![]()

CHAPTER 1

HEENT Pitfalls

Alisa M. Gibson and Sarah K. Sommerkamp

Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

Introduction

Emergencies affecting the ear, nose, and throat (ENT) constitute a large component of chief complaints seen in urgent care centers. The majority of these patients have benign conditions that can be managed on an outpatient basis. Some seemingly innocuous complaints can be reflective of diseases that pose significant risk of morbidity and possibly mortality. As with most diseases, the key to differentiating between minor and dangerous conditions is the history and physical examination. A huge spectrum of pathology can manifest in the head and neck, and the management of this patient group can be overwhelming for an individual practitioner. In this chapter, we present key facts, highlight the pitfalls inherent in diagnosing these conditions, and offer pearls intended to facilitate their management.

Eye

Pitfall | Failure to ensure that patients with epithelial defects are treated with appropriate antibiotics and seen by an ophthalmologist within 24 hours

A wide variety of eye complaints are encountered by acute care providers. Differentiation between corneal abrasions, corneal ulcers, and corneal foreign bodies can be difficult. The majority of patients with any of these conditions present with eye pain and a gritty or foreign body sensation. Visual acuity may be affected, depending on the location of the defect, so testing and documenting visual acuity are essential, as they are in all patients with eye complaints. Acute monocular visual loss may signify a more dangerous condition, such as central retinal artery occlusion, central retinal vein occlusion, acute angle closure glaucoma, or retinal detachment or a central nervous process (stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), or multiple sclerosis (MS)). Patients with any of these signs should be referred to an emergency department.

Patients with suspected corneal epithelial defects should have a full eye examination. A slit lamp is preferred to Wood’s lamp. The instillation of analgesic and/or cycloplegic drops will significantly relieve the patient’s symptoms and increased his/her ability to tolerate the examination, but these drops should not be used if globe rupture is suspected. Fluorescein staining is mandatory for the evaluation of a corneal defect and to rule out herpes keratitis. Defects in the epithelial surface appear as a stain that does not clear with blinking. The size and position of any defect(s) should be documented. Punctate defects, which appear in a circular pattern, are sometimes seen in contact lens wearers, particularly after prolonged wear. Larger defects with a crater formation are ulcers.

Parallel vertical abrasions should raise suspicion for a foreign body under the lid. When this type of injury is detected, the patient’s eyelid should be everted to allow further assessment. Without treatment, and over time, the vertical abrasions will coalesce and form an ulcer. Foreign bodies may also be lodged directly on the corneal surface. In many cases, they can be removed with a cotton swab or irrigation, but if that procedure is unsuccessful, removal with a needle or burr may be necessary and should be done only by someone with specific training. Metal foreign bodies may lead to the development of a rust ring, which should only be removed by an ophthalmologist [1].

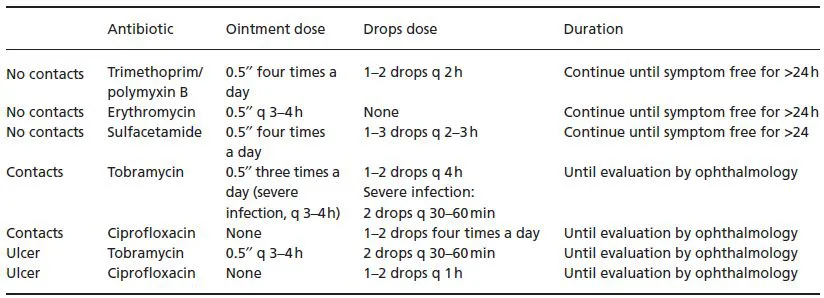

Table 1.1 Treatment of corneal abrasions, ulcers, and foreign bodies

Data from Silverman MA, Bessman E. Conjunctivitis: treatment and medication. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/797874-overview. April 27, 2010.

KEY FACT | Foreign bodies or rust rings can wait up to 24 hours for removal by an ophthalmologist.

The immediate treatment of corneal abrasions, ulcers, and foreign bodies is similar (Table 1.1). Simple abrasions that are smaller than 3 mm do not require follow-up as long as no foreign body is present, the patient’s visual acuity is normal, and symptoms resolve within 24 hours [2]. However, if there is any doubt, referral to an ophthalmologist is reasonable. All other defects should be seen by a specialist within 24 hours. Antibiotics, which may be prescribed as either ointment or drops, should be administered to all patients with epithelial defects. Ointment is generally preferred (particularly for children) because it is easier to apply, stays in place longer, and lubricates the eye. However, ointments are not well tolerated by most adults because they obscure vision and interfere with activities such as driving and reading. Drops are dispersed by the natural lubrication mechanisms of the eye. Firmly squeezing the eye shut for 5 minutes after administration will close the drainage ducts and increase penetration. Contact lens wearers with corneal abrasions require antipseudomonal antibiotic coverage and should be advised to refrain from wearing their contacts until they are cleared to do so by an ophthalmologist. All patients with corneal ulcers also require antipseudomonal antibiotic coverage.

Patients with painful corneal abrasion may require systemic narcotics. Ophthalmic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be prescribed, but are expensive. Topical anesthetics such as tetracaine should never be prescribed or given to patients for use at home, as repeated use may be associated with the development of ulcers. Tetanus status should be updated as needed. Eye patching has not been shown to be effective in accelerating healing. In fact, because it might worsen the infection and thus lengthen the time to recovery, it is not recommended [3].

KEY FACT | All patients with corneal ulcers require antipseudomonal antibiotic coverage.

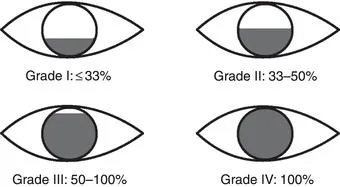

Pitfall | Failure to identify high-riskpatients with hyphema who require inpatient admission

A hyphema is a collection of blood in the anterior chamber. Patients typically present with eye pain and pupillary constriction. Visual acuity is variably affected, based on the amount of blood present. The condition most commonly results from trauma, but it can appear spontaneously in patients with sickle cell anemia or bleeding dyscrasias. Hyphemas are graded on a scale of I to IV, based on the amount of blood present (Figure 1.1). The hyphema grade is important to the clinical management and disposition of the patient. Visual acuity should be documented and globe rupture ruled out before a complete eye examination – including measurement of intraocular pressure – is performed. Concomitant ocular and bony injuries are common in patients with hyphema. Computed tomography (CT) may be indicated for patients with facial trauma. Laboratory studies to identify coagulopathy (complete blood count (CBC), prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT)) should be done in patients with known or suspected bleeding disorders. After globe rupture is excluded, ultrasound, if available, can be used to evaluate the eye for retinal detachment, lens damage, an intraocular foreign body, and choroidal hemorrhage [4].

All patients with hyphema are at risk of long-term complications such as synechiae and angle recession, cataracts, and delayed bleeding, and therefore must be followed up daily by an ophthalmologist. Certain patients have risk factors that necessitate emergent consultation and might warrant admission: these include sickle cell disease, bleeding dyscrasias (such as anticoagulation or hemophilia), potentially open globes, young age, and grade III or IV hyphemas [5–7]. Healthy compliant patients with none of the above risk factors who have hyphemas that fill less than 50% of the anterior chamber can be discharged home with ophthalmologic follow-up within 12 to 24 hours. Interventions are focused on an avoidance of re-bleeding and prevention of intraocular hypertension. Patients should be placed with the head of the bed elevated 30 degrees, in a dim quiet room. An eyeshield should be placed, and removed only for examination. The patient should be placed on bed rest with bathroom privileges and should not read or watch television as those activities may cause pupillary constriction and obstruct outflow. Analgesia with topical cycloplegics may be used, and systemic narcotics are frequently also required. NSAIDs should be avoided because of their associated bleeding risk. Nausea and vomiting should be treated aggressively since they can raise intraocular pressure. These instructions should be clearly communicated to any patient being discharged.

Throat

Sore throat is an extremely common complaint. It has a broad differential, ranging from viral illness to life-threatening conditions such as epiglottis and retropharyngeal abscess. In the majority of cases, these conditions can be differentiated by the history and physical examination. The fear of “strep throat” brings many people to acute care centers. Most people do not realize, however, that infection with Group A Streptococcus (GAS) is responsible for fewer than 10% of cases [8]. Other bacterial causes of acute pharyngitis include gonorrhea, diphtheria, and Fusobacterium. Viruses account for the majority of cases of pharyngitis. Typical viral pathogens include adenovirus, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalorvirus (CMV), the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and influenza.

KEY FACT | Viruses account for the majority of cases of pharyngitis. Group A Streptococcus is responsible for fewer than 10% of cases.

Pitfall | Indiscriminate use of antibiotics for acute pharyngitis

Treatment of GAS pharyngitis with antibiotics can reduce the duration of illness by 1 or 2 days, decrease the risk of transmission, and prevent nonsuppurative complications (rheumatic fever and post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, which are both rare among adults in the United States) and suppurative complications (peritonsillar abscess, sinusitis, retropharyngeal abscess). Those treatment goals, although well intentioned, lead to a great deal of prescriptions for unwarranted antibiotics. Overuse of antibiotics is typically thought of as hazardous to the population at large in terms of increasing resistance patterns, but it can also be dangerous for the individual. Disruption of the normal flora puts the patient at risk of superinfections by organisms such as Candida and Clostridium difficile and makes the antibiotic less effective for that patient for a full year [9]. The decision to prescribe antibiotics can be based on the individual patient’s condition or by a combination of culture, the rapid streptococcal antigen test (RSAT), and the Centor criteria (see below). The use of culture is often impractical in an acute care practice, given that it can take 2 or 3 days to get results. The RSAT is 70–90% sensitive and 90–100% specific [10–12]. To perform this test, vigorously swab both tonsils and the posterior pharynx. Obtaining an adequate sample is crucial, as sensitivities correlate directly to inoculum size [13]. A positive test result is helpful, but a negative result does not rule out the disease. Many facilities do not have RSAT capabilities, so the diagnosis of GAS pharyngitis is frequently based on clinical criteria.

The Centor criteria constitute a clinical decision rule designed to assist with the diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis. The four criteria are tonsillar exudates, swollen, tender anterior cervical nodes, the absence of a cough, and a history of (or current) fever. If none of these criteria is present, the likelihood of a culture being positive for the presence of GAS is 2.5%. The likelihood of a positive test result increases with the number of c...