![]()

Chapter 1

Mugabe: A Revolutionary Tyrant

Before considering the historical context of the war and his leadership of the liberation struggle before his ascendancy to political power, it is important to consider the nature of the central character in this story: Robert Gabriel Mugabe.

When leaders destroy their own countries, as Hitler and Mugabe did, it usually conjures up a bedlam of pop psychologists trying to decipher the dictators’ peculiar form of madness. It is the author’s contention that Mugabe is not clinically insane – a ruthlessly consistent pattern of behaviour is apparent, with its own internal logic. Perhaps the fairest psychological assessment was made by ex-Zimbabwean Heidi Holland, a white liberal who encountered Mugabe briefly during the anti-colonial war, and later managed to secure a lengthy interview for her well-known book, Dinner with Mugabe. She worked with a group of psychologists as well as interviewing many of Mugabe’s close associates and family. Holland profiled Mugabe’s lonely childhood, Catholic upbringing, and scholarly leanings. She tried to explain his paradoxical affection for certain white leaders, especially British royalty, and his policies which led to murder and mayhem in the white farming community after 2000. Mugabe’s more than a decade of imprisonment under Ian Smith, and the refusal of the authorities to allow him to attend the funeral of his son, are quoted as part-causes of his anger towards whites. Yet Mugabe’s offer of reconciliation to whites in 1980 was almost certainly genuine. Later, he felt betrayed by Tony Blair’s Labour government in London because of its refusal to pay for white farmers’ compensation; he also felt betrayed by the fact that most Rhodesian whites, and the farmers in particular, voted continuously for the opposition, especially the MDC.

Holland describes Mugabe’s delusions of omnipotence thus:

Holland also asked Mugabe, in her long-delayed interview, how the long prison years – about one-third the term of the much more magnanimous Nelson Mandela – had affected him. She asked specifically:

‘When you came out of prison, were you the same person who went in?’

Mugabe had very few friends. One of them was Enos Nkala. In 1963 the Zimbabwe African National Union party was founded in Nkala’s home in Highfields in Harare (then Salisbury). Nkala, who had long been a faithful and fanatical ally of his leader, finally lamented that he could not stop his old colleague from blaming US presidents and UK prime ministers for all Zimbabwe’s woes. Nkala said that Mugabe was now

To those who studied his personality for years, at close hand or in the ivory tower, Mugabe appeared a mass of contradictions. His upbringing and ideology were commented on by Andrew Young, President Carter’s envoy in the late 1970s: ‘The trouble with Robert Mugabe is that when you’ve got a Jesuit education mixed with Marxist ideology, you’ve got a hell of a guy to deal with.’ Mugabe could be extremely charming, adhering to all the slow, gentle niceties of African greeting rituals; at other times, curt and rude, even to senior statesmen. Mugabe loathed his chief rival, Joshua Nkomo, and was frequently rude to him and about him. At the time of the Lancaster House peace talks in London, Julius Nyerere, the president of Tanzania, invited both men in to his study to try to mend fences, and get them to form a united front. Nkomo, as the older man, was invited in first. When it was Mugabe’s turn, he said: ‘If you think I am going to sit where that fat bastard just sat, you’ll have to think again.’ The Tanzanian leader was utterly shocked by the remark, especially as then Nyerere was the Nelson Mandela of his era. The two rivals continued to clash, but especially when Mugabe was on the cusp of victory in Zimbabwe. He refused to fight a joint campaign with Nkomo, despite the existence of the so-called Patriotic Front. When Mugabe won by a landslide at the polls, Nkomo said: ‘You give them one man, one vote and look what they do with it.’ Then, showing his bitterness at having to fight the polls alone, Nkomo said almost more in sadness than in anger: ‘We should have fought the election together … Robert let me down.’

Trevor Ncube, the eminent Zimbabwean writer and editor, recently summed up Mugabe’s disturbing psychological behaviour: ‘Not once has Mugabe taken responsibility for his decisions and the actions of those around him. He takes no responsibility for the mess that the country is in.’

Richard Dowden, the director of the Royal African Society in London, summarized Mugabe very succinctly:

As ever with Mugabe, his relationships with whites were complex and contradictory. He possessed a life-long affection for his white Catholic tutors, especially Father Jerome O’Hea. He developed an almost son-father relationship with Lord Soames, briefly the governor of Southern Rhodesia. Mugabe attended Christopher Soames’s funeral in the UK in 1987, clearly out of affection, not duty. The man he should have hated, Ken Flower, the head of the Central Intelligence Organization which had tried to kill him, became a close confidant. Flower’s personal diary is full of warm words about Mugabe as prime minister. Originally, Mugabe distinguished between good whites and bad ones. He accorded the unique honour for a white by sponsoring the burial, in the hallowed ground of Heroes’Acre, of the Welsh-born Guy Clutton-Brock. He had been an early supporter of the liberation struggle. Gradually, Mugabe’s condemnatory rhetoric lambasted all whites. It was his regime’s murder of white farmers after 2000 that fired up the Western media campaigns, which had largely ignored the destruction of so many Ndebele families in the 1980s.

Peter Godwin, in his recent book, The Fear, commented shrewdly on Mugabe’s favourite parlour game – Britain-bashing:

Nevertheless, Mugabe still wins much kudos in his own country and in the rest of Africa for his attacks on Western, especially British, hypocrisy, not least over the land issue, and for attempts at regime change, when it was fashionable under President George W. Bush. Tirades against Mugabe epitomized Western double standards in the eyes of many Africans. Even after Mugabe’s Korean-trained Fifth Brigade had slaughtered tens of thousands of Ndebeles in the early 1980s, Queen Elizabeth awarded him an honorary knighthood. In 1994 Mugabe was appointed an Honorary Knight Grand Cross in the Order of the Bath. This entitled him to use the letters GCB after his name but not to use the title ‘Sir’. It was only much later, in 2003, after the killing of a small number of white farmers, that the British prime minister was asked in parliament whether Mugabe should be stripped of his title. In June 2008, the Queen annulled the honour.

Britain, as the ex-colonial power, had to stand back from much of the power politics in the days of Mugabe’s decline. The dominant player was always South Africa. And yet President Thabo Mbeki, the man tasked to try to bring a settlement to Zimbabwe, was somewhat in awe of Mugabe. Despite their arguments, Mbeki was said to be personally fond of him. Normally, Mugabe insisted on being the dominant intellect in any company, but with Mbeki there was often a meeting of minds, as fellow intellectuals. Also, Mbeki showed traditional respect for the older man, especially a liberation hero.

When the author interviewed Mugabe in late-January 1980, the initial impression was of a towering intelligence. Many of the white Rhodesian politicians were dull backwoodsmen, but Mugabe stood out not only in his own country, but in the whole continent. Bolstered by seven university degrees, most secured in prison via correspondence courses, he seemed very quick-witted. Ironically, for a man who had just come out of a savage bush war as the leader of a tough guerrilla army, now immaculately dressed he minced when he walked. And his diction was almost contrived to emulate the received pronunciation of the BBC’s best Home Counties accent.

In short, Mugabe’s personality was complicated, and so were his politics. This book tries to decode Mugabe, his methods and his military apparatus. It is too easy simply to label him mad. He may have surrounded himself with yes-men, like many tyrants, but his rise to power, and his skill in hanging on to it for over thirty years, need to be seen as part of Zimbabwe’s often violent history.

![]()

Chapter 2

White Conquest of the Land: The First Chimurenga

The formal conquest of what became Rhodesia was orchestrated by Cecil John Rhodes, the tycoon who inspired the name for the British colony. Rhodes’s invasion of the lands north of the Limpopo, which legend depicted as the location of King Solomon’s mines, was the gamble of a megalomaniac with the wealth to indulge his fantasies. Rhodes secured by deceit a mining concession from Lobengula, the Ndebele king who claimed dominion over most of the territory between the Limpopo and the Zambezi rivers. He used it as a legal basis to secure a Royal Charter from the British Crown, which empowered him to establish a settler state in Mashonaland ruled by Rhodes’s British South Africa Company.

In 1890 several hundred men of the British South Africa Company’s Pioneer Corps and Police, the kernel of the self-contained frontier society, defied Lobengula’s threats to unleash the tens of thousands of warriors in his regiments. He had belatedly realized his folly and forbidden the settlers’ entry. Outsmarted by Rhodes’s multinational corporation, Lobengula was also over awed by his own fearful perceptions of the white man’s military technology. He had heard reports from the frontiers of South Africa of the overwhelming firepower of white armies. The Ndebele king allowed himself to be browbeaten, and so let the columns of the Pioneers roll over the veldt to establish the Company state in Mashonaland. Its tenuous links with the outside world were guarded by a string of tiny forts, but its greatest security was Lobengula’s chronic and ultimately fatal vacillation.

The settlers’ dreams of finding an African Eldorado were shattered in the lean years which followed the invasion, but stories were still repeated endlessly of gold deposits – just beyond reach within the borders of the Ndebele heartland. In 1893 the Trojan horse reluctantly accepted by Lobengula into his domains − which he refused to destroy despite the demands of a hot-blooded Ndebele war party − fulfilled his worst fears. The Company cleverly engineered a war in which the Ndebele were marked as the aggressors. Columns of settler volunteers, tempted with promises of farms and mining claims, converged on Gubulawayo, the Ndebele capital, and on the way fought two encounter battles with Lobengula’s brave but outgunned regiments. Shortly before his capital was captured and sacked, the defeated king fled north and died in the bush beyond the grasp of pursuing settler patrols. The victors carved the defeated kingdom into farms and mines, seized and distributed the Ndebele national herd as war booty, and built a new frontier town, Bulawayo, on the site of Lobengula’s razed capital.

![]()

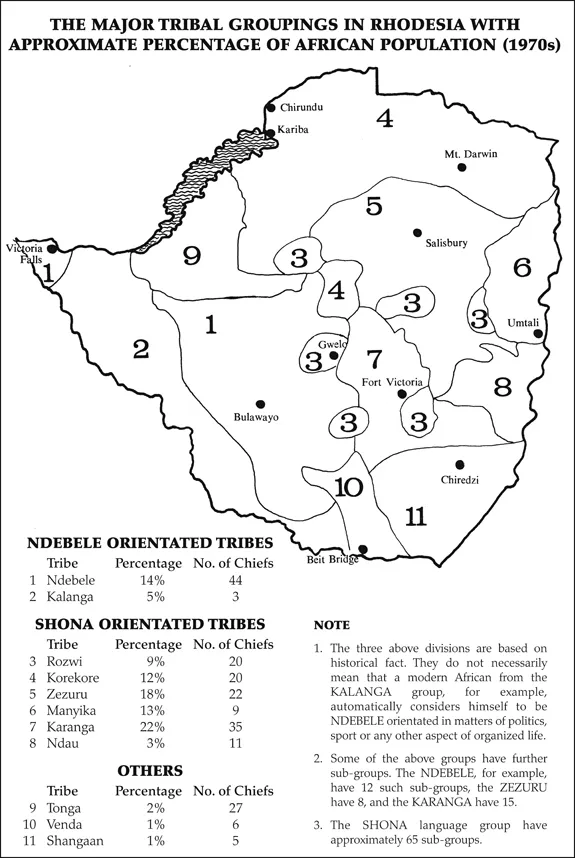

Map 1 – The Major Tribal Groupings in Rhodesia

![]()

Rhodes’s successes stoked the fires of his megalomania. As well as controlling vast financial operations in Southern Africa, he was prime minister of the Cape Colony. He was concerned about the growth of Afrikaner nationalism in South Africa and sought to exploit the grievances of the English-speaking mining community in Johannesburg to engineer the overthrow of Paul Kruger’s South African Republic. The new country of Rhodesia was to be used as a springboard for Rhodes’s illegal conspiracy, which was planned in deep secrecy to prevent the intervention of the Imperial government.

In late 1895, BSA Company forces struck south to precipitate a coup against the Afrikaner republic in the Transvaal. But the so-called Jameson Raid was a humiliating fiasco for the Company and its soldiers. It also invited catastrophe in the colony. The Ndebele and Shona, chafing under the Company’s regime of forced labour, cattle and land seizures, as well as its arrogant administration, and suffering from the natural afflictions of cattle disease and locusts, rose against the settlers while the country was denuded of its armed forces.

The Company had not completely shattered the Ndebele and Shona political systems, and these, aided by the religious systems of the two peoples, organized countrywide insurrections which decimated the settler population. Ndebele warriors dug up the rifles and assegais they had cached after the war of 1893. The Shona had never been disarmed. The resistance raged for eighteen months. The settler forces, bolstered by contingents of British troops, were hampered by poor logistics and shortage of horses. The insurgents made good use of their superior bushcraft and intelligence network, and avoided the sort of setpiece confrontations which had bloodied Lobengula’s regiments in 1893. The Company forces eventually adopted scorched-earth tactics to starve out the rebels, who then retreated to hilltop strongholds and into caves from which they were systematically dynamited. Thus ended the first Chimurenga.

Rhodes’s hubris cost him the premiership of the Cape Colony, although his influence was strong enough to save him from gaol for illegally launching the Jameson Raid. Only the British government’s reluctance to administer Rhodesia prevented the abrogation of the Royal Charter to punish the Company for its abuses of power. As well as leaving the Company’s powers largely intact (though more closely supervised by Imperial officials), the events of the later 1890s bequeathed a legacy of bitterness to both racial groups. The settlers suffered from a ‘risings psychosis’, a morbid fear of another unexpected storm of violence. Africans were characterized as treacherous and barbaric, for in the first days of the insurgency hundreds of near-defenceless homesteaders living on lonely farms were taken by surprise and brutally murdered. Africans saw their hopes of throwing off the yoke of Company rule disappear in the smoke of Maxim and Gatling guns and the blasts of dynamite. The death and destruction they suffered passed into their folklore.

Although Rhodesian forces fought alongside British and Imperial units against the white Afrikaners during the Boer War, the settlers remained mesmerized by the spectre of an African rebel lion. The defence system of the first decade of the twentieth century was geared solely towards securing the settlers against the vastly more numerous black population. Imperial supervision forced the Company to develop more subtle ways of controlling the African masses. Forced labour was no longer possible, but in creasing taxation compelled African men to seek work in the labour-hungry settler economy to meet their obligations to the tax-man. Registration certificates and pass laws controlled the movements of Africans, and the boundaries of their reserves were strictly defined. African peasant farmers were moved off their ancestral lands to make way for Europeans, and armed police patrols crisscrossed the territory to display the power of the Company and to nip thoughts of insurrection in the bud.

The white man’s war of 1914-18 resurrected fears of an opportunistic African rising. Internal defence remained a top priority throughout the war against the Germans. Several thou sand Africans enlisted in an all-volunteer force, the Rhodesia Native Regiment. The unit saw action in German East Africa. The settlers swallowed their repugnance at the thought of arming and training the possible core of some future African insurrection, and of undermining the myth of white supremacy by putting Africans into the field against white Germans.

The Twenties and the Depression years saw a widening of racial divisions in Rhodesia. T...