eBook - ePub

Infectious Disease Management in Animal Shelters

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Infectious Disease Management in Animal Shelters

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Infectious Disease Management in Animal Shelters is a comprehensive guide to preventing, managing, and treating disease outbreaks in shelters. Emphasizing strategies for the prevention of illness and mitigation of disease, this book provides detailed, practical information regarding fundamental principles of disease control and specific management of important diseases affecting dogs and cats in group living environments. Taking an in-depth, population health approach, the text presents information to aid in the fight against the most significant and costly health issues in shelter care facilities.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Infectious Disease Management in Animal Shelters by Lila Miller, Kate F. Hurley, Lila Miller, Kate Hurley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Veterinary Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section 1

Principles of Disease Management

1

Introduction to Disease Management in Animal Shelters

SHELTER MEDICINE AS A SPECIALTY

The development of shelter medicine as a valued component of veterinary science reflects a variety of trends, including increased value placed on animals and a desire to seek alternatives to euthanasia as a response to companion animal homelessness; greater resources and sophistication on the part of animal-sheltering organizations, which create unprecedented opportunities for the design of quality facilities and health-care programs; and an explosion in the amount of evidence -based knowledge available to guide best practices for shelter animal care.

Although veterinarians have been working with shelters for years, it has only recently been acknowledged that this is a very complex field requiring special expertise. The first formal shelter medicine class at a veterinary college was offered by Cornell University in 1999; there are now shelter medicine programs, courses, and residencies offered at several universities. Many major veterinary conferences offer lectures in shelter medicine as well. There is an Association of Shelter Veterinarians whose membership is growing daily. As interest in the field steadily increases, more studies are being conducted to determine better ways of managing the health and welfare of shelter animals.

Roles of veterinarians in shelters

Veterinarians work with shelters in a variety of capacities as volunteers, employees, or consultants. The range of authority can be very broad. They may be on the high end of the chain of command as shelter directors or board members, or they may enter the shelter merely to provide per diem surgical or medical services. Many veterinarians fall somewhere in the middle as regular or part-time employees in charge of the health-care program.

Employment and consulting opportunities for shelter veterinarians are rising, and these opportunities represent rewarding and challenging options for professional practice. However, currently only a small percentage of veterinarians have a specialized background or expertise in this area. There is a great need to expand learning opportunities so that veterinarians may better serve shelter populations.

Herd health approach to shelter medicine

Simply stated, shelter medicine is herd health medicine for companion animals. The design of a comprehensive program to control, manage, and reduce the transmission of disease in animal shelters is a challenge for the veterinary professional. Current traditional clinical veterinary education focuses either on the design of cost-effective herd health protocols that emphasize disease prevention and maximize the production of animal products for food or that deliver sophisticated and potentially costly health care to individual companion animals. Shelter medicine requires a blend of these two approaches. Often the care of each individual shelter animal is best served by rigorous attention to the wellness of the group as a whole. When disease transmission is prevented, individual animals are spared serious illness that otherwise might not be treatable. When the population as a whole is healthy, more resources are available for those individuals requiring an additional level of care.

Another key historical difference in the two approaches to clinical practice revolves around the emotional bond and value attached to companion animals that do not exist to the same degree in large animal agricultural practice. This bond has a major impact on the ability to deliver science and evidence-based management recommendations to shelters. In the past, euthanasia was the primary tool for managing population numbers and disease in shelters, just as slaughter is often used to manage disease in large animal herds. The increasing rejection of the routine use of euthanasia by animal shelters can be traced to a number of factors, the human – animal bond being at the forefront. Although animal welfare groups may complain that companion animals are considered “disposable,” many people view them as family members. The same unprecedented interest in applying the latest medical advances to improve the health and well-being of companion animals applies to shelter animals as well.

Shelter medicine seeks to combine herd health management strategies and principles with individualized animal care in a way that has not been done before. Confronting shelter medical problems can therefore present a true quandary for the well-meaning companion animal practitioner who lacks a background in either herd health or shelter management. Conversely, the large animal herd health practitioner who tries to apply traditional methods of outbreak management in a shelter (i.e., depopulation, closing the herd down, and testing all newcomers) will find that in many cases these strategies will be rejected outright. This textbook was conceived to help veterinary professionals sort through the haze to find effective, acceptable, and workable solutions to disease problems and to promote health and wellness in shelter environments.

Unique aspects of the s helter environment

One might argue that the design of herd health care for companion animals is not new, and that shelter medicine does not require all this attention. It is true that some of the basic principles of disease control that have been utilized for managing kennels, catteries, and research laboratories apply in shelters, but significant differences exist. The goals of breeding and research facilities can be uniformly defined, whereas animal shelters have unique goals and challenges related to their varied missions. Differences and fluctuations in funding, resources, philosophy, training, governance, and even community attitudes towards the shelter all play roles in the functioning and priorities of shelter health programs. Husbandry practices must often be implemented in shelters that have never been applied in any other communal housing situation, thereby forcing shelter veterinarians to be innovative, resourceful, and courageous in their decision making.

The disease prevention component of shelter medicine is integrated into a complex health-care program that extends far beyond simple recommendations about vaccinations and deworming. The range of knowledge and experience required to design a comprehensive shelter wellness program can be quite daunting. The health aspect of animal sheltering intersects with virtually every other program within a shelter, including adoptions, volunteer programs, foster care, stray animal management, zoonotic disease control, cruelty investigations, and even design of the shelter building itself. In other words, few if any shelter programs are not directly or indirectly affected by animal health considerations. In addition to an in-depth knowledge about infectious disease, shelter veterinarians must be knowledgeable about several other disciplines, including sanitation, animal behavior, nutrition, husbandry, stress reduction, data collection, veterinary forensics, high-volume, high-quality spay/neuter techniques, and so much more. For more comprehensive information about shelter medicine and shelter operations, the reader is referred to Shelter Medicine for Veterinarians and Staff by Miller and Zawistowski, and to www.sheltermedicine.com, the Web site of the Koret Shelter Medicine program at the University of California, Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine. Additional resources are listed in Appendix 1.1. Most of the information in this introductory chapter will be covered in more detail in Chapters 2, 3, and 4 on wellness, outbreak management, and sanitation, and in each of the various other chapters. This chapter serves as an overview and introduction to the concepts necessary for designing an effective health program.

SHELTER MISSIONS AND GOALS

As noted above, an understanding of the shelter’s mission is critical to the design of an effective shelter health program. A medical program that keeps animals healthy but fails to help meet the major goals of the organization – such as adoption of animals, increasing spay/neuter rates in the community, or reducing euthanasia – cannot be considered a complete success. Even advising on management of an outbreak or treatment of an individual animal requires an understanding of that particular shelter’s goals and resources, both in general and for that individual animal or situation.

The American Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) Community Outreach department estimates there are between 4,000 and 6,000 animal shelters in the United States alone. It is a mistake to assume that all shelters have identical goals. Although there is often an overlap in the provision of services, shelters tend to fall into two basic categories: they are either municipal shelters charged primarily with animal control responsibilities, or private, nonprofit shelters. Some communities have multiple shelters, both municipal and private, while others do not have shelters at all.

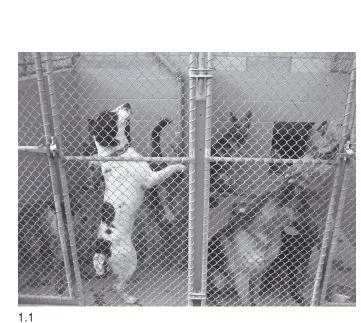

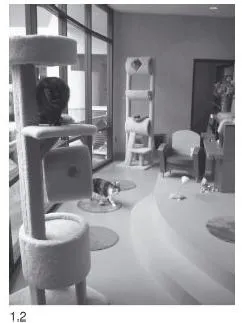

Figures 1.1. and 1.2. Shelter resources, design, and mission vary widely. Figure 1.1 shows an overcrowded colony kennel for dogs.

Figure 1.2 shows an enriched communal space for cats.

Not all shelters focus on adoption and rehabilitation of homeless animals. The allocation of municipal shelter resources may emphasize stray animal capture, protection of public health, complaint resolution, and law enforcement, whereas the private animal welfare organizations may dedicate larger expenditures to vaccinate, deworm, test for disease, treat, and neuter animals for rehoming. However, there is an increasing tendency for municipal as well as private shelters to work toward an increased adoption rate; seek alternatives to euthanasia as a strategy for disease management; and develop programs that emphasize public outreach and prevention of problems that lead to relinquishment. There is great variation within private shelters as well, ranging from those that provide lifelong sanctuary to a limited number of animals to those that accept all animals presented and euthanize those they are unable to place, and many variations on these strategies. Some of the different types of shelters are described in more detail below.

Just as it is important not to judge clients by their appearance, the breed of their pet, or the vehicle they drive, it is not advisable to make assumptions about shelter philosophy or resources based on shelter type, title, location, or history. Priorities may change and opportunities emerge with changes in management or philosophy. Even the smallest or poorest shelter may prioritize adoption, utilize progressive spay/neuter, volunteer, foster or other programs, or pursue alternatives to euthanasia for management of disease. Even if these possibilities are not available immediately, shelters may incorporate them into future plans. Therefore, all options should be offered to shelters and ideal standards explained, just as they would be for any patient. Figures 1.1 and 1.2 depict shelter housing for dogs and cats.

Municipal shelters

It is a common belief that most municipal shelters operate chronically overcrowded, underfunded programs located in dilapidated facilities in undesirable sections of the community. While this model does exist, animal sheltering has undergone a fundamental change in many communities over the past 20 years as the human–animal bond strengthens and society becomes less tolerant of animal abuse and neglect. Shelters of all types have experienced increased internal and external motivation to upgrade the quality of care they provide. There has been a varied response to this pressure: many communities are renovating, retrofitting, and building new facilities with the latest innovations, consulting with veterinarians, expanding staff and services, etc. Veterinary expertise is required to effectively implement many of these changes.

Municipal shelter functions historically focused on stray animal pickup, control of dangerous animals, including quarantines of animals that may have bitten someone, capture of free-roaming animals, nuisance complaints, investigation of animal cruelty complaints, handling of wildlife, etc. They may also offer adoptions, low-cost spay/neuter and vaccination clinics, humane education, and an assortment of volunteer, foster care and other community programs. Most municipal shelters are mandated to accept all animals regardless of their capacity to find homes or take appropriate care of them, and utilize euthanasia regularly for animals that cannot be safely placed for adoption and as a tool to manage the population numbers as well as disease.

Private shelters

Private shelters are generally chartered as 501(c)3, not-for-profit organizations; they are privately funded and their policies are often set by elected or volunteer boards of directors. Private shelters may incorporate the words “humane society” or “SPCA” in their titles, but most private shelters operate independently and are not related to each other, nor are shelters titled “SPCA” related to the ASPCA. Some private shelters contract to provide animal control services to local government entities (county or city), although an increasing number have relinquished animal control contracts to focus on adoption, spay/neuter, behavior, and humane education programs.

One of the latest ongoing trends in animal sheltering is for humane societies to adopt policies known as “no kill,” meaning they will not euthanize adoptable animals for lack of space to house them. This has a major impact on animal care programs: “no kill” organizations or limited admissions facilities may restrict their admissions and hold animals for longer periods, which can create unique challenges for maintaining animal health and mental wellness. Studies in United States shelters have shown that the longer animals remain in a shelter, the more likely they are to become sick, although a recent study completed in shelters in the United Kingdom showed the opposite trend with respect to feline upper respiratory infection (Edinboro, Janowitz, et al. 1999; Edinboro, Ward, et al. 2004; Edwards, Coyne, et al. 2008). This illustrates the impact that variations in shelter environments, management practices, and even cultural attitudes can have on animal health.

A great deal of variation can be found even within the scope of private shelters with similar titles. It should be noted that few if any descriptive terms can be assumed to have consistent meaning across all shelters. The term “no kill” is just one example. Some shelters that use this term do perform some euthanasia, while some shelters that follow similar policies to those commonly found in “no kill” shelters (e.g., they limit intake and/or do not perform euthanasia for population control) do not use the term.

Other types of shelters

Not all shelters can be categorized as either strictly municipal or private. In addition to private shelters that accept the contract to provide municipal services, some municipal shelters solicit private donations to provide services not mandated or paid for by their contractual arrangement with the municipality. Other foster care and rescue groups may work out of private homes or focus on a specific breed, age, or special needs animals. They often work closely with shelters to rescue animals that can be rehabilitated and placed for adoption if provided with veterinary and behavioral care that cannot be offered by the shelter. A limited number of sanctuaries also exist that will provide lifelong care for animals that cannot be successfully or safely adopted.

REGULATION OF SHELTERS

There is little, if any, accountability of shelters to any particular entity. There is no parent organization to which all shelters belong: the ASPCA and the Humane Society of the U.S. (HSUS) are autonomous, independent organizations that do not oversee or run local SPCAs, humane societies, or other animal rescue or adoption organizations. Most states do not regulate shelters, nor does the federal government. Only a few states have minimum standards of care for animals in shelters. Regulations pertaining to shelters are often limited to providing guidelines for euthanasia and mandating holding periods for stray animals and bite cases. However, the shelter veterinarian should become familiar with relevant local laws, as there is an increasing trend towards greater regulation and scrutiny of many aspects of shelter practice.

Requirements for data reporting

While a few states do require reporting of certain statistics related to animal intake and disposition, this is not generally the case. Even the number of shelters operating in the United States is unknown. In addition to the lack of reliable data regarding the number of shelters in this country, the lack of reporting requirements makes it difficult to accurately determine the number of animals admitted or euthanized in shelters, or to establish norms for disease rates or other important measures of shelter animal health. However, while national or international figures remain elusive, individual shelters and communities are becoming increasingly sophisticated in tracking important data related to the well-being of animals in their communities. With the widespread use of computerized, and in some cases Web-based, shelter database programs, pooled data collection and analysis from multiple shelters may become increasingly possible in the future.

SHELTER CHALLENGES

Any veterinary professional who is working with a shelter must have an understanding of the obstacles and challenges the shelter faces in order to design an effective and comprehensive program that combines preventative health-care strategies with wellness protocols. Whatever the shelter’s particular mission, one goal of every shelter should be to provide a clean, healthy, and safe environment that supports the maintenance and improvement of the health of all of its residents, regardless of the length of their stay or ultimate fate. Some of the issues that must be dealt with in order to achieve these goals will be touched upon briefly in this chapter.

Shelter resources

Shelters, regardless of their mission or type, are often limited in the resources they can offer to provide animal control and welfare services. Human and animal services must often compete for sparse municipal funding, and private fundraising efforts may be insufficient to meet the targets and needs of the shelter program. Veterinarians can best serve shelters by advising on allocation of limited resources for maximization of shelter animal health in the context of the shelter’s overall goals and mission. Even with limited funding, shelters can maintain a healthy environment for the animals with meticulous attention to management of population numbers, good sanitation, prompt isolation of diseased animals, stress reduction, and other practices described in this chapter and elsewhere in this text.

Veterinarians should take a broad view when advising on resource allocation in shelters. In many cases, when all costs are considered, prevention of illness is not only more humane for the animals and preferable for public health, it is more cost effective than the alternative. Even apart from ethical considerations, a modest investment in vaccination, diagnostic testing, or sanitation will be amply repaid if more animal lives are saved and more animals are adopted as a result: adoption fees can offset some of the costs of care, while the costs associated with euthanasia and disposal can be substantial. Thus the best approach for animal health and adoption can also prove to be a sound financial choice, especially when preventive measures are emphasized.

Fortunately, many of the practices that enhance shelter animal health are no more costly than less effective practices. For example, as described in Chapter 5 on vaccination and immunology, vaccinating animals at the time of admission is far more likely to confer protection than vaccinating them a few days or even a few hours later, and costs no more. In some cases, best practices are actually less expensive than the alternative. For instance, Chapter 4 on sanitation describes in-residence or “spot” cleaning as a preferred method of cleaning for cat cages. This takes less time and utilizes fewer costly chemicals than more intensive daily disinfection, while potentially reducing stress and limiting disease transmission among cats.

If resources are so limited that basic practices to protect animal health cannot be implemented, this should ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Section 1: Principles of Disease Management

- 1: Introduction to Disease Management in Animal Shelters

- 2: Wellness

- 3: Outbreak Management

- 4: Sanitation and Disinfection

- 5: Canine and Feline Vaccinations and Immunology

- 6: Pharmacology

- 7: Necropsy Techniques

- Section 2: Respiratory Diseases

- 8: Feline Upper Respiratory Disease

- 9: Canine Kennel Cough Complex

- 10: Canine Distemper Virus

- 11: Canine Influenza

- Section 3: Gastrointestinal Diseases

- 12: Feline Panleukopenia

- 13: Canine Parvovirus and Coronavirus

- 14: Internal Parasites

- 15: Bacterial and Protozoal Gastrointestinal Disease

- Section 4: Dermatological Disease

- 16: Dermatophytosis

- 17: Ectoparasites

- Section 5: Other Diseases

- 18: Rabies

- 19: Feline Leukemia Virus and Feline Immunodeficiency Virus

- 20: Feline Infectious Peritonitis

- 21: Vector-Borne Diseases

- 22: Heartworm Disease

- 23: Zoonosis

- Index

- Eula