![]()

1

End of the Oil Era

Cause for Concern

The year 1859 was a double milestone in world history. Charles Darwin published his Origin of Species, and across the Atlantic, in a 33-state America, Edwin Drake sank the first US oil well in Titusville, Pennsylvania. Darwin offered the concept of the extinction of entire species as the backdrop for a potentially finite “Human Era,” while Drake’s discovery ushered in the “Oil Era,” whose end, some speculate, is not very far off.1,2 Since that year, oil has become the foundation of individual empires and a source of wealth for nations endowed with abundant reserves. Measured in antiquated units of 42-gallon barrels, oil is both a practical commodity and a tradable international currency. Oil is used to produce a wide diversity of products, such as fuel, plastics, paint, nylon, cosmetics, toothbrushes, and toothpaste. Our freedom of movement depends on oil for gasoline, a liquid that propels, pollutes, and has typically cost less than most bottled water. Oil’s global abundance is ultimately unknown, yet the competition for control of this resource in the Middle East and fear about its future have been an impetus for war.3

That the world must run out of oil, perhaps some day soon, seems so obvious to most people that it is difficult to believe the topic is debated among scholars ranging from scientists to economists. After all, there is a finite amount of oil in Earth. That cannot be debated. Intuition tells us that scarcity is inevitable, given our societal history of consumption, our huge and continuing appetite for oil, and the fact that every developing nation relies on oil as a major stepping-stone to modernization. It stands to reason that global energy consumption must be increasing with our ever-growing population, particularly in the emerging mega-industrial regions of China and India.

Common wisdom holds that since oil is a finite resource, its supply must be rapidly diminishing in the presence of clearly increasing demand, and the end of our days of oil must be on the horizon. Yet there have been predictions of the end of oil since it first became a common commodity. As early as 1916, the US Bureau of Mines stated, “… with no assured source of domestic supply in sight, the United States is confronted with a national crisis of the first magnitude.”4 A report commissioned by the US Department of Energy, called the Hirsch Report (2005), begins with the ominous warning, “The peaking of world oil production presents the U.S. and the world with an unprecedented risk management problem. As peaking is approached, liquid fuel prices and price volatility will increase dramatically, and, without timely mitigation, the economic, social, and political costs will be unprecedented.”5 A piece published in the journal Science in 2007 states, “The world’s production of oil will peak, everyone agrees. Sometime in the coming decades, the amazing machinery of oil production that doubled world oil output every decade for a century will sputter. Output will stop rising, even as demand continues to grow. The question is when.”6 Similarly, a 2007 assessment by the US Government Accountability Office reported on the uncertainty of future global oil supply based on the premise that global oil production will peak and begin to decline “sometime between now and 2040,” with the majority of cited studies suggesting that the production peak will likely occur by 2020.7 Is this fear and doom-saying just another in a succession of false alarms?

Some experts say that there is plenty of oil. The essence of the idea that we will not run out any time soon was expressed in June of 2000 by former Saudi Oil Minister (1962–86) Sheikh Zaki Yamani. He claimed, “Thirty years from now there will be a huge amount of oil – and no buyers. Oil will be left in the ground. The Stone Age came to an end, not because we had a lack of stones, and the oil age will come to an end not because we have a lack of oil.”8 The Energy Information Administration (EIA), which is part of the US Department of Energy, says that only 4–7 percent of the world’s original in-place liquid petroleum has been recovered.9 Individuals ranging from oil company executives to energy consultants to academic economists firmly believe that any concerns about global depletion in the foreseeable future are premature for several reasons – oil is abundant, we have only consumed a fraction of the global oil endowment, technology to discover and extract new oil has consistently proven out, and the profit motive combined with the law of supply and demand will prevail.10 – 13

Why is our oil future so uncertain? What are the underlying data, analyses, and philosophies that lead to predictions of global oil depletion by some versus the conviction by others that the current state of alarm is unjustified and just crying wolf? Why is there any controversy at all? We can begin to answer these questions by considering the arguments supporting our intuition that the end of the Oil Era is near.

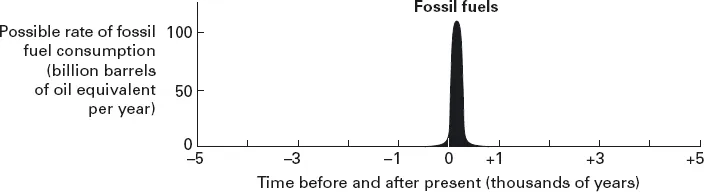

The Oil Era is a period of hundreds of years, contained in a longer period, during which global fossil fuel resources14 are being consumed (Figure 1.1). Fossil fuels are the remains of ancient plants and animals. They represent a history of stored energy from the sun, which directly or indirectly gave them life and substance. Although fossil fuels took millions of years to form, humans are consuming them, and oil in particular, over a very brief span of Earth history. On the scale of thousands of years, looking back and to the future, “The consumption of energy from fossil fuels is thus seen to be but a ‘pip,’ rising sharply from zero to a maximum, and almost as sharply declining, and thus representing but a moment in the total of human history.”15

Figure 1.1 The consumption of fossil fuels considered over a 10,000-year horizon. The resource will likely be used during a relative instant of Earth history (after Hubbert, 1956 and 1981).16

Based on the presumption that the depletion of the world’s oil resources is unavoidable, oil resource analysts have focused on four simple questions: How much oil exists to be exploited? What is the likely trend of new discoveries? What is the projected rate of global consumption? And, when will the end of the Oil Era arrive? Answering these questions is a subject of intense discussion in both the scientific literature and popular press. Many oil analysts have made estimates and projections. Cutting to the chase, most of these analysts have focused on the final question about when the end of oil will come, but they have framed the question in a slightly different way. The oil analysts focus not on when the last drop of oil will be pumped from the ground but rather the time when oil production will reach its peak (“peak oil”). It is their belief that the occurrence of peak oil production marks the beginning of the end, that is, the point when production can no longer keep up with demand. The argument goes that at the peak of oil production, the end is in sight, and it is urgent that a fundamental restructuring of our oilbased society begin.

So, when do analysts say that “peak oil” will occur? Surprisingly, the projections do not differ by much. The average collective estimate is that global peak oil production will occur before 2025, with the more pessimistic analysts suggesting that the peak has already occurred and we just do not know it, and the optimists pushing the date out to almost 2050. Remarkably, a great deal is made of the differences among the estimated times to peak oil production, and the debate among analysts is vigorous. But why is the exact year so important? The big message is that if they are correct, a key turning point in the nature of global industrial societies will occur within our likely lifetimes.

Hubbert’s Curve

The general agreement among so many oil analysts regarding the time to peak oil production is not a tremendous surprise, because most use the same basic method for prediction. Although there are different flavors of the approach, they are based on the original method proposed by M. King Hubbert (1903–89), who initiated the modern-day scientific debate about oil depletion. Hubbert was a Texas-born geologist, oil company research scientist, and energy resource analyst. A respected scientist with a PhD in geology from the University of Chicago, he made durable contributions to the fields of both petroleum exploration and the study of natural subsurface water flow. After a 20-year career at Shell Oil and Shell Development companies, Hubbert joined the US Geological Survey (USGS) in 1963 and began a five-year teaching position at Stanford University. In 1973 he was appointed California Regent’s professor at the University of California at Berkeley. Hubbert retired from academia in 1976, although he remained affiliated with the USGS.17 He published more than 70 articles, and his work is still highly regarded and commonly referenced. Hubbert was famous during his lifetime, being elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1955 and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1957. He was the president of the Geological Society of America in 1962 and was awarded the Rockefeller Public Service Award in 1977. Hubbert was not only appreciated in scientific circles for his scholarly publications but also enjoyed attention in the press when it came to energy resources. After making predictions of the likely near-term depletion of US oil and natural gas as well as global oil resources, and suggesting that the development of nuclear energy was the best course of action, he testified before Congress on the bleak future of fossil-fuel energy resources.

The main theme in many of Hubbert’s articles and monographs on energy resources was the fragility of our industrial global society that is so dependent on energy. He was fixated on the seemingly inevitable collision of finite Earth resources and the exploitation of those resources under the pressures of explosive global population growth. In a compelling 1949 article in the journal Science, Hubbert tied the consequences of exponential population growth to the general problem of fossil fuel depletion, considering oil, gas, and coal. Hubbert argued persuasively that even the habitable land required by society as we know it could not be sustained given a doubling of global population every hundred years, a 0.7 percent annual rate of increase that characterized population growth in the first half of the twentieth century. In his words,

Such a rate is not “normal” as can be seen by backward extrapolation. If it had prevailed throughout human history, beginning with the mythical Adam and Eve, only 3,300 years would have been required to reach the present population.

… In fact, at such a rate, only 1,600 years would be required to reach a population density of one person for each square meter of the land surface of the Earth.18

Throughout his career, Hubbert offered various forecasts of the decline in global oil supply, with published time-to-peak-oil predictions ranging from 1990 to 2000. His forecast peak dates were premature, but in the overall scheme of things, they do not differ dramatically from those made by modernday energy analysts. Toward the end of his active career, Hubbert repeated the same somber message that he had put forth during prior decades,

It is difficult for people living now who have become accustomed to the steady exponential growth in the consumption of energy from fossil fuels, to realize how transitory the fossil-fuel epoch will eventually prove to be when it is viewed over a longer span of human history.19

With his steadfast belief in exponentially increasing demand overtaking limited supply, Hubbert presented a quantitative method to represent the amount of any natural resource and its estimated rate of depletion. Hubbert’s curve, as it is known, is a graph that shows the extraction of petroleum, or any non-renewable Earth resource, versus time. It is a bell-shaped curve, called a logistic curve,20 similar in appearance to the bell-curve normal distribution commonly used in statistical analysis.

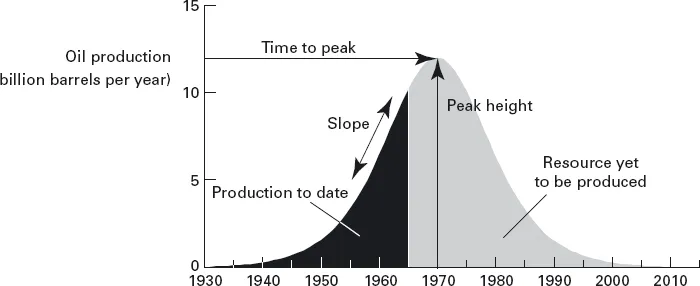

Hubbert used a straightforward formula that yields the curve as illustrated in Figure 1.2. The logistic-curve formula is a simple expression with three adjustable parameters (mathematical knobs) that control the slope, peak height, and time of the peak. The values of the parameters are adjusted to fit the historical production rates (data), which are matched by the curve since production began until production data are no longer available. With the constraint that the area under the curve represents the resource endowment, or total amount that can ultimately be produced plus the amount already produced, the formula is used to predict the future rate of resource production and depletion. The declining limb of the curve mirrors the rising limb. As Hubbert saw it, the use of any finite resource has a beginning, middle, and end. Indeed, it seems obvious that every finite commodity that is regularly consumed – from our life savings to our material supplies – must come to an end. Hubbert’s curve reflects that commonly held belief.

Figure 1.2 Generalized illustration of a logistic curve, showing its symmetric bell shape that Hubbert used to describe the rise, peak, and fall in production of a fossil fuel over time.

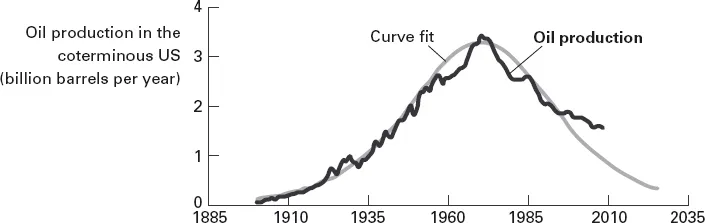

Hubbert’s approach was to take historical data of oil production over time and fit the logistic formula (his bell-shaped curve) to those data. The approach is attractive because anyone can reproduce it by fitting this or a similar bell curve to pre-peak production data. Hubbert observed that after oil was first extracted by wells in the 1860s, there was a rapid increase and then a marked decline in the discovery of new oil fields in the coterminous US, with the discovery peak occurring in the mid-1930s. He predicted that production would follow a similar decline. Figure 1.3 shows a logistic curve fit to historical oil production data through 2008 for US oil production in the lower 48 (coterminous) states, for which Hubbert estimated an oil endowment of 200 billion barrels.

The historical leg of the curve through 1956, when Hubbert made his original prediction, matches the oil production data. The early period of oil production and other resource utilization tends to display a rapid exponential increase. As time continued, oil production increased, but the rate of increase slowed until peak production (about 3.5 billion barrels per year for the lower 48 states) was reached. The date corresponding to this peak (actually occurring in 1970) is the time of maximum oil production, or “peak oil” production. Beyond peak oil, supplies presumably become depleted more rapidly than production from new discoveries can be brought on line. The curve after the peak falls back toward a level of nominal production. Eventually, the resource is exhausted when cumulative production nears the value of the oil endowment.

Figure 1.3 US lower 48 state oil production data and a curve fit using Hubbert’s approach based on an estimated oil endowment of 200 billion barrels. (Data: EIA)

One might wonder how robust the curve-fitting procedure might be. That is, perhaps it is possible to fit the historical data with a variety of curves, each showing a different time to peak oil. It turns out that, even though the shapes of various curves that fit these data might be a bit different, the time of peak oil estimated using the approach does not vary by much. This is because there are two primary constraints controlling the curve-fitting process. The first constraint is that the historical data, typically representing the period before the peak, must be fit by the rising production limb of the curve. Only a limited subset of curves can match those historical data because they show a particular trajectory of increasing oil production. The second constraint is...