![]()

PART I

THE VOICE OF THE DOOR-KEEPER

He came to the prison. A bell-chain hung by the doorway and he pulled it. A panel in the door slid back.

“Monsieur,” said the man, removing his cap, “will you be so kind as to let me in and give me lodging for the night?”

“This is a prison, not an inn,” said the voice of the door-keeper. “If you want to be let in you must get yourself arrested.”

—Victor Hugo, Les Miserables

![]()

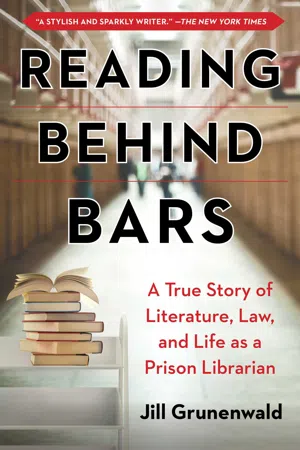

Chapter 1

Out of the Frying Pan

It is the policy of the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction (DRC) to ensure a background investigation is conducted on each state employee, intern, contractor, and volunteer under primary consideration for employment or entrance into any of its offices/institutions unless otherwise exempted by this policy. The purpose of the background investigation is to identify offenses or behaviors that may impact job performance, volunteer participation, or internship work, or their ability to provide services.

—ODRC Policy 34-PRO-07

The small, dusty village of Grafton, Ohio (population 6,636) is located on the far western outskirts of Cleveland. So far west that it isn’t really fair to even use Cleveland as a geographical reference point; but as a recent transplant in the opening act of 2009, that’s all I had. Although transplant isn’t the right term, either. “Prodigal Daughter” might be more appropriate. After high school, I—like LeBron James—had fled the quaint comfort of my Northeast Ohio hometown in an effort to find greener pastures, only to return after realizing Dorothy was right: there’s no place like home. (Granted, LeBron left again, but he brought us home a championship title. Between stints in Miami and Los Angeles, I can’t really blame the guy for escaping Cleveland winters.)

I had grown up not in the city of Cleveland but in the suburbs surrounding the city. Even then, Hudson was on the southeast side and I was far more familiar with the communities on the east side of the city than the west, where Grafton is located. Grafton was so far west from all familiar terrain it might as well have been in California.

As a town, Grafton offers its residents one industry of employment: corrections. It isn’t a flashy field and it definitely isn’t for everyone, but after the steel mills of nearby Youngstown had shuttered their doors, and the automobile industry was falling off the rails in Detroit, and the rest of the Rust Belt was struggling to survive, the prisons of Grafton could provide one thing very few employers could in the wake of the Great Recession: job security. Unless there was a major overhaul to our criminal justice system, prisons and the inmates housed in them weren’t going anywhere anytime soon.

Over the past two weeks, since accepting the position of librarian at the minimum-security prison, I had gone through a barrage of tests that evaluated my ability to perform critical job functions as well as my ability to maintain the safety and security of the facility. Simple enough, right?

Not so much. I started with the drug test. This was immediately complicated by the fact that I can’t pee on command. Ever. Whenever I have had to have x-rays taken (which, in my case, is about once every five years due a variety of very ungraceful moves that have resulted in multiple sprained ankles and broken bones), I’m that physically stubborn patient who, even after drinking water and/or purposely not using the restroom prior to the appointment, is encouraged to “just try” by the nurses even though I know I’m not pregnant. (How do I know you ask? Oh just little things called science! and cycles! and math! and just plain ol’ abstinence!) Then, I always sit in the sad, sterile bathroom with its harsh yellow light and white walls unable to “perform.” It often gets to the point where I just hand the nurse the empty cup and say I’ll sign whatever they need me to sign in order to absolve them of all fault if I somehow magically am pregnant.

But prison pee tests can’t be waived away with a signature and a “cross my heart, hope to die doc” because prison pee tests are looking for drugs. Nevermind that in my case this was an utterly pointless test as I am the least likely person I know to do drugs. I came of age during the “Just Say No” era, sitting through countless Drug Abuse Resistance Education (aka D.A.R.E.) programs throughout my childhood, while also witnessing Nancy Reagan on television warning of the dangers of drugs. I bought that party line and made it through high school, college, and even graduate school without ever once saying yes.

Of course, I had no way of convincing the lab assistant that I was drug free without filling the little plastic and very much empty cup in my hand. So I got prepared. While the lab shut down for an hour for lunch, I went to Walmart and bought the biggest bottle of water I could find. After chugging it down, I returned to the lab post-lunch and thankfully managed to produce the desired, if diluted, drug-free result. Check that one off the pre-employment checklist.

After the bladder blunder came a very extensive background check. I’d had background checks before but none of them involved driving out to the Lorain County Sheriff’s Office to be fingerprinted. My unique swirls and whirls were sent not just through the county and state system but the FBI database as well. I wasn’t very concerned about the background check (although suddenly every single unpaid parking ticket from my undergraduate years started to haunt me) but if nothing else, I knew that if I did pass this I’d never have to worry about another employment background check ever again. Seriously, nothing was going to top this.

Then there was the tuberculosis test. Or, as someone who grew up reading her fair share of tragic young adult novels set during the Victorian age, the consumption test. (This prompted much daydreaming: I was the anguished Fantine, desolate and destitute and dying without knowing the fate of my daughter Cosette. Or lovely little Helen Burns, leaving this world happy for the friendship of Jane Eyre.)

My knowledge of tuberculosis was so wrapped up in the fictional world I didn’t even know tuberculosis was even a thing that people could still catch, let alone that Cleveland’s MetroHealth hospital had an entire clinic dedicated to it that served all of Cuyahoga County.

Know what’s not a good thing to give to someone who’s mild OCD presents itself in the form of checking, checking, and rechecking things? A medical test that leaves a small bubble on the skin that needs to be examined two days later by a medical professional to see if it has changed. After getting injected I spent the next forty-eight hours checking the injection site with alarming frequency, my imagination crafting images of me coughing into lace, monogrammed handkerchiefs and producing spots of blood. (I also have a flair for the dramatic.) Spoiler alert: everything turned out fine.

The pre-employment process was long and arduous but I came out in one piece. Even the small bubble on my arm disappeared eventually. After also sitting through the required unarmed self-defense course, I now had permission to walk freely around the prison and fulfill the duties of a librarian. There was nothing to stop me now.

A few days later I was headed back to the prison, which stood on a long stretch of road flanked by its peer institutions. A month prior, when I made my first interview trip, Meredith Highland, head of HR, instructed me to look “for the one in the middle.” Soon enough I would learn the layout of the four facilities that make up Prison Row in Grafton, Ohio.

State Route 83 is an almost entirely vertical fifty-mile stretch that begins in Avon Lake, Ohio, a small city lapping the shores of Lake Erie to the north, then cuts right through the heart of Grafton as it makes its way south to Wooster, Ohio. Wooster isn’t exactly central Ohio, but it isn’t too far from it either.

The Grafton section of the highway is nestled in a very rural area. On the east side of the road, standing alone, was Lorain Correctional Institution. In addition to being a multiple-level security prison, Lorain also acted as one of the state’s two reception and distribution facilities for men. This essentially means that when an inmate who lives in the northern half of the state is sentenced, he is first sent to Lorain for processing and evaluation before making his way to his permanent prison. For the southern half of the state, there is a similar facility in Orient, Ohio. These intake centers only process male inmates: like most states, Ohio has gender-segregated prisons. Women, no matter the severity of their crime or sentence, are incarcerated at the Ohio Reformatory for Women, located in the center of the state near the capitol, Columbus.

Across the street from Lorain Correctional Institution are three other facilities. To the far left is Grafton Correctional Institution, a minimum-security prison similar in size to Lorain. On the far right was the Farm.

At nearly 1,200 acres, the Grafton Prison Farm functioned as both a prison and a working farm. While they were eventually all shut down in 2016, back in 2009 Ohio had ten prison farms, which historically offered inmates an opportunity to learn a skill they could take with them when they are released; another added benefit was that the farms also provided food for the prison. When it first opened, Grafton Prison Farm also operated as an honor farm: a facility that kept inmates there on their honor. This worked exactly as it sounds and worked about as well as you’d think, which is why, when I started working next door, it was no longer an honor farm but, instead, had a razor-wire fence that matched those of its neighbors.

Sandwiched between Grafton and the Farm, as promised, was my new employer.

Staring at my new work site, I felt like a fish out of water. I had neither intended nor set out to become a prison librarian. As a subject matter, prison libraries aren’t exactly standard material covered in a graduate school curriculum (or at least it wasn’t at mine) so I didn’t know they were even a thing and I certainly didn’t know what the term “correctional” meant within the context of a job ad found on a random website. Compound this with fact that I had an acquaintance who worked at a facility with the same name, only instead of “treatment facility” it was called “behavioral facility” and I conflated the two. It wasn’t until Highland called to set up an interview that the other shoe dropped.

The day of my interview I almost flaked. I wanted to flake but desperate times called for desperate measures and, if nothing else I figured it would be good interview practice for all of those other job interviews I would hopefully have. Job interviews that wouldn’t involve voluntarily stepping behind bars. But when Highland called me back with a job offer that included paid time off and benefits, well, I couldn’t really say no.

I steered my car into the parking lot and pulled into an open space, opting to park beneath a tall light pole, a habit I had developed in graduate school when I had late night classes that required walking across campus in the dark. Gathering my personal items, I took my cell out of my purse and flipped it open to check for any messages. My friends and family knew I was starting today and a few had sent along well wishes. Closing the phone, I returned it to the glove box. Cell phones were considered contraband and not allowed inside.

A black SUV, helmed by Corrections Officer Lewis, was slowly patrolling the perimeter of the parking lot as I pulled in. Along with cell phones, guns were also not allowed inside the prison. Lewis, and the other COs assigned perimeter duty, were the only corrections officers who were armed. An inmate couldn’t get shot while inside, but once he made it past that fence all bets were off. I had met Lewis a few days before at the unarmed self-defense course and as I got out of my car, she waved at me from across the parking lot. I returned her wave, took a deep breath, and headed up the long sidewalk to the main glass doors.

The lobby was quiet and empty. Nearly everything in the room was beige. Beige walls. Beige doors. Beige counters. The only things not beige were the brown lockers at the back of the room and several rows of brown chairs in the middle of the space, both reserved for visitors on visitation days. The chairs were worn from years of use, the faux leather cracked and split at the seams. Tufts of white stuffing poked out from the gaps.

A corrections officer, uniformed in the standard black, stood at the front of the room, and a metal detector separated us. He was the only other person in the lobby and his eyes followed me as I made my way to a tinted window in the far-right corner. Behind the window, shaded from my view, were the correctional officers working the security control room. They were the eyes and ears of the prison, safe, secure, and seemingly all-powerful behind reinforced steel walls.

“I’m the new librarian,” I spoke a little too loudly into the call box. “It’s my first day.” Taking a step back, I cleared my throat, wondering if they could tell how nervous and out of place I felt.

At waist level, a metal box opened and a drawer slid out. “Identification, please,” came a voice on the other side of the window. Squinting, I tried to make out any human shape behind the shaded glass, but the window was too dark to see anything. It felt almost like being in a noir novel. I was the plucky Girl Friday who had wandered into the villain’s secret speakeasy and I needed the secret password to get inside.

I fished my driver’s license out of my purse and dropped it in. The drawer disappeared until it was flush with the wall. I was allowed to proceed.

My shoes click-clacked against the also-beige tiles as I headed over to the officer. He waited patiently behind the counter as I piled my purse and lunch bag onto the end of the counter. On top of those items went my coat, incredibly heavy but very much required for Ohio winters.

I eyed the officer’s ID badge. Ever the diligent student, I was determined to learn the names of all of my new coworkers as quickly as possible. Schroeder, got it. Behind him was a floor to ceiling, wall-to-wall window that looked out over the prison. To the left was a nondescript long concrete building and a large green yard. In the far distance I could see the three housing units that the prison’s seven hundred inmates called home.

“First day,...