Cape Cod

Henry David Thoreau

Contents:

Henry David Thoreau – A Biographical Primer

Cape Cod

Introduction

I - The Shipwreck

Ii - Stage Coach Views

Iii - The Plains Of Nauset

Iv - The Beach

V - The Wellfleet Oysterman

Vi - The Beach Again

Vii - Across The Cape

Viii - The Highland Light

Ix - The Sea And The Desert

X - Provincetown

Cape Cod, H. D. Thoreau

Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck

86450 Altenmünster, Loschberg 9

Germany

ISBN: 9783849644772

www.jazzybee-verlag.de

www.facebook.com/jazzybeeverlag

Henry David Thoreau – A Biographical Primer

1817-1862 - American recluse, naturalist and writer, was born at Concord, Massachusetts, on the 12th of July 1817. To Thoreau this Concord country contained all of beauty and even grandeur that was necessary to the worshipper of nature: he once journeyed to Canada; he went west on one occasion; he sailed and explored a few rivers; for the rest, he haunted Concord and its neighbourhood as faithfully as the stork does its ancestral nest. John Thoreau, his father, who married the daughter of a New England clergyman, was the son of a John Thoreau of the isle of Jersey, who, in Boston, married a Scottish lady of the name of Burns. This last-named John was the son of Philippe Thoreau and his wife Marie le Gallais, persons of pure French blood, settled at St Helier, in Jersey. From his New England Puritan mother, from his Scottish grandmother, from his Jersey-American grandfather and from his remoter French ancestry Thoreau inherited distinctive traits: the Saxon element perhaps predominated, but the “hauntings of Celtism” were prevalent and potent. The stock of the Thoreaus was a robust one; and in Concord the family, though never wealthy nor officially influential, was ever held in peculiar respect. As a boy, Henry drove his mother's cow to the pastures, and thus early became enamoured of certain aspects of nature and of certain delights of solitude. At school and at Harvard University he in nowise distinguished himself, though he was an intelligently receptive student; he became, however, proficient enough in Greek, Latin, and the more general acquirements to enable him to act for a time as a master. But long before this he had become apprenticed to the learning of nature in preference to that of man: when only twelve years of age he had made collections for Agassiz, who had then just arrived in America, and already the meadows and the hedges and the stream-sides had become cabinets of rare knowledge to him. On the desertion of schoolmastering as a profession, Thoreau became a lecturer and author, though it was the labour of his hands which mainly supported him through many years of his life: professionally he was a surveyor. In the effort to reduce the practice of economy to a fine art he arrived at the conviction that the less labour a man did, over and above the positive demands of necessity, the better for him and for the community at large; he would have had the order of the week reversed — six days of rest for one of labour. It was in 1845 he made the now famous experiment of Walden. Desirous of proving to himself and others that man could be as independent of this kind as the nest-building bird, Thoreau retired to a hut of bis own construction on the pine-slope over against the shores of Walden Pond — a hut which he built, furnished and kept in order entirely by the labour of his own hands. During the two years of his residence in Walden woods he lived by the exercise of a little surveying, a little job-work and the tillage of a few acres of ground which produced him his beans and potatoes. His absolute independence was as little gained as if he had camped out in Hyde Park; relatively he lived the life of a recluse. He read considerably, wrote abundantly, thought actively if not widely, and came to know beasts, birds and fishes with an intimacy more extraordinary than was the case with St Francis of Assisi. Birds came at his call, and forgot their hereditary fear of man; beasts lipped and caressed him; the very fish in lake and stream would glide, unfearful, between his hands. This exquisite familiarity with bird and beast would make us love the memory of Thoreau if his egotism were triply as arrogant, if his often meaningless paradoxes were even more absurd, if his sympathies were even less humanitarian than we know them to have been. His Walden, the record of this fascinating two years' experience, must always remain a production of great interest and considerable psychological value. Some years before Thoreau took to Walden woods he made the chief friendship of his life, that with Emerson. He became one of the famous circle of the transcendentalists, always keenly preserving his own individuality amongst such more or less potent natures as Emerson, Hawthorne and Margaret Fuller. From Emerson he gained more than from any man, alive or dead; and, though the older philosopher both enjoyed and learned from the association with the younger, it cannot be said that the gain was equal. There was nothing electrical in Thoreau's intercourse with his fellow men; he gave off no spiritual sparks. He absorbed intensely, but when called upon to illuminate in turn was found wanting. It is with a sense of relief that we read of his having really been stirred into active enthusiasm anent the wrongs done the ill-fated John Brown. With children he was affectionate and gentle, with old people and strangers considerate. In a word, he loved his kind as animals, but did not seem to find them as interesting as those furred and feathered. In 1847 Thoreau left Walden Lake abruptly, and for a time occupied himself with lead-pencil making, the parental trade. He never married, thus further fulfilling his policy of what one of his essayist-biographers has termed “indulgence in fine renouncements.” At the comparatively early age of forty-five he died, on the 6th of May 1862. His grave is in the Sleepy Hollow cemetery at Concord, beside those of Hawthorne and Emerson. Thoreau's fame will rest on Walden; or, Life in the Woods (Boston, 1854) and the Excursions (Boston, 1863), though he wrote nothing which is not deserving of notice. Up till his thirtieth year he dabbled in verse, but he had little ear for metrical music, and he lacked the spiritual impulsiveness of the true poet. His weakness as a philosopher is his tendency to base the laws of the universe on the experience-born, thought-produced convictions of one man — himself. His weakness as a writer is the too frequent striving after antithesis and paradox. If he had had all his own originality without the itch of appearing original, he would have made his fascination irresistible. As it is, Thoreau holds a unique place. He was a naturalist, but absolutely devoid of the pedantry of science; a keen observer, but no retailer of disjointed facts. He thus holds sway over two domains: he had the adherence of the lovers of fact and of the children of fancy. He must always be read, whether lovingly or interestedly, for he has all the variable charm, the strange saturninity, the contradictions, austerities and delightful surprises, of Nature herself.

Cape Cod

Introduction

Of the group of notables who in the middle of the last century made the little Massachusetts town of Concord their home, and who thus conferred on it a literary fame both unique and enduring, Thoreau is the only one who was Concord born. His neighbor, Emerson, had sought the place in mature life for rural retirement, and after it became his chosen retreat, Hawthorne, Alcott, and the others followed; but Thoreau, the most peculiar genius of them all, was native to the soil.

In 1837, at the age of twenty, he graduated from Harvard, and for three years taught school in his home town. Then he applied himself to the business in which his father was engaged,—the manufacture of lead pencils. He believed he could make a better pencil than any at that time in use; but when he succeeded and his friends congratulated him that he had now opened his way to fortune he responded that he would never make another pencil. "Why should I?" said he. "I would not do again what I have done once."

So he turned his attention to miscellaneous studies and to nature. When he wanted money he earned it by some piece of manual labor agreeable to him, as building a boat or a fence, planting, or surveying. He never married, very rarely went to church, did not vote, refused to pay a tax to the State, ate no flesh, drank no wine, used no tobacco; and for a long time he was simply an oddity in the estimation of his fellow-townsmen. But when they at length came to understand him better they recognized his genuineness and sincerity and his originality, and they revered and admired him. He was entirely independent of the conventional, and his courage to live as he saw fit and to defend and uphold what he believed to be right never failed him. Indeed, so devoted was he to principle and his own ideals that he seems never to have allowed himself one indifferent or careless moment.

He was a man of the strongest local attachments, and seldom wandered beyond his native township. A trip abroad did not tempt him in the least. It would mean in his estimation just so much time lost for enjoying his own village, and he says: "At best, Paris could only be a school in which to learn to live here—a stepping-stone to Concord."

He had a very pronounced antipathy to the average prosperous city man, and in speaking of persons of this class remarks: "They do a little business commonly each day in order to pay their board, and then they congregate in sitting-rooms, and feebly fabulate and paddle in the social slush, and go unashamed to their beds and take on a new layer of sloth."

The men he loved were those of a more primitive sort, unartificial, with the daring to cut loose from the trammels of fashion and inherited custom. Especially he liked the companionship of men who were in close contact with nature. A half-wild Irishman, or some rude farmer, or fisherman, or hunter, gave him real delight; and for this reason, Cape Cod appealed to him strongly. It was then a very isolated portion of the State, and its dwellers were just the sort of independent, self-reliant folk to attract him. In his account of his rambles there the human element has large place, and he lingers fondly over the characteristics of his chance acquaintances and notes every salient remark. They, in turn, no doubt found him interesting, too, though the purposes of the wanderer were a good deal of a mystery to them, and they were inclined to think he was a pedler.

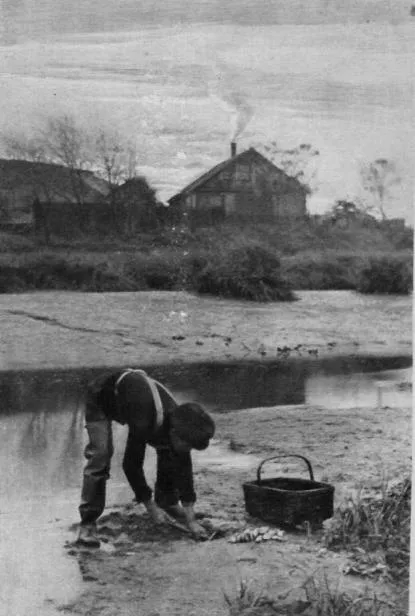

His book was the result of several journeys, but the only trip of which he tells us in detail was in October. That month, therefore, was the one I chose for my own visit to the Cape when I went to secure the series of pictures that illustrate this edition; for I wished to see the region as nearly as possible in the same guise that Thoreau describes it. Fro...