- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Horticultural Reviews, Volume 39

About this book

Horticultural Reviews presents state-of-the-art reviews on topics in horticultural science and technology covering both basic and applied research. Topics covered include the horticulture of fruits, vegetables, nut crops, and ornamentals. These review articles, written by world authorities, bridge the gap between the specialized researcher and the broader community of horticultural scientists and teachers.

Information

Chapter 1

Frankincense, Myrrh, and Balm of Gilead: Ancient Spices of Southern Arabia and Judea

Abstract

Ancient cultures discovered and utilized the medicinal and therapeutic values of spices and incorporated the burning of incense as part of religious and social ceremonies. Among the most important ancient resinous spices were frankincense, derived from Boswellia spp., myrrh, derived from Commiphoras spp., both from southern Arabia and the Horn of Africa, and balm of Gilead of Judea, derived from Commiphora gileadensis. The demand for these ancient spices was met by scarce and limited sources of supply. The incense trade and trade routes were developed to carry this precious cargo over long distances through many countries to the important foreign markets of Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, Greece, and Rome. The export of the frankincense and myrrh made Arabia extremely wealthy, so much so that Theophrastus, Strabo, and Pliny all referred to it as Felix (fortunate) Arabia. At present, this export hardly exists, and the spice trade has declined to around 1,500 tonnes, coming mainly from Somalia; both Yemen and Saudi Arabia import rather than export these frankincense and myrrh. Balm of Gilead, known also as the Judaean balsam, grew only around the Dead Sea Basin in antiquity and achieved fame by its highly reputed aroma and medical properties but has been extinct in this area for many centuries. The resin of this crop was sold, by weight, at a price twice that of gold, the highest price ever paid for an agricultural commodity. This crop was an important source of income for the many rulers of ancient Judea; the farmers' guild that produced the balm of Gilead survived over 1,000 years. Currently there is interest in a revival based on related plants of similar origin. These three ancient spices now are under investigation for medicinal uses.

KEYWORDS: Apharsemon; Boswellia spp.; Commiphora spp.; Judaean balsam; olibanum; spice trade; traditional medicine

I. Spices and the Spice Trade

Traditionally, spices have had many important uses. Ancient cultures discovered the medicinal and therapeutic value of herbs and spices as well as their ability to enhance food flavors, and incorporated the burning of incense as part of religious and social ceremonies. Currently spices are used mainly as condiments but are also important in traditional medicine, perfumes, cosmetics, and special therapies.

Frankincense, myrrh, and balm of Gilead, three highly regarded biblical spice plants, will be emphasized in this chapter. Frankincense and myrrh were available in the biblical period only in limited parts of southern Arabia and the Horn of Africa. Due to the high demand for these spices, trade routes were developed to carry this precious burden over long distances through many countries to their foreign markets (Keay 2006). Balm of Gilead (tzori Gilead in Hebrew) is described in the Bible as the gift that the Queen of Sheba gave to King Solomon. In Judea, it was grown around the Dead Sea for about 1,500 years and achieved fame due to its aroma and medicinal properties. This chapter reviews these three ancient spice plants from a historical, horticultural, and pharmaceutical perspective, emphasizing the trade and routes from the Arabian Peninsula to the foreign markets in the Middle East and southern Europe.

A. Early History and Economic Importance

Spices and perfumes are mentioned in the records of ancient Sumer, which developed in the region of Mesopotamia around 3000 BCE. The Sumerian word for perfume is made up from the cuneiform signs representing “oil” and “sweet.” From that early period, and for millennia afterward, spices were added to natural oils to produce perfumes. The Sumerian song “The Message of Lu-dingir-ra to His Mother” refers to “a phial of ostrich shell, overflowing with perfumed oil” (Civil 1964). During the Bronze Age, the consumption of perfumes was confined to the upper and ruling classes. Perfume makers are known to have operated in Mesopotamia in the palace of Mari as early as the 18th century BCE (Bardet et al. 1984; Brun 2000). A growing body of archaeological evidence indicates that the volume of trade between Arabia and the surrounding areas accelerated during the Assyrian Empire. The increased use of drugs of herbal origin in medicine instead of employing surgery was encouraged in Mesopotamia, perhaps because the Code of Hammurabi threatened amputation if the surgeon was unsuccessful and found responsible (Rosengarten 1970). Assyrian documents record a growing interaction with the peoples of the Arabian Peninsula due to Assyrian attempts to control and capitalize on trade emanating from southern Arabia during the fifth century BCE.

Archaeological evidence of trade between southern Arabia and the Mediterranean coast has been found as early as the eighth century BCE in Tel Beer Sheva and Arad in Judea and includes the first appearance of alabaster containers and small limestone incense altars (Singer-Avitz 1996, 1999). The containers were a preferred means of storing and transporting raw incense resins, according to the Roman writer Pliny (Bostock 1855, Book 36, Chapter 60). New archaeological findings also indicate commercial relationships between southern Arabia and Judea, along the Incense Road. Much commercial activity existed in the Beer Sheva Basin, serving this trade during the seventh century BCE. In Tel Beer Sheva, several covers used for sealing the alabaster containers were found, as well as a stone object bearing the inscription of Cohen “priest” in a South Arabian language (Zinger-Avitz 1999). At Kuntillet Ajrud, located on the Incense Road from Eilat to Gaza, Ayalon (1995) found drawings and inscriptions in two buildings and a large assemblage of Judean and Israelite tools on sites along this incense road. These were dated to the end of the ninth century BCE. Singer Avitz (1996) describes an altar, dated to the eighth century BCE, excavated at Tel Beer Sheva, decorated with a one-humped camel. This trade was greatly expanded at the end of the eighth century BCE under the Assyrian kingdom; its track was through the Edomite Mountains and the south of Judea, where security could be controlled. The Assyrians established several fortifications and commercial centers there, such as Ein Hatzeva south of the Dead Sea, Botzera near Petra, Tell el-Kheleifeh (Ezion Geber) at the northern end of the Red Sea, and other sites along the Mediterranean Sea near Gaza (Finkelstein and Silverman 2006). A broken ceramic seal (7 × 8 cm) found in Bethel with the south Arabian inscription Chamin Hashaliach, in south Arabian letters of that period, was estimated to date from the ninth century BCE(Van Beek and Jamme 1958). The archaeologists (Hestrin and Dayagi-Mendels 1979; Dayagi-Mendels 1989) suggested that the seal meant Chamin the messenger.

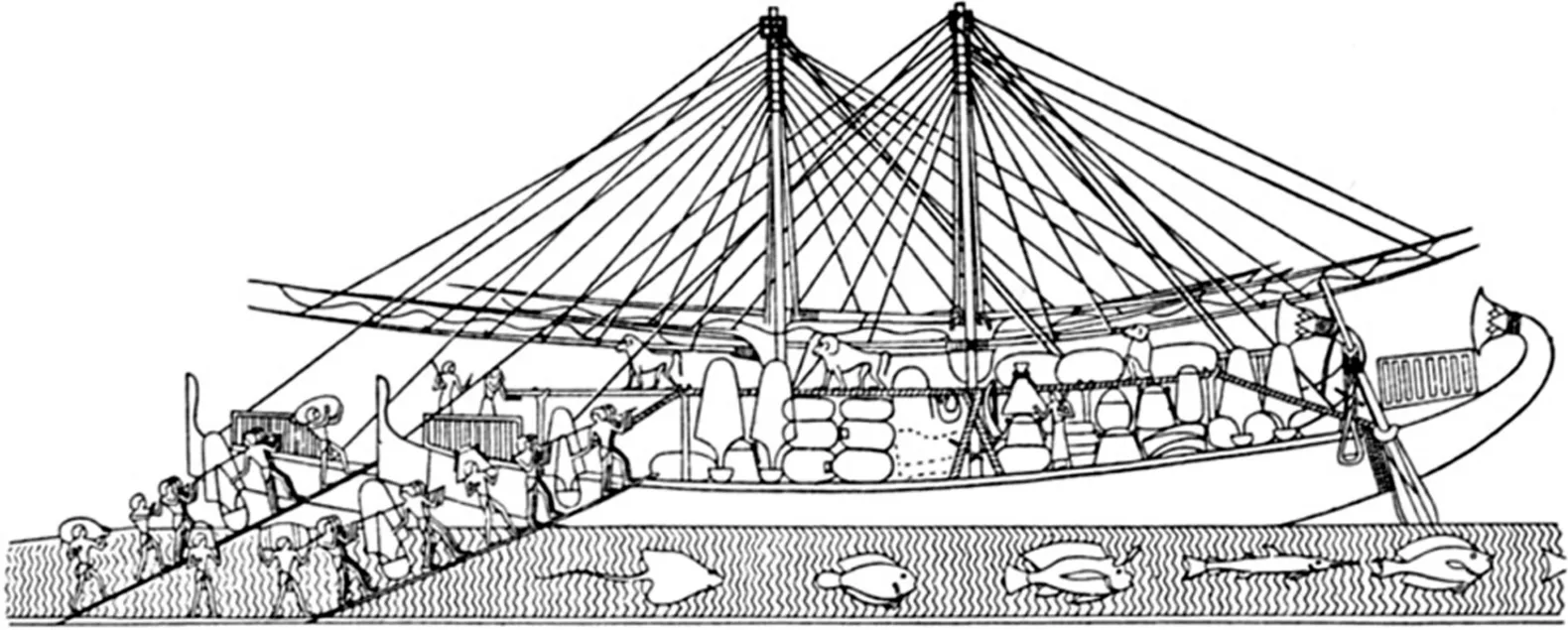

The ancient Egyptians used spices for their religious ceremonies that they purchased from the Land of Punt, long thought to be in the Horn of Africa (Kitchen 1993). At the beginning of the third millennia BCE, pharaohs went to great lengths to obtain spices, particularly myrrh, from other climes, since they were not grown locally. References to the importation of myrrh to Egypt from Punt, appear as early as the fifth dynasty ca. 2800 BCE under King Sahure and King Isesi; later there were expeditions under Mentuhotep III in 2100 BCE and under Amenenhat II and the Sesostris dynasty. Since the price of these spices was exorbitant, the Queen Pharaoh Hatshepsut organized an expedition to Punt about 1500 BCE to investigate the option of importing the spice plants into Egypt. The famous depictions (Fig. 1.1) of the expedition of Queen Hatshepsut (1473–1458 BCE) are recorded on the walls of the temple at Deir-el-Bahri (Lucas 1930; Phillips 1997). Five ships loaded with many treasures are depicted in the Temple in Thebes. One ship has 31 young trees that some scholars believed to be frankincense in tubs (Hepper 1969; Zohary 1982; Dayagi Mendels 1989). However, Groom (1981) believed them to be myrrh, as, according to his opinion, depictions of trees at that period were mainly schematic, presenting an image rather than a specific plant, and he referred also to the opinion of most previous experts that these trees were myrrh. Some scholars, however, find the trees on the Punt reliefs too conventionally drawn to be of any help in identifying them (Nielsen 1986).

Fig. 1.1. Queen Hatshepsut's expedition in 1500 BCE leaving Punt, northeast coast of Africa, with myrrh plants destined for Egypt. (Source: Singer et al. 1954.)

According to George Rawlinson (1897), the Egyptians entered the incense forests and either cut down the trees for their exuded resin or dug them up. Specimens were carried to the seashore and placed upright in tubs on the ships' decks, screened from sun by an awning. The day of transplanting in Egypt concluded with general festivity and rejoicing. Seldom is any single event of ancient history so profusely illustrated as this expedition, but there is no documentation for the growth of myrrh or frankincense in Egypt following this import. Recently, Punt has been identified as Eritrea and eastern Ethiopia, based on work of Nathaniel Domino and Gillian Leigh Moritz of the University of California, Santa Cruz, with oxygen isotope tests carried out on the fur of two ancient Egyptian mummified baboons imported by Hatshepsut and compared to baboons found in other countries. The isotope values in baboons in Somalia, Yemen, and Mozambique did not match. It was estimated that the mummified baboons dated from about 3,500 years ago, when Hatshepsut's fleet sailed to Punt and brought them back as pets (American Scientist 2010).

Spices, an important part of Egyptian life, were used extensively on a daily basis. The Egyptian word for myrrh, bal, signified a sweeping out of impurities, indicating that it was considered to have medicinal and, ultimately, spiritual properties (Schoff 1922). Ancient Egyptians regularly scented their homes and were commanded to perfume themselves every Friday (Ziegler 1932). Idols were regularly anointed with perfumes, and incense became an important element in religious ceremonies; prayers were believed to be transported to the gods by the smoke of incense rising upward (Ziegler 1932). Every large Egyptian temple contained facilities for producing and storing perfumes (Brun 2000). The Egyptians ground the charred resin into a powder called kohl, which was used to make the distinctive black eyeliner seen on many females and males too in Egyptian art.

B. Spices in Ancient Israel

The most important spices used in religious ritual in ancient Israel were:

balm of Gilead, called also Judaean balsam, Hebrew—tzori, nataf, or Apharsemon (Exodus 30:34)

onycha, Hebrew—tziporen or shchelet (Exodus 30:34)

galbanum, Hebrew—chelbna (Exodus 30:34)

frankincense or olibnum, Hebrew—levonah (Exodus 30:34)

myrrh, Hebrew—mor (Exodus 30:23)

cassia, Hebrew—kida or ktzeeha (Psalms 45:8)

spikenard, Hebrew—shibolet nerd (Song of Solomon 1:12)

saffron, Hebrew—karkom (Song of Solomon 4:14)

costus, Hebrew—kosht (Critot 6:71, Babylonian Talmud, Yoma 41:74, Jerusalem Talmud)

calamus, Hebrew—klufa (Song of Solomon 4:14)

cinnamon, Hebrew—kinamon (Song of Solomon 4:14)

The identification of these 11 spices was described and discussed in detail by Amar (2002) showing the existing different versions with their exact botanical ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication: Kim E. Hummer

- Contributors

- Chapter 1: Frankincense, Myrrh, and Balm of Gilead: Ancient Spices of Southern Arabia and Judea

- Chapter 2: Advances in the Biology and Management of Monosporascus Vine Decline and Wilt of Melons and Other Cucurbits

- Chapter 3: Ornamental Grasses in the United States

- Chapter 4: Mediterranean Stone Pine: Botany and Horticulture

- Chapter 5: Pointed Gourd: Botany and Horticulture

- Chapter 6: Physiology and Functions of Fruit Pigments: An Ecological and Horticultural Perspective

- Chapter 7: Ginger: Botany and Horticulture

- Chapter 8: Annatto: Botany and Horticulture

- Subject Index

- Cumulative Subject Index

- Cumulative Contributor Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Horticultural Reviews, Volume 39 by Jules Janick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Horticulture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.