This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

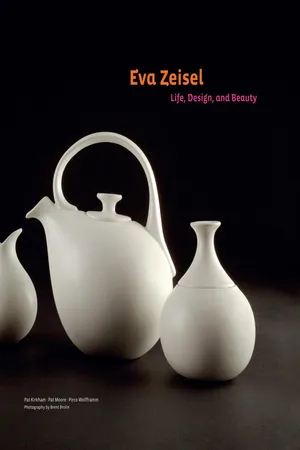

About This Book

Eva Zeisel was one of the twentieth century's most influential ceramicists and designers of modern housewares. Her distinctive take on modern industrial design was inspired by organic form and brought beauty and playfulness to housewares, earning her designs a beloved place in midcentury homes. This richly illustrated volume—the first-ever complete biographical account of Zeisel's life and work—presents an extensive survey of every line she ever created, all captured in gorgeous new photography, plus 28 short essays from scholars, collectors, curators, and designers. The definitive book on the grande dame of twentieth-century ceramics, this is an essential resource for anyone who appreciates modern design.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Eva Zeisel by Pat Moore, Pirco Wolfframm, Pat Kirkham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Product Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

DesignSubtopic

Product DesignEVA ZEISEL: DESIGN LEGEND 1906–2011

Pat Kirkham

A hugely talented designer with a tremendous life force, Eva Zeisel (born 1906, Hungary; died 2011, United States) was a major figure in the world of twentieth-century design, and both her work and her approach to it inspired, and continue to inspire, younger generations of designers. Eva worked in Hungary, Germany, and the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s and was the preeminent designer of mass-produced ceramics for domestic use in the United States in the 1940s, 1950s, and early 1960s. During her extensive career she also worked for companies in Mexico, Italy, Hungary, England, Russia, India, and Japan. She was honored with many prestigious awards, from honorary degrees to two of the highest awards open to civilians in her native Hungary.

Introducing Eva

This chapter introduces Eva’s ideas, work, and life in all their varied aspects in the hope that readers will gain a better understanding of her as a person and of the breadth, variety, and quality of her designs. As part of setting these topics within the wider histories of which they were part, and assessing the various influences upon Eva and her formation as a designer, I seek to broaden, and sometimes challenge and revise, current understandings of them. I am interested in telling history in many ways and through many “voices,” including oral history, memoirs, images, and anecdotes, as well as through more formally academic and analytical modes, and I have tried to weave Eva’s own and very distinctive voice throughout this chapter. I loved hearing her talk, loved talking with her, and hope that something of that experience will resonate with readers.

Her work has been the subject of many exhibitions, as well as the film Throwing Curves, a documentary about Eva and her work released in 2002. By the end of this chapter, readers may well feel that a Hollywood biopic or a novel would be more fitting. Indeed, her experiences during her sixteen-month incarceration in a Soviet prison in the 1930s were a source for Darkness at Noon (1940), a novel by Arthur Koestler (1905–1983), a childhood friend of Eva with whom she had a love affair in Paris in the 1920s.1

So, too, were the prison experiences of the Austrian physicist Alexander Weissberg (1901–1964) to whom Eva was married (though separated) at the time of her arrest.2 Weissberg placed himself in considerable danger by trying to help Eva and narrowly avoided death on several occasions, including when, like Eva, he was falsely accused of plotting against Soviet leader Joseph Stalin; when he was handed over to the German Gestapo by the Soviets; and when fighting with the Polish underground during World War II. Eva’s departure from Vienna on one of the last trains out of the city in March 1938 as the German army marched in, coming as she did from a family of assimilated Jews, was yet another drama-packed episode of what was, by any estimation, a most remarkable life.

One of the joys of studying a designer who worked in the world of mass production for most of her career is that thousands of pieces made from her designs continue to circulate, some of them still used by those who first bought them, or by their descendents. Some objects found their way into museum collections at the time, and many more have followed. The Museum service was created with the intention of producing heirloom-quality pieces and the Tomorrow’s Classic line was named to suggest such a future. Today many of Eva’s other designs have also acquired heirloom status.

As a designer, Eva thought of herself as working in a modern way, but long before she thought about herself as a designer of any sort, she thought of herself as modern. As a child, she was conscious of the modernity of the world into which she had been born.3 The family, and the circles in which family members moved, believed that the new century would reap all the benefits of the progress made during the previous century while realizing even greater achievements. Children born in the new century were considered more fortunate than those from earlier generations and symbolized the hopes of a better world.4 She recalled:

When I was about six years old I was read to from a small volume . . . It was the memoir of a doll who started her story as follows, “I am a modern doll who prides herself on having been born at the end of the superb nineteenth century which one can call the century of miracles, of the triumphs of technology. Evidently it is to the science of technology that I owe the suppleness of my limbs, my uncertain speech, and the grace of movements unknown to my forebears.” Out of the miracle of technology, this doll, who has shed the dullness, the passivity of other dolls, and had acquired intelligence and feelings, was able to tell her life story.5

Eva at Brooklyn Botanic Garden, 2006. PWA.

Eva liked to describe herself as a “modernist with a small m.”6 The lower case is enormously important. It marked her distance from the architecture and design movement in interwar Europe, known as the Modern Movement. That movement grew out of several overlapping progressive and avant-garde trends in Europe, from Russian Constructivism and De Stijl in Holland to the Bauhaus in Germany and architect-designers such as the Swiss-born but French-based Le Corbusier, who famously described a house as a “machine à habiter” (machine for living in). Its adherents (Modernists with a capital M) took a rationalist, functionalist, and problem-solving approach to design, and advocated new materials, new technologies, and industrial mass production to produce objects and buildings appropriate for what they thought of as the new “Machine Age.”7 For the most part, they rejected both decoration and looking to past styles for inspiration (historicism).

Eva, like many others, welcomed the social agenda of bringing affordable, well-made, and well-designed goods to greater numbers of people, but felt that few designers or reformers of any worth in the late 1920s or 1930s would oppose such a notion. She believed that this should be a given, a starting point for any designer rather than a mantra unto itself, and was skeptical about the Modern Movement’s claim that style had disappeared. When I told her that British designer William Lethaby dubbed it the “No-Style style,” she chuckled, clapped her hands with glee, and said she wished that she had coined the phrase.8 Eva thought of the world in far broader terms than a “Machine Age” and considered Modernist designs to be the result of narrow-minded people obsessed with “so-called functionalism, anti-historicism, and the ridiculous idea that form followed function.”9 Eva was just as interested in everyday objects as Modernists but took a much more open-ended approach to design, while always respecting historicism.

She insisted that “the designer must understand that form does not follow function, nor does form follow a production process,” adding, “For every use and for every production process, there are innumerable equally attractive solutions.”10 Eva sought “soul contact” with users and found Modernism to be insufficiently cognizant of the user, too patronizing and didactic, and inherently dangerous, because its narrow definitions of “good design” radically limited variety and choice, especially when it came to the vocabulary and outlook of the designer before he or she had even begun to consider the particular commission or problem at hand.11 The role of the designer, as she saw it, was to go beyond applying rationalism to the task at hand and evoke the more psychological and aesthetic dimensions of design.12 She was not alone in holding such ideas, but her articulation of them through notions of playfulness and beauty was distinctive. Her emphasis on “the playful search for beauty” was both modest and hugely ambitious, as we shall see throughout this book.

Eva’s ideas and designs offer an excellent case study for seeing European modern design of the interwar years through lenses other than that of the Modern Movement, especially the Bauhaus. The stories of Eva’s modernism, and the designs of many others who thought of themselves as modernists with a small m, need to be told for their own sakes, but they also need to be told to redress the balance of histories too often written from pro-Modernist points of view.

The disillusionment with Modernism and the greater impact of postmodern ideas from the mid-1970s and 1980s (in some cases earlier) underpinned reassessments of several major designers who, each in their own ways, at some point stood aside from orthodox Modernism, including Alvar Aalto, Charles and Ray Eames, and Eva. All four were about the same age: Aalto was eight years older than Eva, while Charles Eames was just one year younger and Ray Eames six years younger. The more organic forms of the 1930s and 1940s were central to what Eva called the “wider aesthetic history” of which she was part, and Russel Wright, an important figure in bringing the forms of what today is often referred to as “Organic Modernism” to pottery design in the U.S., was only two years older than Eva.

Unlike Aalto, who came to stress the human and humanistic aspects of design after something of a love aff...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Foreword

- Poem: “Life”

- Part One: Eva Zeisel: Design Legend 1906–2011

- Part Two: Designs and Commissions 1928–2011

- Part Three: Taxonomy (Shapes, Bottom Stamps, Patterns)

- Part Four: Endmatter

- Select Chronology with entries on Ohio Potteries Child Toiletries, Loza Fina, Goss China: Wee Modern, Watt Pottery: South Mountain Stoneware, The Tea Council, Original Leather Stores, Acme Studios, Chantal: Eva Kettle

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author