This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Providing a vital link between theory and practice, this unique volume translates the latest research data on the effectiveness of interventions for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) into practical guidance for education professionals working with ASD pupils.

- Reformulates new research data on interventions for ASD into guidance for professionals, drawing on the author's in-depth academic knowledge and practical experience

- Offers a comprehensive review of up-to-date evidence on effectiveness across a wide range of interventions for ASD

- Focuses on environmental factors in understanding ASD rather than outdated 'deficit' approaches, and discusses key issues in education provision such as inclusion

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Interventions for Autism by Phil Reed in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Education in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Autism Spectrum Disorders – What is the Problem?

The quest for the ‘holy grail’ of developing effective interventions to help people who have Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) has brought forth the usual clutch of quacks, charlatans and self-publicists, but mingled with the money-seeking snake-oil sellers are highly committed and professional practitioners and researchers, whose efforts have produced important innovations in the treatment of ASD. The many debates that have been produced in this quest for interventions have generated much heat, some little light, certainly much controversy and a great deal of confusion regarding what interventions are actually effective. The current work aims to untangle some of the mass of data regarding interventions for ASD and to provide some suggestions about the circumstances under which particular approaches may offer some help to the key people involved; that is, those affected by ASD, both directly themselves and through their close connection to somebody who is directly affected.

Autism Spectrum Disorders

The precise definition of ASD is and has been, in flux for 50 or more years. Recently, the diagnostic criteria for labelling the disorder have undergone yet another shift, from those contained in the previous Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) IV-TR, to those outlined in the new DSM-5. The nature of these criteria and some of the implications of these changes, will be discussed in Chapter 2, but it is safe to assert that ASD presents a range of complex and interacting behaviours and deficits that appear early in a person’s development and persist, sometimes in differing forms, throughout that person’s life impacting a wide range of their functioning. These characteristics mark out ASD from other more specific forms of psychological problems associated with childhood and make complex any intervention.

These issues will be covered later in terms of developing a characterization of the nature of ASD that presents for treatment (see Chapter 3), but, at this point, it is worth noting a few salient generalizations about the condition. For many, it is the types and quality of social and emotional interactions engaged in by people with ASD, as well as behavioural inflexibility and highly focused attention on aspects of their environment, that are central to its characterization. These key aspects of the disorder typically present together, making this a wide-ranging ‘syndrome’, with myriad potential causes – genetic, obstetric, physiological and even parenting. In itself, a disorder with multiple causations is often difficult to treat, but these primary problems are often connected with secondary or co-morbid problems for the individual with ASD, such as high levels of challenging behaviour, social isolation, anxiety and depression. The degree to which such secondary symptoms are present differs between each individual, both in the types of symptom present and also in their severity, making ASD a ‘spectrum’. Of course, these individual symptoms are not unique to ASD and it has been suggested that all share some of these ASD-typical traits – that is, there is a ‘broad autistic phenotype’ in the population. This may be true, but it is the presence of all problems together that characterize the disorder as ASD – a syndrome with a spectrum.

It is certainly the case that ASD cannot be recognized physically (despite some recent claims to contrary) and it is also true to say that ASD is found across the entire range of people in society. This consideration raises another issue: given this broad range of people with ASD and given the potential presence of these characteristics in us all, is it a problem to have ASD? This question touches on another, increasingly important, aspect of the theoretical discussion that it is important to raise early: that is, whether the ‘core’ elements of ASD are always to be regarded as ‘impairments’ that are in need of ‘treatment’. Indeed, some have even queried whether ASD should be ‘treated’ at all. It has been suggested that some of the behavioural and cognitive differences between people with and without ASD can sometimes confer an enhanced ability to the individual with ASD in some areas of performance (e.g. in terms of attention-based tasks requiring focus on detail) – albeit an ability at the expense of flexibility as circumstances change. However, it is equally important to note that there is by no means a consensus on this issue, either in the academic literature or among those individuals with an ASD themselves. The task of answering this question is made doubly difficult given the variation in behaviours and needs of people with ASD.

In framing a focused understanding of the scope of the present work, it may, thus, help to consider two questions related to these issues: (i) is having ASD a problem and (ii) if so, how and for whom? The first question is rather easier to answer from the perspective of a work on intervention, than from the perspective of a more theoretically based tome – quite simply, there are many, perhaps countless, individuals with ASD and their families who desperately need help – therefore, it is a problem for those people with ASD and for those people who their lives they touch, when it is a problem for them. To deny the existence of such a problem is wrongheaded and, to deny the treatment, is cruel, which is worse. As usual, there are very important provisos to add to this straightforward answer: not all people with ASD do require help and not all people with ASD require help with everything. Thus, interventions for ASD must be flexible enough to accommodate these considerations; that is to say, they must recognize that which was noted previously – that ASD is a spectrum and not a unitary disorder and that interventions will need to be tailored to suit different situations with different individuals. Together, these guiding tenets impact considerably on the focus to be taken regarding understanding the nature of ASD and the development of its interventions.

To answer the second question posed previously – ‘whose problem is ASD?’ – it can be said that it is not just a problem for the person with ASD, but it is a problem for and of, the community in which that person with ASD resides. The current text takes the view that an important contrast is made between the within-person disability model, which attempts to identify immutable causal structures within the person with ASD and a social-environmental approach, which suggest mutable functional connections between the person’s environment and their behaviours (see Chapter 3). Far too much attention and too many resources have been placed on the former view at the expense of the latter, especially when it is seen that almost all scientifically supportable interventions stem from the latter conceptualization of ASD.

Treating ASD

If ASD is to be considered as a problem to be treated, then it is worth saying a few brief words about the nature of ‘treatment’. There are a vast range of interventions now championed as being effective for ASD and the current work surveys those on which significant serious research has been conducted. These will be described throughout the text, but it is taken as a truth that it is possible to say that there are some interventions that are better than others and also that it is not in anybody’s best interests to accept the claim that any intervention is good merely if is offered and conducted well (Jordan et al., 1998). Too many times has it been suggested at conferences and gatherings of professionals that anything goes in this field. A consequence of the assumed need for a clear evidence-base tilts the approach of this book toward adopting a ‘medical model’ of evidence assessment – an approach that has met with considerable success in other areas of treatment – hence, the use of the term ‘treatment’ interchangeably with ‘intervention’ and in preference to currently more trendy re-labelling of ‘treatment’.

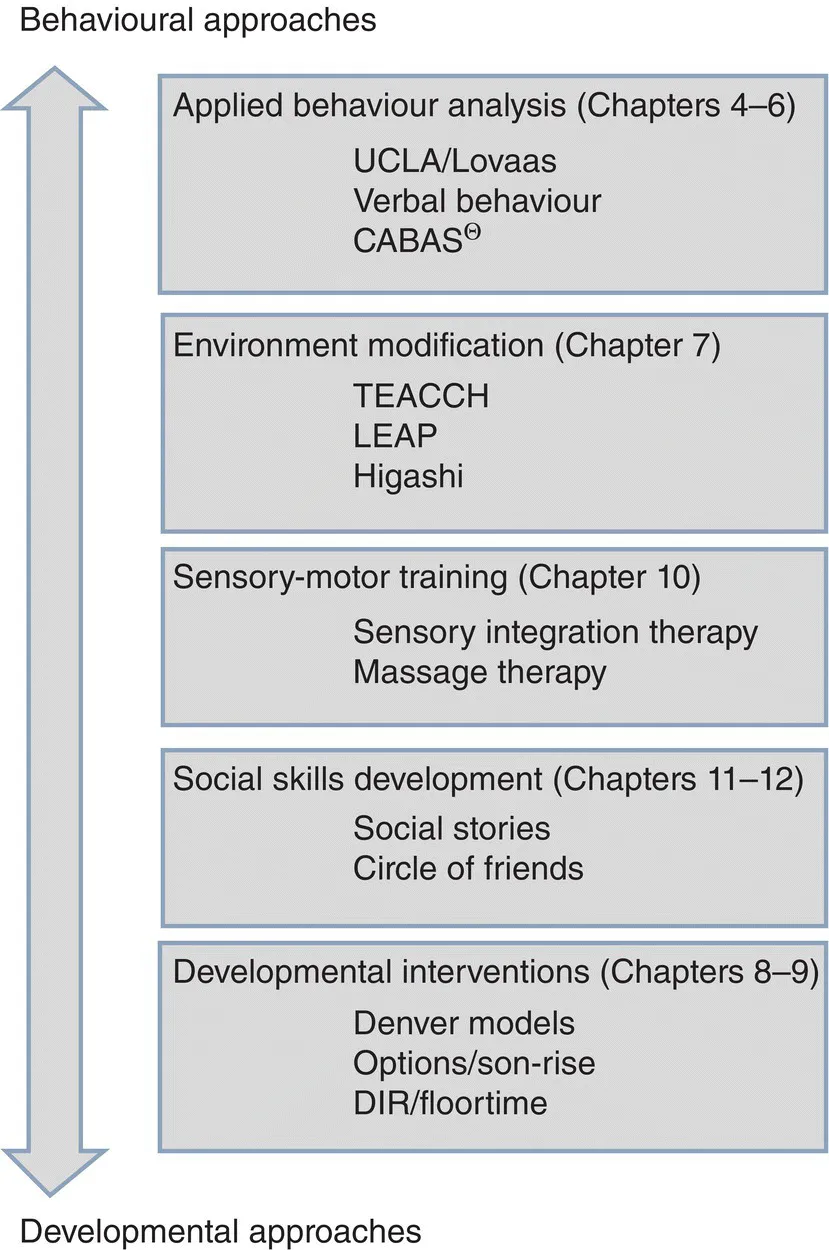

With this belief, the current work will take as ‘treatments’ those interventions that have made it out of the laboratory. This focus has the result of acting rather like a filter, determining which, out of the many potential interventions, will be discussed. Many interventions that have been developed purely in the laboratory, on the basis of particular theories, will not be addressed and neither will those that have been developed on the whim of individual practitioners. However, there are still many intervention programmes that pass this filter. Some of the history of interventions is presented in Chapter 3, where it can be seen that interventions for ASD have a longer history than might be expected. However, from the early 1970s onwards, larger numbers of interventions have emerged. For example, although Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) programmes (e.g. Lovaas, 1987; see Chapter 4) are often commented upon in the scientific and popular literature, approaches such as the Treatment and Education of Autistic and Related Communication Handicapped Children (Schopler & Reichler, 1971) and the Denver Health Sciences Programme (Rogers et al., 1986), emerged at least as early as ABA and the last few years have seen the development and proliferation of many more interventions for ASD. Many of these treatment types are mentioned in Figure 1.1, which presents a schematic representation of the interventions that several reviews have suggested as important (Odom et al., 2010; Ospina et al., 2008; Stahmer et al., 2005; Vismara & Rogers, 2010).

Figure 1.1 A schematic representation of a number of individual types of intervention programmes and their broad characterizations (based on Opsina et al., 2008).

The current filter applied to the selection of particular interventions to be considered also has a number of further components. The current survey addresses only those interventions that accept, as their central focus, the individual affected by an ASD. This sounds like a rather odd or obvious thing to state, but too many times the main focus of an intervention has been to support the underlying theory or philosophical beliefs from which the intervention was developed. To this end, the evidence, as it relates to the impact of interventions on the functioning of people with ASD and not how it supports this or that theoretical view of ASD, will be utilized. This approach reinforces two aspects already introduced into the discussion – in addition to the necessity of obtaining good evidence regarding the effectiveness of interventions, emphasis needs to be placed: firstly, on the functionality of the interventions – they must affect change, rather than adhere to any particular theory and secondly, on the essential individuality of people with ASD – the interventions must be adaptable to one of the most individual group of people. Needless to say, this will not be easy.

One way of summarizing these various aspects of the support to be provided by any good intervention is that they are all concerned with producing a better match between the abilities of people with ASD and the environment in which they are placed. This objective is well reflected in a quote from a person with Asperger’s syndrome reported by Baron-Cohen (2003, p. 180): ‘We are fine if you put us in the right environment. When the person with Asperger’s Syndrome and the environment match, the problem goes away… When they do not match, we seem disabled.’ That is, interventions need to be targeted at adapting the environment to the person in order to more effectively contact that person’s behaviours, develop their skills to their full potential and enhance their chances of success. It is argued in Chapter 3 that this form of treatment phil...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Autism Spectrum Disorders – What is the Problem?

- 2 Autism Spectrum Disorders

- 3 The Relationship of Theory and Interventions for ASD

- 4 Behavioural Approaches to ASD

- 5 Evaluation of Comprehensive Behavioural Interventions

- 6 Child Predictors for Comprehensive Behavioural Intervention Outcomes

- 7 Teaching Environment Modification Techniques

- 8 Developmental and Parent-Mediated Treatment Models

- 9 Outcome-Effectiveness for Developmental and Parent-Mediated Treatment Models

- 10 Sensory and Physical Stimulation Treatments

- 11 Eclectic Interventions

- 12 Inclusive or Special Education

- 13 Interventions – What is Known about What Works?

- References

- Index

- End User License Agreement