- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Monitoring the Critically Ill Patient

About this book

Monitoring the Critically Ill Patient is an invaluable, accessible guide to caring for critically ill patients on the general ward. Now fully updated and improved throughout, this well-established and handy reference guide text assumes no prior knowledge and equips students and newly-qualified staff with the clinical skills and knowledge they need to confidently monitor patients at risk, identify key priorities, and provide prompt and effective care.

This new edition includes the following five new chapters:

- Monitoring the critically ill child

- Monitoring the critically ill pregnant patient

- Monitoring the patient with infection and related systemic inflammatory response

- Monitoring a patient receiving a blood transfusion

- Monitoring pain

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Recognition and Management of the Deteriorating Patient

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

At the end of this chapter the reader will be able to:

- discuss the importance of prevention of in-hospital adverse events

- identify the clinical signs of impending or established deterioration

- discuss the role of outreach and medical emergency teams

- discuss the importance of education and training in relation to the deteriorating patient.

INTRODUCTION

Critically ill patients are not necessarily located within intensive care or high dependency units (ICU and HDU), but are frequently managed within ward areas. There is irrefutable evidence to confirm that early identification and timely management of the deteriorating patient, may negate the need for transfer to these units and ultimately improve outcomes (Jones et al. 2007; NICE 2007). The literature states that, antecedents to deterioration are present in up to 80% of patients before an adverse event, cardiac arrest, unplanned ICU admission or death occurs (Kause et al. 2004). This is postulated to be because of both the inability to either recognise deterioration, and/or to act on it promptly and appropriately, compounded by existing poor communication channels (Schein et al. 1990; Franklin and Matthew 1994). Nurses, by definition, are at the forefront of monitoring and recognising deteriorating patients which, in turn, relies on appropriate monitoring and accurate interpretation of findings, accompanied by timely action. If patients are permitted to progress without prompt and appropriate management, adverse events will occur with associated poor survival rates.

The aim of this chapter is to understand the recognition and management of the deteriorating patient.

PREVENTION OF IN-HOSPITAL ADVERSE EVENTS

In-hospital adverse events have been defined as an unintended injury or complication resulting in prolonged length of stay, disability or death, not attributed to the patient’s underlying disease process alone but by their health-care management (Baba-Akbari Sari et al. 2006; de Vries et al. 2007). The causes of this have been classified into three subthemes (NPSA 2007):

1. Failure to measure basic observations of vital signs

2. Lack of recognition of the importance of worsening vital signs

3. Delay in responding to deteriorating vital signs

The prevalence of adverse events has been estimated at between 3% and 17% of all hospital admissions, with resulting high human and financial costs (Baba-Akbari Sari et al. 2006). The most serious adverse events classified are unplanned admission to an ICU, cardiac arrest or death, 50% of which are estimated to be preventable (de Vries et al. 2007).

Survival to Discharge from In-Hospital Cardiopulmonary Arrest

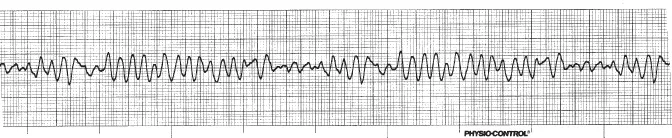

In the UK, overall less than 20% of patients who have an in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest survive to discharge (Meaney et al. 2010). These survival rates are also dependent upon the location and time of day at which they occur (Herlitz et al. 2002; Peberdy et al. 2008). Most of these survivors will have received prompt and effective defibrillation for a monitored and witnessed ventricular fibrillation (VF) arrest (Fig. 1.1) or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT), caused by primary myocardial ischaemia (Resuscitation Council UK 2010). Survival to discharge in these patients is very good, even as high as 37%) (Meaney et al. 2010).

Fig. 1.1 Ventricular fibrillation (coarse).

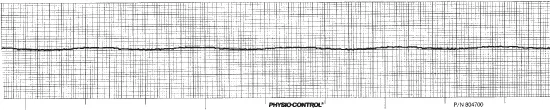

Unfortunately, most in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrests are caused by either asystole (39%) (Fig. 1.2) or pulseless electrical activity (PEA) (37%) (i.e. no pulse, but an ECG trace that would normally be expected to produce a cardiac output, (Fig. 1.3) Both of these non-shockable rhythms are associated with a very poor outcome (12% and 11% respectively – Meaney et al. 2010; Resuscitation Council UK 2010). These arrests are usually not sudden nor are they unpredictable: cardiopulmonary arrest usually presents as a final step in a sequence of progressive deterioration of the presenting illness, involving hypoxia and hypotension (Resuscitation Council UK 2010). In some studies it has been alleged that patients with abnormal vital signs before cardiac arrest have improved survival rates, compared with those who have normal vital signs, thus indicating the preventability of cardiac arrests (Skrifvars et al. 2006; Peberdy et al. 2008). Patients who experience cardiac arrest with non-shockable rhythms have a reduced chance of survival, so a vital approach that is likely to be successful is prevention of the cardiopulmonary arrest if at all possible. For this prevention strategy to be successful, early recognition and effective treatment of patients at risk of cardiopulmonary arrest are paramount. This strategy may prevent some cardiac arrests, deaths and unanticipated ICU admissions (Nolan et al. 2005). The statistics are irrefutable in that antecedents are present in 79% of cardiopulmonary arrests, 55% of deaths and 54% of unanticipated ICU admissions (Kause et al. 2004).

Fig. 1.2 Asystole.

Fig. 1.3 Pulseless electrical activity (PEA)/sinus rhythm.

Suboptimal Critical Care

In a seminal study (McQuillan et al. 1998), it was demonstrated that the management of deteriorating inpatients in the UK is frequently suboptimal.

Two external reviewers assessed the quality of care in 100 consecutive unplanned admissions to ICU:

- Twenty patients were deemed to have been well managed and 54 to have received suboptimal management, with disagreement about the remainder.

- Case mix and severity of illness were similar between the groups, but the ICU mortality rate was worse in those whom both reviewers agreed received suboptimal care before ICU admission (48% compared with 25% in the well-managed group).

- Admission to ICU was considered late in 37 patients in the suboptimal group. Overall, a minimum of 4.5% and a maximum of 41% of admissions were considered potentially avoidable.

- Suboptimal care contributed to morbidity or mortality in most instances.

- The main causes of suboptimal care were considered to be failure of organisation, lack of knowledge, failure to appreciate clinical urgency, lack of supervision and failure to seek advice. Junior staff frequently fail to recognise deterioration and appreciate the severity of illness and, when therapeutic interventions are implemented, these have often been delayed or are inappropriate. The management of deteriorating patients is a significant problem, particularly at night and at weekends, when responsibility for these patients usually falls to the on-call team whose main focus is on a rising tide of new admissions (Baudoin and Evans 2002).

Despite gaining criticism for alleged methodological weakness, this groundbreaking study was the catalyst for many other reviews and studies pertaining to the management of the deteriorating patient and the recognition of clinical antecedents.

Even more disturbingly, earlier studies of events leading to ‘unexpected’ in-hospital cardiac arrest indicate that many patients have clearly recorded evidence of marked physiological deterioration before the event, without appropriate action being taken in many cases (Schein, et al. 1990; Franklin and Matthew 1994).

Deficiencies in critical care management frequently involve simple aspects of care, e.g. failure to recognise and effectively treat abnormalities of the patient’s airway, breathing and circulation, incorrect use of oxygen therapy, failure to monitor the patient, failure to ask for help from senior colleagues, ineffective communication, lack of teamwork and failure to use treatment limitation plans (McQuillan et al. 1998; Hodgetts et al. 2002).

The ward nurse is uniquely positioned to recognise that the patient is starting to deteriorate and to call for appropriate...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Foreword

- Preface

- Contributors

- 1 Recognition and Management of the Deteriorating Patient

- 2 Assessment of the Critically Ill Patient

- 3 Monitoring Respiratory Function

- 4 Monitoring Cardiovascular Function 1: ECG Monitoring

- 5 Monitoring Cardiovascular Function 2: Haemodynamic Monitoring

- 6 Monitoring Neurological Function

- 7 Monitoring Renal Function

- 8 Monitoring Gastrointestinal Function

- 9 Monitoring Hepatic Function

- 10 Monitoring Endocrine Function

- 11 Monitoring Nutritional Status

- 12 Monitoring Temperature

- 13 Monitoring Pain

- 14 Monitoring a Patient Receiving a Blood Transfusion

- 15 Monitoring the Patient with Infection and Related Systemic Inflammatory Response

- 16 Monitoring the Critically Ill, Pregnant Patient

- 17 Monitoring the Critically Ill Child

- 18 Monitoring During Transport

- 19 Record Keeping

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Monitoring the Critically Ill Patient by Philip Jevon,Beverley Ewens,Jagtar Singh Pooni in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Nursing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.