![]()

1

Generalizing about Virgil: Dialogue, Wisdom, Mission

And behold I hear a voice… “pick it up and read it!”

Augustine (Confessions 8.12)

Literary code and genre dictate the nature of the tacit communication between the poet and the audience.

Charles Segal (from his introduction to Conte’s The Rhetoric of Imitation, 9)

Virgil wrote in code. The word “code,” as it occurs in the citation above, refers to poetic style and to the method by which a poet conveys meaning. Poetry is encoded through certain generic associations and allusive connections. Though originally composed for a scroll, Virgil’s poems have been preserved for us in the form of a book known as a “codex,” the shape of a book that we still use today. The Latin word codex (i.e., caudex, originally “bark,” later “book”) is the origin of the English words code and codex. The epic code that the reader confronts when reading Virgil was itself recoded when it was transferred from the ancient scrolls to codex.

Virgil composed three major poetic works, each in dactylic hexameters under the generic term epos (Greek “word”). Virgil’s works can thus be classified as three manifestations of epic code. Virgil’s earliest work, the Eclogues, is bucolic, to all appearances concerning the world of herdsmen; his second, the Georgics, is didactic, ostensibly on farming; his grand narrative, the Aeneid, is heroic. These distinctions within the code belonging to epos represent the first signposts on our journey through Virgil’s poetry.

Of Codes and Codices

To decipher Virgil’s code, the reader must begin by accessing the codex in its modern book form. The modern form is derived from ancient and medieval sources and such a history will be explored in the sixth chapter of this book. For the moment, however, let us consider one such manuscript as contributing to the history of Virgil’s text.

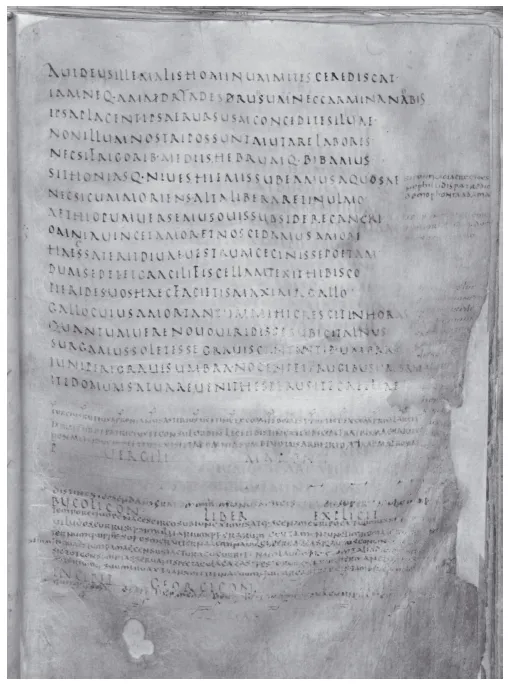

In the sixteenth century, an important manuscript came into the hands of Francesco I de’ Medici, and thus it came to be called Codex Mediceus. Francesco moved it from Rome to the seat of Medicean influence, Florence. Housed in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, this antique codex preserves emendations added in red ink by the fifteenth-century philologist Julius Pomponius Laetus (in Italian, Pomponio Leto).1 Prior to Leto, however, an early owner and editor of the manuscript had added a subscription in a tiny font at the end of the Eclogues, just before the opening of the Georgics (Figure 1.1):

Turcius Rufius Apronianus Asterius v(ir) c(larissimus) et inl(ustris) ex comite domest(icorum) protect(orum) ex com(ite) priv(atarum) largit(ionum)

ex praef(ecto) urbi patricius et consul ordin(arius) legi et distincxi codicem fratris Macharii v(iri) c(larissimi)

non mei fiducia set eius cui si et ad omnia sum devotus arbitrio XI Kal. Mai(as) Romae.2

(I, Turcius Rufius Apronianus Asterius, right honorable former member of the protectors of the [imperial] house and former member of private distributors of wealth ║and former prefect of the city, patrician and duly elected consul, read and punctuated this codex of my right honorable brother [viz. “friend”] Macharius, ║not because of any confidence in myself but because of my confidence in him, to whomsoever [i.e., my future reader?] I have also in every respect been devoted with regard to my judgment [i.e., my job of editing]; [inscribed] on April 21 at Rome.)

This subscription provides an important dating marker known as a terminus ante quem?3 Turcius Rufius Apronianus Asterius pored over the manuscript carefully, and his mysterious words – in the above translation the phrase “to whomsoever” is especially curious – offer tantalizing details. Like Leto years later, Apronianus would presumably have been doing his editing based on an earlier version that was one step closer to Virgil’s autograph (original manuscript). Apronianus’ encoding of the text is not simply the inclusion of this dedication but also his emendations and punctuation.

What is Apronianus trying to tell posterity in this subscription? First, he is attempting to say that, though he had earned the highest traditional Roman office, he was not a mere politician but was one who had a deep appreciation for Virgil and has painstakingly emended the text. That he had done so during his consulship – Rome’s high office instituted by Lucius Iunius Brutus in 509 bc – is obviously significant, as is the fact that he makes this subscription on April 21, the date of the annual Parilia festival, which was recognized as the birthday of Rome. The year ad 494 would have dated nearly one thousand years from the foundation of the Roman Republic. Thus, when Apronianus notes that he was a consul ordinarius (entering the office “on the appointed day” and thus, “duly elected”), he ties himself to the ancient, traditional office. The reference to the Parilia acknowledges Rome’s pre-Christian past, as Pales was a pagan deity connected with pastures. This addendum fittingly comes after the Eclogues and before the Georgics, both of which treat flocks.4 With this subscription, he accomplishes, then, a great deal, affirming the abiding value of ancient Rome’s greatest poet.

To emphasize his connection with traditional Roman values, Apronianus further states that he was the sponsor of traditional pagan Roman games. Yet we also know him as an editor of Christian devotional poetry. His family had been, since the time of Constantine, connected to the ruling class. A certain L. Turcius Apronianus held an urban prefecture, and his son replicated this achievement in 362. The fourth-century historian Ammianus (23.1.4) tells us that one of these was also a senatorial legate in Antioch under the emperor Julian.

Material evidence enhances our understanding of the family: two statue bases, found in the Campus Martius, held representations of Apronianus and his wife; these images may have come from their home there. The other side of the family lived on the Esquiline. Possibly to protect their wealth from the Gothic invasion of 410, some family member hastily buried heirlooms near the house. This treasure, which includes objects that show pagan influence, certainly belonged to the same family as our manuscript inscriber. Cameron concludes that the family consisted of both pagan and Christian members; the Christian branch was likely to have intermarried with non-Christians.5

Such a reconstruction of this family’s religious leanings suits our Apronianus, who both published an edition of Sedulius’ Christian poetic work Carmen Paschale and at the same time was an aficionado of Virgil, punctuating the manuscript that he obtained from his “brother” Macharius.6 When one is reading “Virgil,” one is reading a collated text indebted to editors such as Apronianus.

The coexistence of his family’s two cultural backgrounds – a family mosaic perhaps not so uncommon among contemporary aristocrats – suggests a workable interaction of pagan and Christian elements. Given his Christian affiliation, Apronianus’ subscription is important to the Virgilian tradition because that tradition has now become a blend of two religious cultures and his subscription is literally a Christian addendum to a long pagan tradition. His dedication to Virgil’s future readership shows his awareness of his transmission of Virgil in this codex, bearing witness to Apronianus not only as a significant editor but also as an important early reader of the text. Apronianus has thus encoded the text in such a way as to ensure that his manuscript of Virgil would be a part of the future, even if that should be a Christian future. In a sense, he buried in the pages of this manuscript an autobiographical nugget for posterity, as his forebear had buried the family treasure on the Esquiline.

Code of Readership

The reader who picks up a book and reads it opens a dialogue with the codex and, ultimately, with the code itself. Thus, the reader begins to interact with the text and its code; this interaction or negotiation with the text is “coded” because the reader is establishing his or her own code of readership while encountering Virgil’s epic code. The notion of a code moves in both directions: what we are calling epic code moves from the text to the reader, while what we are calling the code of readership represents the reader’s negotiation with the text. Such negotiation is assisted by the author, who “establishes the competence of the Model Reader, that is, the author constructs the addressee and motivates the text in order to do so. The text institutes strategic cooperation and regulates it.”7 The greater the appreciation that any reader has of the tradition, the closer he or she approximates the Model Reader and becomes equipped to negotiate the business of reading the text.

Though we shall never know fully what future reader Apronianus envisioned or what kind of reader Virgil had in mind, we can nevertheless establish a few characteristics for a Model Reader of any age. First, as any reader begins to approximate a Model Reader, he or she will increasingly acknowledge that a wider tradition informs Virgil’s text and, to the extent that he or she is able, begin to embrace that tradition. For example, the more knowledgeable the reader is of Homer, the deeper that reader’s understanding of the Aeneid will become. The Model Reader understands that the later author can best be understood in light of the earlier.

The second criterion for the Model Reader is some knowledge of the cultural milieu of Virgil’s lifetime. While the attribution of a rigid political agenda to Virgil is unproductive, one cannot hide from the fact that Virgil was cognizant of his own relevance within the poetic tradition and was aware that the Roman world was in the midst of a major transition.

Thirdly, the Model Reader must have respect for the text’s authorial voice. Apronianus seems to have shown such respect in dedicating his careful editorial work “in every respect” to his future reader or, possibly, God himself;8 he recognizes the importance of his place within a tradition that preserves Virgil’s authorial voice. All the discrepancies within the manuscripts notwithstanding – even those that may have been unwittingly introduced by Apronianus – the text known as “Virgil” still emerges, which the Model Reader seeks to understand in view of the tradition, in its historical context, and with respect for the integrity of the authorial voice. Conscientious readership does not preclude the reader’s response but qualifies it: the Model Reader engages in honest negotiation with the text.

Poetic Craft

Long before Virgil began his literary production in the late 40s bc, versifying was a matter of poetic craftsmanship. The etymology of the Latin word poeta, descended from a Greek word meaning “make” (poieo), implies such fashioning. The other Latin word for poet, uates, means “seer” or “prophet,” a metaphorical description that embodies poetic inspiration. Inspired by the Muses, the Roman poet opens a dialogue with his predecessors through allusion and cross-pollination of genres. This was especially true in Virgil’s time: the skilled poet engaged his predecessors through a process of imitation, emulation, and interpretation.9

Virgilian allusion is generally consistent with the practice of poetic reference called Alexandrian, developed in the Hellenistic period (323–327 bc) and characterized by emulative playfulness.10 Before that period, allusion had been, generally speaking, more imitative than emulative. The dictum that the plays of Aeschylus were “scraps from Homer’s banquet” is an old one, attributed to Aeschylus himself by third-century author Athenaeus (Deipnosophistae 8.347e). Aeschylus does not so much emulate Homer as avail himself of Homeric material, often expanding it. In the Hellenistic period something different begins to happen, as allusion effects a learned game, anticipating a reader with a code-breaking mentality. Alexandrian reference is not necessarily meant to be recognized immediately, for such allusive encoding is written for knowledgeable insiders or intended for discovery on a second or third reading.11 Now, commentary becomes erudite, response somewhat cryptic, and allusion often opaque, intended for readers “in the know.” To see where Virgil falls in this allusive spectrum, let us, before turning to his text, consider two examples outside his corpus. We shall see that Virgil’s Alexandrian style encompasses the kind of allusion seen in Greek poets such as Pindar.

Nearly half a millennium before Virgil, Pindar, the eminent poet of Boeotian Thebes, composed Olympian 14 to celebrate the Olympic victory of Asopichos, son of a deceased Boeotian nobleman. This poem is addressed to the Graces, the chief goddesses of the Boeotian city Orchomenos:

O Graces of Orchomenos, guardians of the ancient race of the Minyai, hear me when I pray. For through you all pleasant and sweet things are produced for mortals, if there is anyone wise, beautiful and famous. (14.4–7)

In a manner consistent with the classical form of allusion in his day, Pindar creates a communal mood for this poem by weaving into his text references to Hesiod, his Boeotian predecessor who had lived more than a century before him, specifically echoing Hesiod’s description of the Graces (Theogony 63–74).

Pindar uses the poetic character Echo to report to Kleodamos in the Underworld the positive developments regarding Asopichos:

In Lydian style of lays I have come, singing of Asopichos,

for your sake Aglaia, who in the Minyan land is victorious in Olympian games

Go, Echo, to the dark-walled abode of Persephone,

Bringing to his father the fair announcement,

so that when you see Kleodamos you may tell him of his son,

how in the famous vale of Pisa he crowned his hair with the glorious contests’ garlands. (14.17–24)

Echo metaphorically embodies the allusion to Hesiod, for Pindar “echoes” Hesiod. Pindar’s fame preserves Hesiod’s memory, just as Asopichos’ victory preserves his father’s good name in Boeotia. The local flavor of this ode also helps to connect Asopichos and Kleodamos, his deceased father, with that of Pindar and his poetic father-figure, Hesiod. Though Pindar’s allusion to Hesiod and his use of it could be said to anticipate Alexandrian practice, it is more general and, if somewhat intricate, not meant chiefly for readers in the know.12

A similar example can be seen in Euripides, who, about a third of the way through the Medea, refers to the celebrated bard Orpheus. Jason states that he would rather enjoy personal fame than great wealth or even “the capacity to sing songs sweeter than those of Orpheus” (543). Orpheus is the prototypical singer and exemplum of the faithful husband; his name in the mouth of Jason is thus incongruous and stinging, representative of Euripides’ ironic method.13

Such early references, though adroit, are not as sophisticated as Alexandrian allusion. By the beginning of the Roman imperial period, the practice of allusion, having passed through the Alexandrian filter, surpasses even Jason’s reference to Orpheus in Euripides’ Medea or Pindar’s expression of Boeotian loyalty to Hesiod in Olympian 14. Let us consider how it does so through two further examples.

The end of the first Georgic includes an interesting reference to the river Euphrates, which is based on a similar description of the Assyrian river in Callimachus:

I was singing of these things… while great Caesar thunders in war along the deep Euphrates and as victor gives laws throughout the willing nations and builds a road to Olympus. At that time sweet Parthenope was nursing me, Virgil, when I was flourishing in the pursuits of inglorious leisure. (1.559–64)

In this context, as Clauss has noted, the proximity ofwar (561) and peace (564) suggests that, after the battle of Actium, Virgil is stating that he “can avail himself of ignobile otium, the peace and leisure needed for non-military, georgic topics.”14 A few years earlier, Scodel and Thomas had noted th...