compare themselves only with the most able.20

Before the Enlightenment, Plato and Hobbes’s idea that laughter is an expression of feelings of superiority was the only widely circulated understanding of laughter. Today it is called the “Superiority Theory.” Its modern adherents include Roger Scruton, who analyses amusement as an “attentive demolition” of a person or something connected with a person. “If people dislike being laughed at,” Scruton says, “it is surely because laughter devalues its object in the subject’s eyes.”21

In linking Plato, Hobbes, and Scruton with the term “Superiority Theory,” we should be careful not to attribute too much agreement to them. Like the “Incongruity Theory” and “Relief Theory,” which we’ll consider shortly, “Superiority Theory” is a term of art meant to capture one feature shared by accounts of laughter that differ in other respects. It is not, like “Sense Data Theory” or “Dialectical Materialism,” a name adopted by a group of thinkers consciously participating in a tradition. All it means is that these thinkers claimed that laughter expresses feelings of superiority.

Discussing a philosopher under the “Superiority Theory,” furthermore, does not rule out discussing them under “Incongruity Theory” or “Relief Theory.” As Victor Raskin notes, the three theories “characterize the complex phenomenon of humor from very different angles and do not at all contradict each other–rather they seem to supplement each other quite nicely.”22 Jerrold Levinson explains how the accounts of laughter in Henri Bergson, Arthur Schopenhauer, and Herbert Spencer all had elements of both the Superiority and the Incongruity Theory, and how Immanuel Kant’s account, which is usually discussed under the Incongruity Theory, also has elements of the Relief Theory.23

We should also be careful in talking about theories of laughter and humor to distinguish different kinds of theories. Plato, Hobbes, and other philosophers before the twentieth century were mostly looking for the psychological causes of laughter and amusement. They asked what it is about certain things and situations that evokes laughter or amusement. Advocates of the Superiority Theory said that when something evokes laughter, it is by revealing someone’s inferiority to the person laughing.

Today, many philosophers are more concerned with conceptual analysis than with causal explanation. In studying laughter, amusement, and humor, they try to make clear the concepts of each, asking, for example, what has to be true of something in order for it to count as amusing. Seeking necessary and sufficient conditions, they try to formulate definitions that cover all examples of amusement but no examples that are not amusement. Of course, it may turn out that part of the concept of amusement is that it is a response to certain kinds of stimuli. And so conceptual analysis and psychological explanation may intertwine.

In this chapter I will discuss the three traditional theories mostly as psychological accounts, which is how they were originally presented. But we will also ask whether they could provide rigorous definitions of amusement and humor. Now back to the first of the three, the Superiority Theory.

If the Superiority Theory is right, laughter would seem to have no place in a well-ordered society, for it would undermine cooperation, tolerance, and self-control. That is why when Plato imagined the ideal state, he wanted to severely restrict the performance of comedy. “We shall enjoin that such representations be left to slaves or hired aliens, and that they receive no serious consideration whatsoever. No free person, whether woman or man, shall be found taking lessons in them.”24“No composer of comedy, iambic or lyric verse shall be permitted to hold any citizen up to laughter, by word or gesture, with passion or otherwise.”25

Those who have wanted to save humor from such censorship have followed two general strategies. One is to retain the claim that laughter expresses feelings of superiority, but to find something of value in that. The other is to reject the Superiority Theory in favor of one in which laughter and humor are based on something that is not anti-social.

The first approach has been taken by defenders of comedy since Ben Jonson and Sir Philip Sidney in Shakespeare’s time. Against the charge that comedy is steeped in drunkenness, lechery, lying, cowardice, etc., they argued that in comedy these vices are held up for ridicule, not for emulation. The moral force of comedy is to correct mistakes and shortcomings, not to foster them. In Sidney’s Defense of Poesie, the first work of literary criticism in English, he writes that, “Comedy is an imitation of the common errors of our life, which he [the dramatist] representeth in the most ridiculous and scornful sort that may be, so as it is impossible that any beholder can be content to be such a one.”26

A modern proponent of the view that laughter, while based on superiority, serves as a social corrective, was Henri Bergson in Laughter. His ideas about laughter grew out of his opposition to the materialism and mechanism of his day. In his theory of “creative evolution,” a nonmaterial “vital force” (élan vital) drives biological and cultural evolution. We are aware of this force, Bergson says, in our own experience–not in our conceptual thinking but in our direct perception of things and events. There we realize that our life is a process of continuous becoming and not a succession of discrete states, as our rational intellect often represents it. Real duration, lived time, as opposed to static abstractions of time, is an irreversible flow of experience. Now Bergson admits that abstract knowledge is useful in science and engineering, but when we let it dominate our thinking, we handle our daily experience in a rigid, repetitive way, treating...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Editor

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1: No Laughing Matter: The Traditional Rejection of Humor and Traditional Theories of Humor

- Chapter 2: Fight or Flight – or Laughter: The Psychology of Humor

- Chapter 3: From Lucy to “I Love Lucy”: The Evolution of Humor

- Chapter 4: That Mona Lisa Smile: The Aesthetics of Humor

- Chapter 5: Laughing at the Wrong Time: The Negative Ethics of Humor

- Chapter 6: Having a Good Laugh: The Positive Ethics of Humor

- Chapter 7: Homo Sapiens and Homo Ridens: Philosophy and Comedy

- Chapter 8: The Glass Is Half-Empty and Half-Full: Comic Wisdom

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index