![]()

Part 1

Ancient Asia

![]()

Chapter 1

Ancient West Asia

Exhausted, Ninhursag yearned for a beer.

The great gods languished where she sat weeping.

Like sheep they could only bleat their distress.

Thirsty they were, their lips rimed with hunger.

For seven whole days and seven whole nights

The torrent, the storm, the flood still raged on.

Then Atrahasis put down his great boat

And sacrificed oxen and many goats.

Smelling the fragrance of the offering

Like big flies, the gods kept buzzing about.

From the Sumerian story of the Flood

The First Civilisation: Sumer

Appreciation of Asia’s antiquity is recent. Apart from China, whose uniquely continuous civilisation preserved a record of its own ancient origin, the rest of the Asian continent had to wait for modern archaeology to reveal the cultural achievements of the earliest city dwellers. Excavations over the past century and a half have uncovered lost civilisations in West Asia as well as India. Near Mosul in northern Iraq, exploration of a mound at the site of ancient Nineveh resulted in the recovery of the library belonging to the Assyrian kings, a treasure trove for understanding the world’s first civilisation. Surviving texts provide a means of approaching the Sumerians, who founded their cities more than two thousand years before Nineveh fell in 612 BC to a combined attack of the Babylonians and the Iranian Medes. The destruction of this last Assyrian city ushered in the final era of ancient West Asian history, that of Persian power.

Because the royal library comprised a collection of Mesopotamian compositions going right back to Sumerian times, it is hardly surprising that their translation became a focus of keen interest. No one could have expected, however, the sensation caused in 1872 by the Babylonian story of the Flood, an event that appears first in Atrahasis, the name of the Noah-like hero of this oldest Sumerian epic. There is no mention of sinfulness as in the biblical account: instead, the gods inundated the Earth to stop the racket that people were making below the stairs. The sky god Enlil found sleep quite impossible, so plague, famine and flood were in turn employed to reduce the numbers then overcrowding the world. Warning of the final disaster was given to Atrahasis by Enki, the Sumerian water god.

Although in the 1920s discoveries of mounds in the Indus valley led to the excavation of two ruined cities at Mohenjo-daro in Sind and Harappa in western Punjab, and in the process redrew the world map of ancient civilisations, the finds had a less dramatic impact than the earlier Mesopotamian ones because of our inability to decipher the Indus script. Sumer and Babylon had long emerged in a civilised way of living at the time the inhabitants of the Indus valley built their remarkable cities. Only China was a late starter in Asia, the Indus civilisation having collapsed more than a century before its first historical dynasty, the Shang, arose about 1650 BC on the north China plain. In spite of the decipherment problem, the material remains of the Indus valley cities bear witness to an influence on the subcontinent’s chief concern, namely religion. Defeated though they were by the Aryan invaders, the Indus valley people were not without their revenge because their beliefs came to have a profound effect on the outlook of the Aryans. Besides absorbing the Indus preoccupation with ritual ablution, they became fascinated by the possibilities of yoga, whose austerities were supposed to empower the rishis, divinely inspired seers. That an Indus valley seal shows a horned god in a yoga posture may explain the rise of Shiva, “the divine rishi”, to a senior position in the Hindu pantheon, displacing warlike Indra. It had been Indra as Purandara, “the fort destroyer”, who gave the invading Aryans victory over the Indus valley settlements.

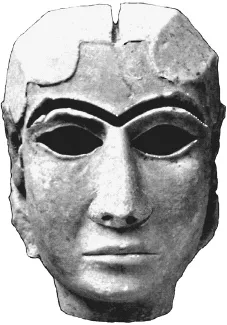

Nothing is known about the arrival of the Sumerians in southern Iraq. As they believed that they had travelled in a westerly direction, the discovery of the Indus civilisation has encouraged the idea of the Sumerians being earlier occupiers of northwestern India. But it is just as likely that they moved into the Tigris–Euphrates river valleys from Iran, as did other migrants attracted to their agricultural potential, although there is also the possibility that the Sumerians always lived in Iraq. The name by which they are called is Babylonian, which means the people who live in Sumer, southern Babylonia. They named their own country Kengir, “the civilised land”: it stretched from the sea to the city of Nippur, one hundred kilometres south of present-day Baghdad. A semi-arid climate ensured that irrigation was essential from the start, artificial canals eventually developing into an extensive network that required constant supervision, dredging and repair. As a result of this management of water resources, groups of villages came under the direction of larger settlements, the first cities ruled by princes or kings, who considered themselves to be representatives of the gods. The Sumerians seem only to have distinguished between city prince, ensi, and king, lugal, after 2650 BC, the approximate date for the establishment of the earliest known royal dynasty.

Fundamental to a Sumerian king’s power was a large retinue of unfree retainers, in part recruited from captives whose lives the king had spared. This military tradition lingered into the medieval period: the Janissaries of the Ottoman sultan Mehmet II, who captured Constantinople in 1453, were all ex-Christian slaves. These lifelong soldiers even formed the sultan’s personal bodyguard. Like the Janissaries, the Sumerian king owned his retainers body and soul: they ate with him in the palace and did his bidding in war as well as peace. In addition to this power base, rulers sought to broaden their support by making their authority available to the underprivileged in Sumerian society: they presided over a legal system designed to protect the least well-off from the rich and powerful.

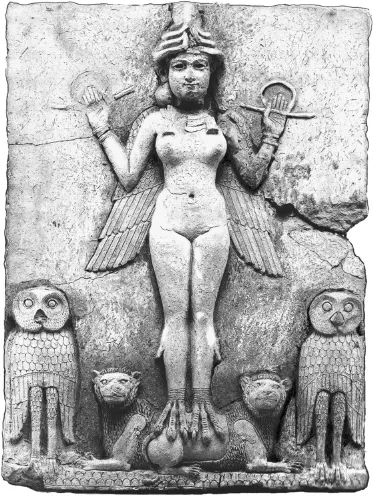

Because cities expanded around temples, the nuclei of all significant foundations, the Sumerians looked to the resident deities for prosperity. In the southernmost cities, situated close to the marshlands, the city gods were connected with fishing and fowling; upriver divine influence was spread over fields and orchards, the date growers paying special attention to the prodigious powers of Inanna, goddess of fertility; in the grasslands, worship was given over to Dumuzi, the holy shepherd. Because she combined in her person several originally distinct goddesses, Inanna was the most important goddess in the Sumerian pantheon, a variant of her name being Ninanna, “mistress of heaven”. Identified with the planet Venus as the morning and the evening star, Inanna was the bitter enemy of her sister goddess Ereshkigal, “the mistress of death”, and once she had the temerity to visit the “land of no return” so as to assert her own authority there. At each of its seven portals, she was obliged to take off a garment or ornament, until at last she stood naked before Ereshkigal. After hanging on a stake for three days, the water god Enki sent two sexless beings to revive Inanna’s corpse with the “food and water of life”.

But after her escape from death, the goddess could not shake off a ghastly escort of demons who followed her as she wandered from city to city. They refused to depart unless a substitute was found. So Inanna returned home to Uruk, took offence in finding her husband Dumuzi at a feast, and let the demons carry him off to Ereshkigal’s underworld. Thereafter Dumuzi’s fate was spending half the year in the land of the living, the other half with the dead. Thus he became West Asia’s original dying-and-rising god.

At Uruk there is compelling evidence that the king acted as an intermediary between the city and the city goddess through the New Year rite of a sacred marriage. The ruler impersonated Dumuzi, a high priestess Inanna. One text has the king of Uruk boast how he

lay on the splendid bed of Inanna, strewn with pure plants . . .

The day did not dawn, the night did not pass. For fifteen hours

I lay with Inanna.

Capable of making endless love, the goddess was the awakening force that stirs desire in people and causes ripeness in vegetation. A ruler’s enjoyment of “the sweetness of her holy loins” was regarded by the Sumerians as vitally important because this sacred coupling guaranteed a city’s survival. It is tempting to see their joy during the festival as recognition that a new seasonal cycle was about to begin, marked by the return of Dumuzi from the underworld to Inanna’s “ever youthful bed”. In the Song of Solomon we find an unexpected parallel of such sensuousness, when “until the break of day, and the shadows fell away”, the lover is exhorted to act “like a roe and a young hart on the mountains of Bether”. This short love poem may well echo the rite of sacred marriage, even though an alternative view looks to Egypt for the source of inspiration. The authorship and the date of composition, not to say the inclusion of the Song of Solomon in the Bible, remain an unsolved mystery.

Uruk is also the setting of the Babylonian epic about Gilgamesh, a legendary Sumerian king whose original name was Bilgames. The city’s earliest rulers fascinated later poets, much as the heroes of the Trojan War did the Greek epic poet Homer. They were the favourite subjects of court entertainment, their adventures being retold to ruler after ruler. Though it was the writing school of King Shulgi at Ur that set down for posterity the literary tradition of Sumer just before the close of the third millennium BC, the fullest surviving text of Gilgamesh’s exploits comes from the Assyrian royal library at Nineveh. Translation of a small section of the epic was responsible for the furore in 1872, because it relates the visit made by Gilgamesh to his ancestor Utanapishtim, the one chosen to escape the Flood that “returned all mankind to clay”. A later version of the Sumerian hero Atrahasis, this venerable sage was prepared to impart truth only to the man who dared to find him and was capable of doing so. The reason for Gilgamesh’s visit to Utanapishtim was the grief that had overwhelmed him on the death of his companion Enkidu, something the distraught hero refused to accept as the inevitable end to life. Gilgamesh “wept over the corpse for seven days and seven nights, refusing to give it up for burial until a maggot fell from one of the nostrils”.

Reaching Utanapishtim’s subterranean house, Gilgamesh learns that his quest is hopeless, when Utanapishtim tells him he cannot resist sleep, let alone death. The only chance is a fantastic plant named “Never Grow Old” at the bottom of the sea. At great risk Gilgamesh fetches it from the deep and happily turns his steps to Uruk, but on his way home, while he dozes by a waterhole, a serpent smells the wonderful perfume of the leaves, and swallows the lot. Immediately the snake was able to slough its skin, and Gilgamesh realised that there was no way that he could avoid the underworld, “the house of dust”.

Our knowledge of the Sumerians derives from their invention of writing, quite possibly the most consequential advance in all human history. This stroke of genius not only gave support to an expanding economy, through easing communication within crowded cities, but it also permitted the formation of reliable archives. Obviously the use of script, as a substitute for verbal agreements, was of immediate value in commercial transactions, the importance of which can be gauged from the protection afforded to trade routes by successive kings. Even more valuable for a record of the very first civilisation on the planet was the ability to set down in a permanent medium the ideas that informed its workings. Without the Sumerian script we would neither possess poetical works such as the Gilgamesh epic, nor appreciate how deep was the Sumerian preoccupation with death. About 3000 BC, the Sumerians in Uruk hit upon the notion of creating hundreds of pictograms, plus signs for numbers and measures: these were pressed into clay tablets with a reed stylus to compose what is called the cuneiform system of writing.

The idea that it was possible to capture a language by means of writing travelled along the ancient trade routes. In Babylon the adoption of cuneiform for Akkadian, a Semitic tongue, meant that long after Sumerian became a dead language the educated remained familiar with it—just as Latin was prized in Europe until the Renaissance. The first Semites must have entered northern Babylonia not much later than the Sumerians, whom they eventually submerged through further waves of migration. Elam was the first state in Iran to follow Babylon’s example and, given established trade links between Mesopotamia and India via the island of Bahrain, stimulus for the Indus script could well have derived from merchant enterprise as well. Those who suggest that the idea of writing spread beyond India to China are wrong, however. Finds at Banpo, a fortified village close to modern Xi’an, in Shaanxi province, indicate how about the same time that the Sumerians began writing on clay tablets, its inhabitants incised their pottery with the antecedents of Chinese characters. Although fully developed words are not in evidence until the Shang kings recorded queries to their exulted ancestors on oracle bones, the extreme antiquity of the Banpo signs argues against diffusion.

The unification of Sumer curtailed inter-city conflicts once disputes came to be settled by royal adjudication. This wider system of government formed the context of Uruinimgina’s laws, which stand at the head of a long series including Hammurabi’s famous code. King Uruinimgina of Lagash deplored his predecessors’ confiscation of temple properties, which he returned. Driven from Lagash, he continued to rule as king at Girsu before being taken prisoner by the Semitic ruler of Akkad, where he died in 2340 BC. Even though the location of Akkad remains unknown, this ancient city was situated somewhere in northern Babylonia. For the Sumerians its rise as an imperial power spelt the beginning of the end of their independence. Yet Akkad’s favourite instrument of power, wholesale massacre, could not ultimately ensure the survival of an empire that included Mesopotamia and Syria as well as eastern Asia Minor. Its nemesis were the semi-nomadic Gutians, who descended from the mountains of Iran and terrorised Semites and Sumerians alike.

After the collapse of Akkad, there occurred a last flourishing of Sumerian culture, which was recorded by King Shulgi’s scribes. His capital at Ur escaped the violent attentions of new raiders from Iran through the construction shortly before 2050 BC of “a wall in front of the mountains”. But his successors were less fortunate when the Elamites, supported by their Iranian allies, launched a devastating attack on Sumer. A lament tells us how “water no longer flows in weed-free canals, the hoe does not tend fertile fields, no seed is planted in the ground, on the plain the oxherd’s song goes unheard, and in the cattle pen there is never the sound of churning”. The gods have gone, their temples defiled, and ancient ways “are changed forever”. Not even the dogs of Ur remained in the ruined city.

The Great Empires: Babylon, Assyria and Persia

Archaeological recovery of Babylon’s past followed in the wake of the discoveries in ancient Assyria. Despite being less spectacular than those of Nineveh, the excavation of northern Babylonia led to a realisation that here was another early Asian civilisation of great sophistication. How else could Babylon have once been renowned for its Hanging Gardens? Together with the city’s walls, they were regarded as one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

Babylon was founded shortly after the Elamite devastation of Sumer. During these troubled times its inhabitants had the benefit of a poli...