This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A new study of Shakespeare's life and times, which illuminates our understanding and appreciation of his works.

- Combines an accessible fully historicised treatment of both the life and the plays, suited to both undergraduate and popular audiences

- Looks at 24 of the most significant plays and the sonnets through the lens of various aspects of Shakespeare's life and historical environment

- Addresses four of the most significant issues that shaped Shakespeare's career: education, religion, social status, and theatre

- Examines theatre as an institution and the literary environment of early modern London

- Explains and dispatches conspiracy theories about authorship

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Who Was William Shakespeare? by Dympna Callaghan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism of Shakespeare. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

THE LIFE

1

WHO WAS WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE?

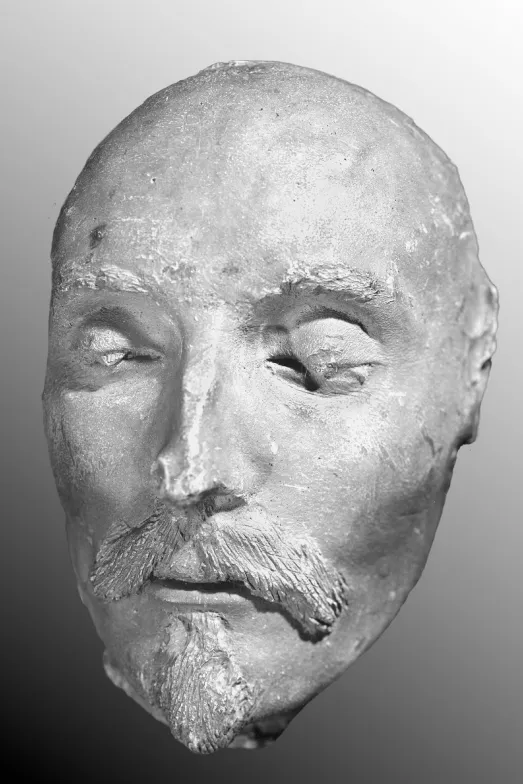

In 1841 a canon of Cologne Cathedral, Count Francis von Kesselstadt, died. His passing promised to answer definitively the question that is the subject of this book: Who was William Shakespeare? This was because among the count’s dispersed possessions was a death mask bearing the label “Traditionen nach Shakespeare,”1 and marked on the reverse “Ao Dm. 1616,” the year of Shakespeare’s death (see Figure 1.1). Believed to have been purchased in England by one of the count’s ancestors, who had been attached to an embassy at the court of James I, the curiosity was recovered in 1849 from a secondhand shop in Darmstadt and brought from Germany to the British Museum by a man named Dr Ludwig Becker as the death mask of none other than England’s national poet.2 Unfortunately, the unpainted death mask is not an image of Shakespeare, but the belief that it was such epitomizes the persistent desire to capture Shakespeare’s identity.

Figure 1.1 The Kesselstadt Death Mask.

Image reproduced by kind permission of Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Darmstadt.

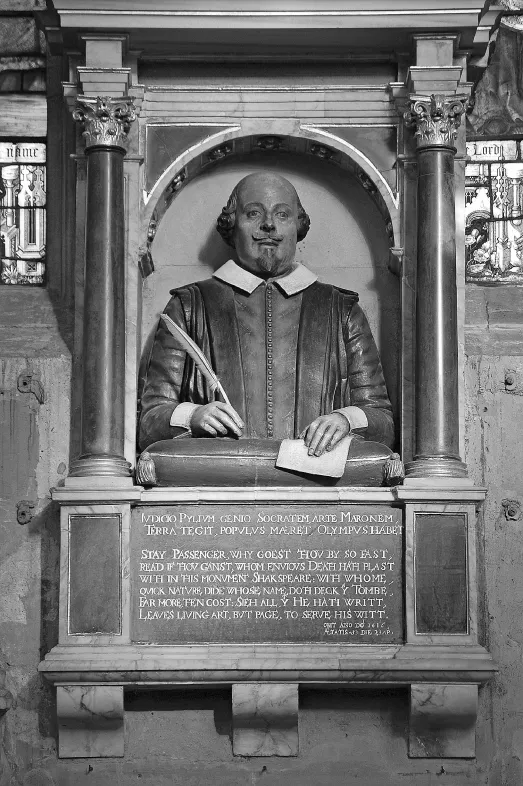

The death mask is perhaps what Shakespeare ought to look like, unlike the figure mounted on the north wall of the chancel in Holy Trinity Church at Stratford-Upon-Avon in 1622, pen and paper in hand (see Figure 1.2). Apart from the engraving executed by Martin Droeshout on the First Folio (the collection of Shakespeare’s plays compiled in 1623), this unprepossessing figure is the only reliably authentic image of Shakespeare left to posterity. It is singularly unfortunate, then, that the figure on the funeral monument in Holy Trinity, as the critic Dover Wilson once remarked, looks “like a self-satisfied pork butcher.”3 Dissatisfaction with the bust grew almost directly in proportion to Shakespeare’s posthumous reputation, which gathered increasing momentum through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. By the nineteenth century, fascination with the Kesselstadt death mask was excited by what was felt to be the inadequacy of the Holy Trinity monument. When A.H. Wall, who had spent many years as a professional portrait artist, addressed the Melbourne Shakespeare Society in 1890 in a paper called “Shakespeare’s Face: A Monologue on the Various Portraits of Shakespeare in Comparison with the Death Mask …” he described the monument as “a failure,” “clumsy,” “crude, inartistic, and unnatural.”4

Figure 1.2 The Shakespeare memorial bust from Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-Upon-Avon. © John Cheal “Inspired Images 2010.”

Whatever the alleged deficiencies, the Stratford monument (and it is, admittedly, no great work of art) must have offered at least a minimally adequate likeness of Shakespeare because his wife, Anne, and daughters, Judith and Susanna, his sister, Joan, as well as other relatives, friends, and denizens of Stratford who knew the poet well would have seen it every time they went to church. The dissatisfaction Wall articulates, however, extends beyond artistic merit to the ideological reconstruction of Shakespeare’s face by the Romantics as a serene and high-browed poetic countenance that probably bears little or no similarity to Shakespeare’s actual face – which the monument no doubt creditably, if not very artfully, resembles. In contrast, the marble statue at University College Oxford by Edward Onslow Ford of the handsome young poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, who drowned in 1822, looks exactly as a dead poet should (see Figure 1.3). Little wonder, then, that by the time the Kesselstadt death mask was discovered, many prominent artists and experts were eager to proclaim the likeness to be truly Shakespeare’s. After the “discovery” of the death mask, Ronald Gower, opined, “Sentimentally speaking, I am convinced that this is indeed no other but Shakespeare’s face; that none but the great immortal looked thus in death, and bore so grandly stamped on his high brow and serene features the promise of an immortality not of this earth alone.”5 Although, periodically, claims for its authenticity resurface (the most recent advocate being Dr Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel of the University of Mainz in 2006), the death mask’s authenticity has now been wholly discredited, and it does not any longer form part of the British Museum collection, having been consigned to the provincial obscurity of the Grand Ducal Museum in Darmstadt, Germany. David Piper of the National Portrait Gallery in London has queried whether the artifact even genuinely dates from the period. He claims that if it had been an authentic Jacobean artifact, “it must be the only death mask of a subject other than royalty known to have been made let alone survived at this period.”6 What the death mask unequivocally demonstrates, however, is the degree to which ideas about authorship inherited from the nineteenth century still shape ideas and understandings of Shakespeare’s life and work. It is, after all, the disparity between the Shakespeare to be found in the historical record and exalted ideas about dead poets that have led Oxfordians and others to dismiss the real, historical Shakespeare as the mere “man from Stratford.”

Figure 1.3 Memorial Sculpture of Percy Bysshe Shelley by Edward Onslow Ford.

Photograph by Dr Robin Darwall-Smith, FSA, FRHistS. Used by the permission of the Master and Fellows of University College Oxford.

We might expect that Shakespeare would have at the very least merited the services of one of the greatest artists of his time, some English Michelangelo: perhaps Nicholas Stone, who sculpted the magnificent full-length statue of John Donne in his shroud for St. Paul’s cathedral in 1631. Stone was already receiving important commissions by 1614 when he was only fifteen years old, and two years later, in the year of Shakespeare’s death, he was appointed to royal service. Or perhaps Maximilian Colt, who completed the marble sculpture of Elizabeth I for Westminster Abbey, and who in 1608 was appointed master carver to the king, would have been a worthy recipient of the commission. Despite the disparagement heaped on the artistic inadequacies of Shakespeare’s funeral monument, its artist, Gheerart Janssen (sometimes anglicized as Gerard Johnson), the son of a Dutch sculptor of the same name who had settled in London around 1567 and established a notable family business near the Globe theatre in Southwark, was, in fact, a perfectly respectable choice to execute the likeness of the poet. The Janssens had sculpted the handsome monument for Edward Manners, the third Earl of Rutland, who died in 1587. This work is on a vastly larger and grander scale than Shakespeare’s effigy. It includes evidence of the scope of Rutland’s political power in the kneeling alabaster figure of Rutland’s granddaughter, Elizabeth, whose marriage he had arranged to none other than the grandson of Elizabeth’s chief minister, William Cecil, Lord Burghley. A second tomb (which also interned his wife Elizabeth) was made for Edward’s brother, John, the fourth Earl of Rutland, who died only a year later. For this aristocratic charge – two tombs and four paintings erected at St Mary the Virgin in Bottesford, Leicestershire – Janssen the elder was paid two hundred pounds in 1590. When Roger, the fifth earl died, the Janssens were employed again for a recumbent alabaster effigy of the earl and his wife. Shakespeare probably knew about these tombs because the sixth Earl of Rutland, Francis Manners, was a friend of Shakespeare’s patron, the Earl of Southampton. Indeed, Rutland and Southampton had been brought up together as wards of Lord Burghley. Further, Rutland hired Shakespeare along with Richard Burbage for forty-four shillings apiece to design an impresa – a chivalric device of an emblem with a motto – which would be displayed on the combatant’s shield, for the Accession Day Tilt, an annual jousting tournament, of 1613.

A comparison between the full-sized, elaborate, recumbent effigies of the earls of Rutland replete with ancillary figures and Shakespeare’s modest edifice is instructive. Shakespeare was a poet, a playwright, and a player, not an aristocrat, and his funeral monument, commemorating a life begun in Stratford, where he was baptized in 1564 and buried in 1616, is an instance in which art accurately mirrors life, or at least social status. This is exactly how early moderns thought things should be. For, as John Weever observed in Ancient Funerall Monuments (1631), “Sepulchers should be made according to the qualitie and degree of the person deceased, that by the Tombe one might bee discerned of what ranke he was living.”7 The image in Holy Trinity Church, reflects rather accurately, then, the status of a poet and playmaker in early modern England, even one of Shakespeare’s unparalleled talent. By these standards, the bust is appropriate, and thus successfully fulfills the purpose for which it was intended. Indeed, Nicholas Rowe records in his 1709 volume of Shakespeare’s works that in 1634 an early visitor, a Lieutenant Hammond, described it as a “neat Monument.”8 The image in fact tells us a great deal about what it meant to be an author at a time when no one then living could ever have envisaged that the gifted Warwickshire native would vie with Elizabeth I as the most important figure of late sixteenth-century England.

Shakespeare’s immediate family almost certainly commissioned the monument, and they probably employed Gheerart Janssen because he had executed the full-length, recumbent alabaster effigy of fellow-Stratfordian, John Combe, which also lies in Holy Trinity Church. Combe was the friend who left “Mr. William Shackspere five pounds” in his will, and when the poet himself died, he bequeathed his sword to another member of the Combe family, Thomas, John’s nephew. Shakespeare’s image is just the torso and is made of the cheaper, local Cotswold limestone and would have been considerably less expensive than Combe’s more elaborate monument that cost sixty pounds in 1588. However, what most distinguishes the monuments of these friends is that Combe is depicted lying down in peaceful repose whereas Shakespeare is alert, upright, and at work. This posture is not unique to Shakespeare but simply accords with representational convention. The chronicler of London, John Stow, for example, is also thus depicted. Yet, that Shakespeare, almost completely bald, whiskered, and wearing a red doublet and a black sleeveless gown, holds the tools of his trade in his hands – a quill and paper – conveys the sense that even Shakespeare’s afterlife would be in some way about writing rather than resting in peace.

The bizarre phenomenon of the Kesselstadt death mask, however, promised something more than a face better fitted to Shakespeare’s plays than Janssen’s rendering. Had it indeed proved genuine, the mask would constitute the material vestige of Shakespeare’s actual visual identity in a way that a mere sculpted depiction does not. What is more, the Janssen bust is one of only two verifiably authentic portraits of Shakespeare – the other being Martin Droeshout’s engraving on the First Folio.9 The yearning, represented by the death mask, for an image that would take us closer to Shakespeare is understandable in so far as his lineal descendants had died out before the end of the seventeenth century and there are no truly personal traces, such as diaries, letters, or possessions, not even the much-vilified second-best bed that Shakespeare bequeathed to his wife. Probably the closest we get to Shakespeare-the-man is his will, which is simply an inventory of his possessions and their disposal. Little wonder, then, that, even in the late twentieth century, Susan Sontag wished for an impossibly vivid connection with Shakespeare: “Having a photograph of Shakespeare would be like having a nail from the True Cross … , something directly stenciled off the real, like a footprint or a death mask.”10 The German mask had, in fact, promised precisely such a hallowed and evidentiary trace: red facial hair was still attached to the plaster on the inside.11

Thus, the fascination with Shakespeare’s image has persisted despite Ben Jonson’s famous verse directing readers to the works rather than the engraving on the First Folio: “Reader look / No...

Table of contents

- COVER

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- DEDICATION

- NOTE ON THE TEXT

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- PART I: THE LIFE

- PART II: THE PLAYS

- INDEX