![]()

Part 1

PLAYIN’

AND

FIGHTIN’

![]()

1

VIOLENCE AS “THE RECESS PROBLEM”

Mr. Rumble, an energetic, middle-aged white man, wore professional clothes and sparkled with the energy of someone who was confident in his role as principal. He welcomed me as a fellow professional and became nostalgic for his graduate school days. A man in transition, he allowed me complete access to the school for research purposes. I observed not only the school yard but the cafeteria, the gym, the evening holiday performances, and the third-, fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-grade classrooms, and hung out in the teachers’ lounge. Eventually I was allowed to videotape—with parental permission—from the school’s second-floor window and on the playground itself.

As part of my agreement with Mr. Rumble, I was asked to find patterns of aggression in the school yard as I recorded the children’s folk games. This agreement rationalized my constant presence, given the ever-present concerns regarding “school yard violence” and “the recess problem.” Because educators assumed that recess was violent, playtime had been canceled, reintroduced, canceled again, turned into gym, made into a formalized program, and then reinstituted as a consequence of teachers’ union demands. Years after the first cancellation, teachers at the school still spoke of “the recess problem,” and I set out to find out what that problem was.

In the teachers’ lounge and in university libraries, the playground has typically been associated with violence, chaos, and bullying rather than what I saw: friendship, skill, challenge, and the negotiation of culture. The grown-ups of the Mill School consistently used chaotic, wild, and unruly to describe school yard happenings. Their eyes saw the zigzagging runners and the children who refused to cooperate to line up and were surprised that the children actually played as many games as they did.

The staff grimaced at games with names that invoked mock violence (Suicide Handball and the Fighting Game) yet were nostalgic about their own childhood games, which they remembered with difficulty (Red Rover, tag, dodgeball). Educators used the violent game titles to rationalize militancy and told stories of children needing to be taken to the nurse after recess play. Given the Mill School’s mix of pretend violent drama and real aggression, distinctions used by animal ethologists to study play fighting in the wild offer the most useful place to start.

Gregory Bateson, ever watchful of animal play, notes that play fighting is very much like the real thing but is not the real thing exactly.1 Play fighting and real aggression are communicatively different, signaling different kinds of relationships, even though the mock and the real fighting can slip from one to another in an instant. In play fighting, the children, like animals, generally remain together after the episode is over. In moments of real fighting, the individuals separate.2 The quality of the activity is signaled by this extension of continued relationship or the breaking up of the interaction.

Anthony Pellegrini’s work on rough-and-tumble play has raised some important questions regarding the exact descriptions of this type of activity, highlighting adult misperceptions about what is destructive and what is merely playful.3 But the literature on play fighting has virtually ignored children’s control or lack of control in the creation of violent moments. I decided to have the children give advice about “the recess problem” and to comb through the video ethnographic data to look for patterns. Where and when were children getting hurt in the school yard? Is the removal of their playtime justified, or is it, as sociologist Pierre Bourdieu would suggest, a “useful fiction”?4

In their interviews, the children gave clues to the key moments to be studied. They repeatedly mentioned the difficulty of ending recess and how children were often hurt while lining up. One boy who spoke little during our discussions said that “going in was the worst part of school.” It was the pointer I was looking for.

When the bell rings, we like—

When the bell rings—

We try to stay there—

I know!

When the bell rings, and when our teacher [speaking urgently into the microphone]—

When the bell rings and when our teacher, and when they don’t come, and when they don’t come out early—

Yeah.

We start playing rope again!

And when the bell rings I like to pick on—I like to hit the boys [excited chatter].

We like to hit them upside the head, and then they’re always chasing after us, but we run.

Some people go and line up—some people go and line up and fight in line.

Some people run around in the back of the line.

People pull hair.

Yeah.

And let their hair get all messed up.

They do steps in back of the line.

And because they just pulled their hair or something like that.

Yeah, like my hair—see how it’s all messed up?

And they clown around or something.

They don’t like them, they start fighting.

The clues were: “When the bell rings”; “I like to hit the boys, go in line … and fight in line”; “Going in is the worst part of school.” I asked in small-group interviews about what happens when the bell rings.

We get mad.

(You get mad?)

Sometimes Ms. Gee keeps us for recess, and that’s not fair.

But a lot of times they be cuttin’ us out, they be cuttin’ us out on the bell, because sometimes they just be like, 10:20 and they ring the bell.

In addition to the games, I filmed the lining-up procedure and the school yard in its entirety in wide angle. I then coded all incidents of violence, no matter how trivial, as either mock violence, where the players stayed together, or serious aggression, where the players separated. An interesting pattern emerged.

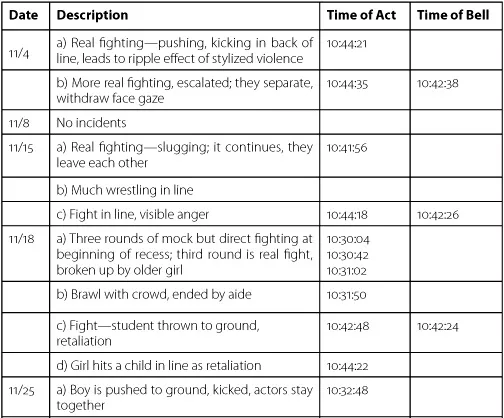

WIDE-ANGLE FOOTAGE

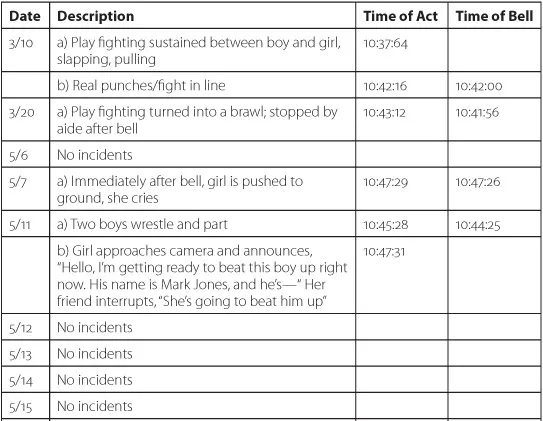

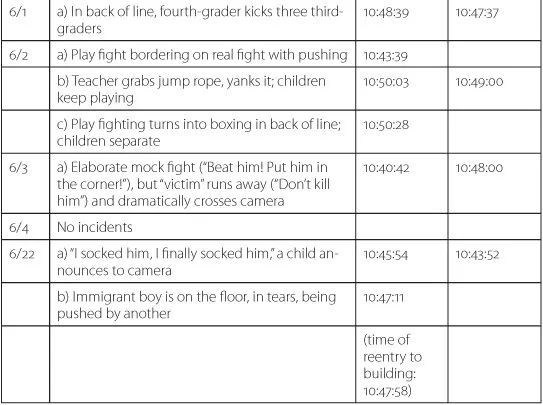

In the wide-angle footage, I looked for violence and noted its type and timing. Because I used two different cameras, some times are listed by hour:minute:seconds (e.g., 10:44:21), while some are listed according to minutes and seconds by a counter (25:34). The relation of the timing of the action to the sound of the bell, not the absolute time, is what is significant.

The hour:minute:second footage was taken from a second-floor window and was focused on the interaction while students were in line. Although the minute:second footage lacked this focus, the tapes of recess in June had a line closer to the building than the early fall footage taken with the same camera. As a result, a general wider angle was able to capture basic gestures and facial features, which are necessary for this type of coding.5 This analysis includes all relevant footage taken that was in focus during the 1991–92 school year. To have two cameras going simultaneously, one at the window, and one in the school yard, I worked with a trusty assistant.

Eight of these nine days showed distinct violence in the lining-up procedure, with six of the incidents occurring less than one minute from the ringing of the bell and the other two occurring within two minutes of the bell. Only two instances visible in all the wide-angle footage occurred at a time other than at the transition period. Some of the conflict that was not related to lining up occurred right at the beginning of recess, during another transition.

Anthropologists, psychologists, and sociologists have long written about transition times and spaces as wrought with danger and the possibility of creativity.6 Rites of passage focus on transitions in time; amulets and decorations guard transitional windows and doors in many traditional cultures. Tollbooths are known as zones of accidents, and many an argument occurs in the last few minutes of a visit with a friend or loved one. This phenomenon also appears in the school yard.

The ripple effect is visible in several of the tapes; pushing in line leads to retaliation, sometimes from bystanders, who then bump into other students. The sudden cessation of official games, the children’s close proximity and high excitement levels, and a long period of waiting to go inside clearly set the stage for violent interaction.7

In these cases of real fighting, the children do not have to physically separate because they are technically not allowed to do so, and attempting to get away from each other would be to lose face in a potentially humiliating public arena. Instead, we must look for the removal of the gaze, reorientation of the body, and visible signs of anger, including the intensity and speed of the physical response. In line, the children seem to have more difficulty reading each other’s clues—on two occasions, the two play fighters were joined in earnest by an outsider who then received serious retaliation from the initial play fighters.

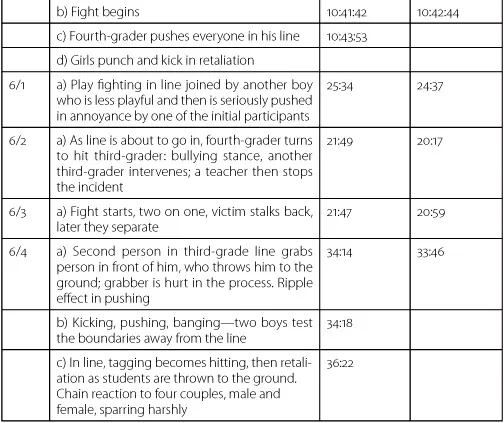

ZOOM FOOTAGE

In these episodes, the camera was often focusing on a game and fighting emerged in or around the play activity. Again, note the timing of the bell.

In all but one of the zoom images, the fighting occurs within a minute and a half of the ringing of the bell. Violence is clearly part of the transition time and is otherwise rarely visible in the play period. The problem was not play itself but the in-between state between playtime and class time.

Some of the examples occurred within seconds of the bell. The violent talk had a wider window of about two or three minutes, but the violent aftershock of the bell was clearly visible even with this initial small sample. In these examples, only one serious play fight took place outside of the transition period. The last example shows a gap of more than three minutes, but although a long time had passed since the bell rang, the violence occurred only forty-seven seconds before the students walked back into the building. The transition may have two parts, given the children’s extended waiting period.

Ironically, the teachers greet their students only during the transition period. When the teachers arrive, they witness the worst part of the students’ behavior, and like the story of the blind men and the elephant, they assume the tail is equal to the whole thing. The nonteaching aides who see the entire experience range from good-natured to policing and aggressive, waiting for the few children to “act out” and “mess up,” pink slips at the ready.

During the transition, attempts at authoritarian control worked only temporarily. A day after a severe talk by the principal was no different than the day before, even though the children considered him...