![]()

CHAPTER 1

Modifying Risk Factors to Improve Prognosis

Kevin S. Channer1 and Ever D. Grech2

1Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield, UK

2South Yorkshire Cardiothoracic Centre, Northern General Hospital, Sheffield, UK

OVERVIEW

- Certain personal characteristics and lifestyles point to increased likelihood of coronary heart disease and are called risk factors

- The three principal modifiable risk factors are smoking, hypercholesterolaemia and hypertension. Other modifiable factors linked to lifestyle include a saturated-fat-rich diet, obesity and physical inactivity

- Prevention strategies (primary or secondary prevention) aim to reduce the risk of developing or retard the progression of atheroma, to stabilise plaques and to reduce the risk of their erosion or rupture. These measures can collectively reduce the risk of future cardiovascular events (mortality, myocardial infarction and strokes) by as much as 75–80%

- Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) revascularisation is not a cure for coronary heart disease and they are predominantly carried out to improve symptoms. They may have little or no prognostic impact in chronic stable angina. However, CABG and PCI confer significant short- and long-term mortality benefit in acute coronary syndromes and, in particular, primary PCI for acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction

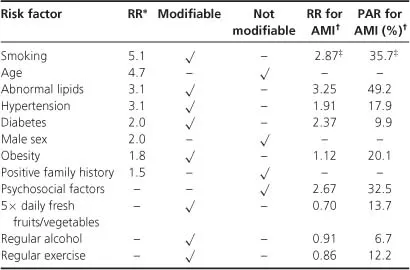

In affluent societies, coronary artery disease causes severe disability and more deaths than any other disease including cancer. It manifests itself as silent ischaemia, angina, unstable angina, myocardial infarction, arrhythmias, heart failure and sudden death. Although this is the result of atheromatous plaque formation and its effect, the actual cause of this process is not known. However, predictive variables – known as risk factors –have been identified which increase the chance of its early development. Risk factors can be classified as modifiable and non-modifiable (Table 1.1).

It is clearly not possible to prevent the increased risk associated with ageing, a positive family history or male gender. However, there are many factors which can be usefully ameliorated by interventions. Moreover, there are some aspects of lifestyle that have been shown to reduce the risk of an acute myocardial infarction.

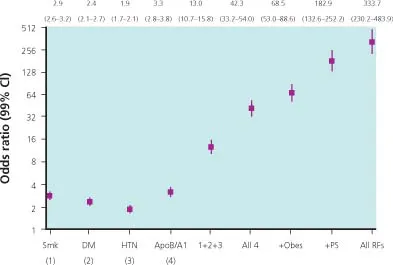

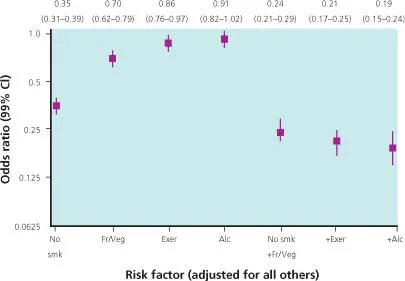

Risk factors are not simply additive but may be synergistically cumulative. Data from epidemiological surveys have shown for some time that combinations of risk factors generate exponential risks (Figures 1.1 and 1.2). This applies to both men and women. Risk factors are not static but increase with age – this may partly explain the independent effect of age. Blood pressure increases normally with age, so whatever definition is used for hypertension, the frequency of this condition will increase with age. Cholesterol and triglycerides increase with age as do insulin resistance and body mass index.

Impact of risk factors

Smoking

Smoking confers a fivefold relative risk for acute myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death. By comparison, stopping smoking has an almost immediate effect on reducing the cardiovascular risk by about 50%. Ex-smokers still have a higher risk than lifelong non-smokers. In one study, the survival rate of patients who stopped smoking after an acute myocardial infarction at 8 years of follow-up was about 75% compared with 60% for patients who continued to smoke. Similarly reinfarction is about twice as common in smokers than in those who stop smoking after a first infarction. At 8 years of follow-up, reinfarction was about 38% in smokers compared with 22% in quitters. Overall smoking increases mortality by about 2.5 times and reduces absolute survival by, on average, 10 years.

Hyperlipidaemia

High blood cholesterol is associated with an increased cardiovascular risk. However, as a single risk factor it is relatively weak – it becomes more important when associated with smoking, hypertension and diabetes. There is also an important interaction with age. In men, there is a doubling of risk from serum cholesterol in the lowest population quintile (<200 mg/dl; 5.2 mmol/l) to the highest (>260mg/dl; >6.7mmol/l).

Hypertension

Both diastolic and systolic hypertension have been shown to be risk factors for myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death. The relative risk of persistently elevated blood pressure of > 160 mmHg systolic is 4 times the risk compared with systolic blood pressure of < 120 mmHg.

The relative risk of persistently elevated diastolic blood pressure > 100 mmHg is 3 times higher when compared with a diastolic pressure of <80mmHg. Research data have shown that reduction in diastolic pressure of 5–6 mmHg and systolic pressure of 10–14 mmHg over 5 years with drug therapy does reduce cardiac mortality and non-fatal myocardial infarction in elderly people by about 20%, and in younger people by about 14%. Data from the longitudinal epidemiological study in Framingham showed that left ventricular hypertrophy diagnosed by echocardiography is associated with a twofold increased risk in death in women and a 1.5-fold increased risk in men over a 4-year period.

Diabetes mellitus

This is a major risk factor for premature vascular disease, stroke, myocardial infarction and death. Diabetes increases the risk of developing coronary heart disease by 1.5 times at age 40–49 and by 1.7 times at age 50–59 in men and by 3.7 times at age 40–49, and 2.4 times at age 50–59 in women. There are data that show that diabetic control is important for cardiovascular risk, with correlations between cardiovascular events, ischaemic heart disease and death rate and glycosylated haemoglobin. Much more effective risk reduction is associated with aggressive treatment of the commonly associated hypertension, lipid abnormalities and obesity in the diabetic patient.

Obesity

Obesity has been increasing in epidemic proportions and confers a prognostic disadvantage. Those with body mass index (weight/ht2) of 25–29 kg/m2 are considered to be overweight and those >32 are classified as obese. The latter have a twofold relative increase in mortality from all causes and a threefold increase in cardiovascular death. One study showed that a high body mass index was associated with an increase risk of death per se, especially when it was present in young people aged 30–44 years. More recent evidence suggests that waist circumference is an important independent risk factor as truncal or visceral obesity appears to be more atherogenic. An expanded waist circumference is a necessary criterion for the diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome, in addition to at least two of the other four criteria (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2 International Diabetes Federation definition of metabolic syndrome – focus on waist circumference.

| Abdominal obesity plus at least two of the following: | >94 cm male, >80 cm female |

| Elevated triglycerides | ≥1.7 mmol/l |

| Reduced HDL-cholesterol | <1.0 mmol/l male, 1.3 mmol/l female |

| Raised blood pressure | >130/80 mmHg |

| Raised fasting plasma glucose | ≥5.6 mmol/l |

Despite the presence of the obesity paradox – overweight and obese patients with established cardiovascular disease seem to have a more favourable prognosis than leaner patients – there is data to support purposeful weight reduction in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Furthermore, interventional trials involving bariatric surgery for severe obesity have shown that significant weight reduction resulted in significantly reduced mortality.

Physical activity and fitness

There is a close inverse relationship between cardiorespiratory fitness and cardiac outcomes such as coronary disease and death. This can be readily assessed by exercise tolerance testing. Patients with a low level of cardiorespiratory fitness have a 70% higher risk for all-cause mortality and a 56% higher risk for coronary or cardiovascular events compared with those with a high level of fitness. Those with intermediate levels of fitness have a 40% higher mortality risk and a 47% higher coronary or cardiovascular event rate than those with higher fitness. Following acute myocardial infarction or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), cardiac rehabilitation programmes that promote exercise and weight loss can improve cardiometabolic risk profiles of patients.

Gender

Men have twice the cardiovascular mortality as women at all ages and in all parts of the world. This was thought to be related to the beneficial effect of female sexhormones, especially oestrogens, as the cardiovascular risk in women increases after the menopause. However, two large randomised controlled trials showed that hormone replacement therapy (HRT) did not reduce the cardiovascular risk in women; rather, the thrombotic effects of oestrogens precipitated fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events, especially in the early years of treatment. Women appear to possess differently weighted risk factors than men for reasons that are unclear.

More recent data have shown strong associations of accelerated atherosclerosis with low levels of testosterone in men followed up for 4–8 years. Low testosterone level in men has been shown to be linked with increased mortality. Male HRT has not yet been shown to reduce cardiovascular risk, although results from animal studies are encouraging.

Psychosocial factors

Some psychosocial factors double the risk of developing cardiovascular disease. Social class has an important effect on mortality from heart disease with people in low-income groups havi...