![]()

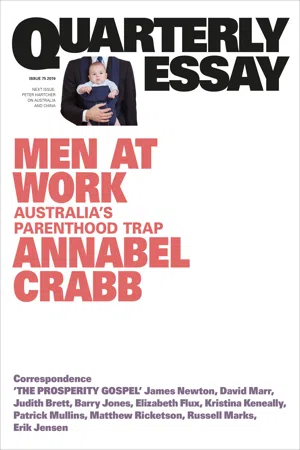

MEN AT WORK | Australia’s parenthood trap |

| | Annabel Crabb |

In June 2018, a child was born. It seemed – from what I could tell, allowing for the array of crocheted blankets in which it was swaddled – a very sweet but otherwise unremarkable infant. Two button eyes, a nose, probably bipedal, and so on. And yet this was one of the most celebrated and controversial children the Southern Hemisphere has encountered this decade.

Why? Because her mother is the serving prime minister of New Zealand.

Baby Neve’s mother, Jacinda Ardern, was hammered during the September 2017 election campaign with questions on her specific intentions vis-à-vis the biological equipment with which she – at birth – had been endowed and which in her thirty-seven years she had yet to engage fully in pursuit of her biological destiny. And when she finally announced her pregnancy – well. All bets were off. In Australia, she became the most remarkable New Zealander since Russell Crowe, or Phar Lap. No matter that Ms Ardern was not even the only New Zealand–born political leader to make a baby that year (the Australian deputy prime minister, Barnaby Joyce, having unexpectedly shared line honours in that respect). As the New Zealand prime ministerial ankles swelled, so did the column inches of advice, congratulation and condemnation extended to this woman on a mission which – as readers were tirelessly reminded – no woman had attempted since Benazir Bhutto. (And look what happened to her.) From Angela Shanahan, at The Australian:

There are the simple practical issues: the three- to four-hourly feeds for which, being a greenie leftie, she will try to do using her own milk; the sleepless nights, which reduce many women to a zombielike state; and the blithe confidence that after six weeks her partner will take over as full-time caregiver. Well, good luck with that one, too, because the father is not the mother and there is such a thing as maternal bonding, which is a basic post-partum physical need for mothers and infants. This woman needs at least six months off, not six weeks.

On both sides of the Tasman, the logistics of Ardern’s post-partum schedule were a question on which everyone, it seemed, had an urgent opinion.

A little over a year later, the Liberal Party of Australia – in one of its increasingly customary leadership coups – tipped out the serving prime minister, Malcolm Turnbull, and his deputy, Julie Bishop, and replaced them with Scott Morrison and Josh Frydenberg. Morrison and Frydenberg were something of an ecclesiastical first. The nation had never had a Pentecostal prime minister before, let alone one serving with a Jewish deputy and treasurer. Morrison immediately made the crippling national drought his primary concern, advocating prayer for rain; two days after his elevation, Bourke Airport recorded its highest single-day rainfall on record, suggesting that – in Bourke at least – the Almighty may have had an ear pricked. But there was something else unusual about the pair. Not since the mid-1970s, when Malcolm Fraser appointed a young John Howard to be his treasurer, had these two positions been held by the fathers of young children. Morrison’s daughters, Abbey and Lily, were both at primary school. Frydenberg’s kids were even younger: Gemma a preschooler, Blake a toddler.

One can only imagine the sustained national heart attack that would have accompanied the appointment of two mothers of young children to these demanding jobs. And we do need to rely on our imaginations, as no woman with children of any age has ever served as prime minister, or treasurer, or indeed as deputy leader of the Liberal or Labor parties in government. However, the first joint press conference given by the two men came and went without anyone raising the question that almost certainly would have been the first asked at an all-mothers affair: “How are you going to manage it all?”

Now, this essay isn’t going to be a lengthy whine about how life is tough for Jacinda Ardern and easy for Scott Morrison. I’d never argue that. But parliament is – in many respects – a brightly lit model village of our national sentiment. It’s an absolutely intriguing demonstration of what we expect from fathers that the question of work–family balance – for a parent with the biggest job in the country – doesn’t even come up. For three weeks, Morrison and Frydenberg were interviewed about everything from faith to football to their favourite songs. I tweeted my observation about both of them having young families and was immediately accused by some anonymous snarler of “trying to humanise them.” Right, I thought. I can hardly complain about nobody asking them how they are going to manage things if I can’t be bothered to do it myself. So I called them both.

And the first thing that became obvious was how unaccustomed each of these men was to considering this question. Working mothers of any public profile or professional seniority are asked how they “manage it all” with such lavish regularity that their answer is like a little psalm they know by heart. Here’s mine: “Well. Mondays Jeremy works half a day from home, so that’s my day of working like a normal person. Thursday and Friday the kids are at after-school care, Tuesday and Wednesday are a crapshoot; sometimes I’ll come home from work for school pick-up and go back to work after they’re in bed, or hit up the favour bank, which – in my neighbourhood of school parents – is a busy institution of daily withdrawals and deposits. (I’ll pick your kid up from piano on Tuesday if you’ll take mine to gymnastics Wednesday. I’ve got a vat of bolognese sauce to feed ten kids if you’ll look after mine for a few hours from three.) I do most of the cooking; Jem does grocery shopping, laundry and school forms. Some days it all works smoothly. Some days it’s a debacle.”

Working mothers are so used to comparing notes on how they manage it all that it’s practically a language. But what I realised quickly when talking to the prime minister and treasurer was that they are not fluent. Here’s what the treasurer said:

Whenever I am away, we use FaceTime a lot, and whenever I am at home I do stories, milk and bed, and try to play as much ball sports and Lego as possible. Running races at the park [is] also a regular. We always have Friday night together as a family meal, which is always special.

And here’s the prime minister:

The first point is that none of this would be possible without the kids having an amazing mum. That’s true for me and for Josh. But it’s about priorities. Little rituals are important. You’ve got to talk every day and we try to do it twice a day. We do FaceTime when we can. Little things, like: ‘Where are you today?’ You hold the camera phone up and you show them where you are. My kids have grown up while I was in politics and I think that’s a good thing, on balance, because life is more normal to them. Jen and the girls almost never come to Canberra. We have our friends and our family that we socialise with and they’re very disconnected from the world of politics. It means our kids are growing up in a normal environment and that’s very important to us.

With both men, I had to rephrase the question several times to explain what I was getting at: “How does it work? How do you manage, day to day?” And what became clear was that both their models were about coping with or compensating for absence. FaceTiming every day or dining together once a week is an expression of parental love and devotion – and very important it is too – but it doesn’t contribute much practical horsepower to the engine that keeps a family running. Who does school pick-ups? Who remembers to take them to the dentist? What happens when they’re sick? Their spouses do most of that stuff.

And while handing over the lion’s share of parenting to a spouse is the stuff of international headlines when it’s Jacinda Ardern, when it’s Scott Morrison it’s so unremarkable as to occasion no comment whatsoever.

Now, I would never question the love or commitment of either man to his children; both Scott Morrison and Josh Frydenberg are exceptionally besotted with and close to their kids. What I want to know is: why do we expect so little of fathers? Why do we fret so extensively about the impact on children of not seeing their mothers enough, but care so little about what happens when it’s Dad who’s always away? Do we think dads are just for weekends? Or are we simply so roundly prepared – based on what we see – for their absence that we neither mourn it nor remark on it?

In August 2014, the Silicon Valley executive Max Schireson wrote a fascinating blog post. He was the CEO of his own madly successful enterprise, but used his personal blog to announce that he was stepping down because constant travel made it impossible to spend enough time with his three young children. The stress of constant separation was – for him – the biggest issue in his life, and he was mystified that in all the press attention he received, this was the one question that was never asked of him:

As a male CEO, I have been asked what kind of car I drive and what type of music I like, but never how I balance the demands of being both a dad and a CEO. While the press haven’t asked me, it is a question that I often ask myself. Here is my situation:

I have three wonderful kids at home, aged 14, 12 and 9, and I love spending time with them: skiing, cooking, playing backgammon, swimming, watching movies or Warriors or Giants games, talking, whatever.

I am on pace to fly 300,000 miles this year, all the normal CEO travel plus commuting between Palo Alto and New York every two to three weeks. During that travel, I have missed a lot of family fun, perhaps more importantly, I was not with my kids when our puppy was hit by a car, or when my son had (minor and successful, and of course unexpected) emergency surgery.

I have an amazing wife who also has an important career; she is a doctor and professor at Stanford … I love her; I am forever in her debt for finding a way to keep the family working despite my crazy travel. I should not continue abusing that patience.

I’d always been quietly enraged by the interviews with female CEOs that start with the question of how they manage their families along with their jobs. But reading Schireson’s post made me change my mind completely. Now I don’t get mad when female leaders are asked that question. It’s a bloody sensible question. Now I just get mad when male leaders aren’t asked it. Not asking is actually, in itself, quite a powerful message. It says, “No one expects you to care about this.” It says, “It’s not your job to worry about that stuff.” It says, “Whatever efforts you do make, or whatever private griefs your big job cloaks, are not of interest to anyone.” And for an increasing number of young fathers who do want to live their lives differently from the way their own fathers did, that’s an insult.

It’s an antiquated view of what fatherhood is. But it’s a view that is reinforced every day, at all levels of Australian society, at both a formal and a casual level. From the moment that sperm hits egg, we treat mothers as the proper parents and fathers as their gormless accessories. We have a national paid parental leave scheme for the primary caregiver, and an ancillary mini-scheme for the other parent. We have “mothers’ groups” for the parents of babies. We have the term “working mum” for a mother who works, as if that’s special enough to be surprising. But “working dad” isn’t a thing people say.

Half a century of modern feminism has changed the way women conduct their lives almost beyond recognition. But men are still in their old box. And the risk implicit in this arrangement is bigger than just insulting a generation of fathers who want to do things differently. This is an age in which the #MeToo movement has pricked the world’s ears to the stories of women. In which some large organisations adopt formal programs geared to increasing the number of women in leadership positions. Young men arrive in these workplaces who have never sexually harassed anyone, and yet feel the uneasy legacy of Harvey Weinstein and his ilk. These young men have commonly been outperformed at school and university by their female peers, and yet may find their new workplaces have schemes in place to increase the rates at which women are hired or promoted. How galling is it for this generation of men (who, as we shall see, are keen to be more involved with their children than their own fathers were) to find that flexible work and parental leave are still options reserved largely for women? Discrimination against men in the area of parenting is commonplace; it’s even – as I shall explain – sanctioned by Commonwealth law. And this discrimination underpins ancient structures that disadvantage not only men, but women and children too.

In this essay, I want to do something that’s isn’t done enough: look squarely at men and how they work, and how their working lives change – or rather, don’t change – when they become fathers. Too often, gender equity in workplaces is just a debate about what happens to women. How many of them get promoted, what the barriers are, and so on. But what about the expectations that the workplace imposes on fathers? What are the invisible rules that prevent men from seeking flexible work and parental leave the way women do? This is a worthwhile question just for men’s sake, and for the sake of their children. But it’s also worth asking for women’s sake. Because, of course, so long as women and men continue to hook up and make babies together, the way men work and live will be a significant constituent element of the choices that women are able to make.

![]()

THE NATURAL WAY OF THINGS

So let’s go back to New Zealand for a moment and broaden our gaze. For all the headlines about Jacinda Ardern, the person who made it possible for her to serve as a rare breastfeeding world leader is – to a significant extent – her husband, Clarke Gayford, who was named in the role of primary carer when the NZ prime minister’s pregnancy was announced. And so it was that Mr Gayford – formerly the genial and unnecessarily handsome presenter of a fishing program – shuffled into the most conflicted occupation a modern man can attempt: the Stay-at-Home Dad.

I call it the Hero–Zero complex. On one hand, the Stay-at-Home Dad tends to be lionised. Often by women, who are so intensely thrilled by the idea of a bloke who would shoulder responsibility for remembering whose birthday party it is on Saturday and whether it’s Mufti Day tomorrow that they actually want to touch the guy, not in a sexy way but just to make sure he’s real. The congratulation of the Stay-at-Home Dad in such circles can be over the top. Crazy. Hyper-excitable. Which is unfortunate, because then the Zero factor kicks in. This is where the Stay-at-Home Dad is treated as though he has ceased to exist, or has chosen a way of life of no significance whatsoever. Typically, this treatment comes from former workmates who stop inviting him to things and, when they do run into him, say awkward things like “Still being Mister Mum, then?” or “So when are you coming back to work?”

Were he a woman, Clarke Gayford would be unremarkable. He’d join the dignified ranks of political spouses who for centuries have attended school plays with plenty of room on the neighbouring seat to store their handbags. But he’s a fellow, so his Hero–Zero complex kicked in pretty fast once the happy news of the pregnancy was announced. He swiftly felt the ugly undertow of what happens, in this social media age, when men and women do the reverse of what underlying gender expectations silently but powerfully command them to do. More or less immediately, a subterranean online gossip campaign engulfed the man, so intensely that the couple were obliged to protest publicly. Conspiracy websites canvassed everything from Mr Gayford’s alleged excessive partying to the proposal that Ms Ardern was a notorious transsexual who was faking her pregnancy. You might laugh, or at least raise a sceptical eyebrow. But entire books have been written about the theory that Sarah Palin faked her pregnancy in the 2008 US election campaign. Some people take this sort of stuff seriously. And in Mr Gayford’s case, we can wearily recognise some of the treatment handed out to Peter Davis, the spouse of New Zealand’s preceding female prime minister, who for decades was accused of being a front for his wife’s lesbianism. Or indeed to Tim Mathieson, the spouse of Australia’s first female prime minister, who also was accused (accurately) of being a hairdresser and (inaccurately) of being a front for his partner’s lesbianism, and asked publicly by a radio presenter whether it was true that he was gay. (This fascination with Tim Mathieson’s occupation as a hairdresser always confounded me. My firm view has always been that a woman who needs to be TV-ready by 6 a.m. most mornings and who hooks up with a hairdresser is crazy like a fox.)

It is at once extraordinary and predictable the way public figures can be punished for violating the roles that their gender recommends they play. And it’s also extraordinary how unoriginal those punishments are, from country to country. It gives us a sniff of what sort of attitudes might meet ordinary men who take on the role of stay-at-home fathering and are not married to a world leader.

This seems a good moment to check how many such men there are. In the past decade, there’s been quite a bit of chat about stay-at-home dads. There’s been a popular TV show featuring handsome SAHDs. There have been articles, think-pieces, support groups, days of action – all sorts. And yet the actual number of stay-at-home dads in Australia remains stubbornly stagnant. About 4 per cent of Australian families with kids under eighteen had stay-at-home fathers in 1991. These days, according to the latest census, it’s 5 per cent. So we’ve ticked up one percentage point in twenty-five years. Barely a change; for all the talk, stay-at-home dads are still the black swan of parents.

But plenty else has changed over that time. For instance, the proportion of stay-at-home mums has decreased from 33 per cent to 27 per cent. And the proportion of households with both parents out of work has decreased from 12 per cent to 7 per cent. Where’s everyone gone? “To work” is the answer. Between 1991 and 2016, the proportion of family households in which both parents work rose from 52 per cent to 61 per cent. Two-income families are now the norm.

More parents working should – you’d think – generate a new round of juggling as parents thrash out new ways of ensuring kids are fed, bathed, played with and ferried to and from school around work hours. And you’d be right....