![]()

1 Introduction to Planetary Health

Jennifer Cole

Royal Holloway, University of London and University of Oxford,UK

1.1 Introduction

Humans are not separate from the environments in which we live. We are integrated with them through the air we breathe, the water we drink, the food we eat and the waste we produce. Even within ourselves, the human body does not represent a single organism but a complex biological system (Bono-Lunn et al., 2016). Many of the cells within us come from bacteria, viruses or other microorganisms with which we coexist, and which help or hinder our interaction with the wider, external environment (Rook et al., 2017). We are an integral part of the wider biosphere of Earth.

The proper functioning, resilience and diversity of Earth’s biosphere determines the health of the planet and those who live on it, but this is now under severe stress (Steffen et al., 2006). Over the past 10,000 years, since the beginning of agriculture and the emergence of the first cities, humans have altered the environment to benefit our own species without due consideration for the impact this has on others or on the Earth itself. We have removed finite resources such as iron, coal, oil and gas (Geels et al., 2017; Sovacool, 2016). We have polluted air, water and land and have depleted potentially sustainable resources such as forests, soil micronutrients and marine life at rates that nature cannot replace. The impact of this on the environment is well documented (MEA, 2005; Landrigan et al., 2018). The way in which human health is changing, thanks to advances in sanitation and medical science, is also well understood – smallpox has been eradicated completely (Henderson, 2017), rubella has been eradicated from the Americas, and we are on the brink of seeing global success in polio eradication (Cochi et al., 2016). But as the risk from infection decreases, rates of heart disease and cancer are rising (Horton and Sargent, 2018) – driven by changes to land use, energy production, air quality, longer life and the lifestyle choices we make.

1.2 Human Health and the Environment

Exactly how the environment impacts human health is complicated, however, particularly at the global level. On average, we are living longer than ever before: human life expectancy has risen from 30–40 years before the 19th century to more than 80 years in some parts of the world today, with a global average life expectancy at birth of 71.4 years in 2015 (WHO, 2015). In the 19th century, only 50% of children survived to their fifth birthday, whereas in most developed countries today, child mortality is a fraction of 1%. Between one in 100 and one in 200 births resulted in the mother’s death, compared with just two to three in every 100,000 in some countries today. In this respect, the Earth of the 21st century is a healthier environment for humans than it ever was in the past.

This is not only related to the food security agriculture can offer and the services and more stable environment of cities, however: medical science also plays an important part. Many previously fatal conditions, such as cancer, diabetes and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection can now be managed with medical care.

We are becoming complacent about the state of the natural environment, however. Progress and development provide clean water and sanitation to urban populations, wiping away diarrhoeal disease and infection, but they also pollute that same population’s air through the use of carbon fuels, uncontrolled vehicle emissions and industrial chemicals (Lelieveld et al., 2015). Moreover, access to this progress is extremely uneven: in 2016, one in eight people worldwide did not have access to electricity, rising to nearly one in four in rural areas (World Bank Data, 2018).

Reports such as Safeguarding Human Health in the Anthropocene Epoch: Report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on Planetary Health (Whitmee et al., 2015; Haines, 2016), the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study (GBD collaborators, 2016) and the World Health Organization’s Preventing Disease through Unhealthy Environments (Prüss-Üstün and Neira, 2016) estimate that in 2015, as many as 12.6 million deaths globally – 23% of deaths worldwide – were attributable to environmental factors that could be eliminated or avoided. Out of 133 diseases or injuries considered in GBD, 101 have significant links with the environment (Prüss-Üstün and Neira, 2016).

Scientific and medical progress has given us the ability to offset ill health with treatment – if we can afford to pay, but many cannot. Vast disparities in health between different countries are tied closely to their level of economic development, affecting life expectancy at birth and the incidence and type of ill health that impacts their populations throughout life (OECD, 2017). Such disparities are even apparent within countries, based on socio-economic status, ethnic group and gender (Hotez et al., 2016). Exposure to environmental risk factors such as air pollution and contaminated water supply is often much higher in low- and middle-income countries than in high-income ones. If we placed more value on the environment, and the impact it can have on health, we may be more inclined to protect it – and the health of those who live in it into the bargain.

1.3 Human Health and Environmental Change

Whereas the academic fields of global health and one health consider the impact of the environment on the health of humans and animals today, planetary health is concerned not only with the current state of the Earth but also with environmental trends and the impact they may have on future generations. Environmental change is as important as the prevailing environmental conditions.

Global environmental change is closely associated with the forces of the Great Acceleration (Steffen et al., 2007) (see Chapter 2, this volume), a profound transformation in the relationship between humans and the natural world that began in the middle of the 20th century and which has influenced all components of the global environment since: the oceans, the atmosphere and land. There is increasing evidence that global environmental change harms human health through a variety of direct and indirect pathways leading from these accelerations. Major adaptations to the drivers of these trends, such as a move towards the use of cleaner energy and the development of less damaging agricultural practices, are needed to ensure that the environment is sustained for future generations.

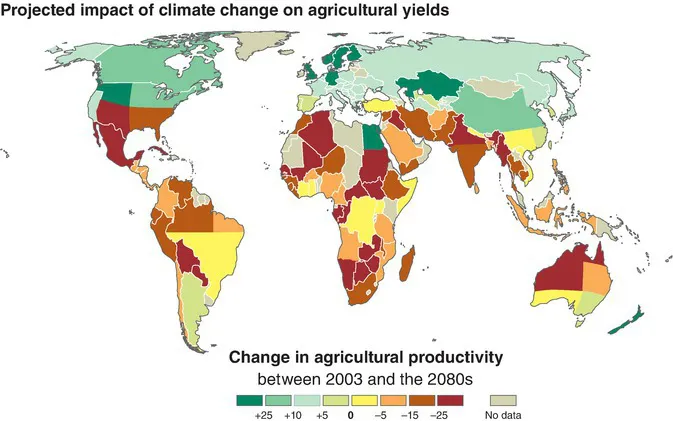

For public health experts, environmentalists and policy makers to support such adaptations, a strong understanding is required of the relationship between human health and the environment, how it has changed over time, how it is likely to change in future (Fig. 1.1), and how human culture and psychology influences the problem space as well as the solutions. This book aims to provide a starting point towards that end, by helping readers to understand how the conceptual underpinning of the Great Acceleration helps us to understand how environmental change impacts on humanity and to recognize the urgency with which we need to act.

1.4 A Systems Approach to Planetary Health

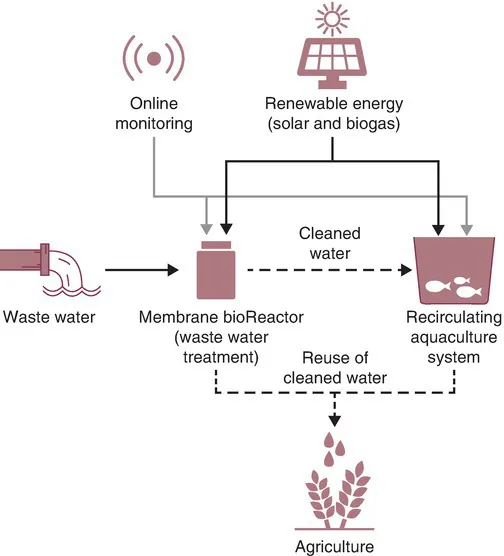

A particularly valuable aspect of the Great Acceleration framing is that it immediately places both the changes and the drivers of change within two parallel systems – the Earth system and the socio-economic system – that influence, and are influenced by, one another. The Earth system is influenced by chemical flows such as nitrogen and phosphorus into agricultural land, the atmosphere and water courses. These flows in turn are driven by socio-economic changes in farming practices and urbanization. Increases in the concentration of methane, carbon dioxide (CO2) and nitrous oxide (N2O) into the atmosphere are caused by increases in global transport, international tourism and population numbers. Together, Earth systems and socio-economic systems form a single, socio-ecological system (SES) (Ostrom, 2009), the understanding of which provides a framework for how the natural world and the actors (individuals, groups and institutions) who influence it fit together. The SES concept conceptualizes the integration of humans in nature, rather than of humans and nature. A planetary health approach should consider how multiple systems (for example, water systems for both irrigation and sanitation), fit together and also intersect with other systems (for example energy systems), that can complement one another (Fig. 1.2).

The SES is a complex adaptive system (CAS) (SRC, 2018), in which local actors interact with others to instigate the (usually gradual) emergence of small changes that slowly accumulate into large changes. The system thus displays ‘path dependency’: an event in its past determines its future development.

Adaptation and transformation

Changes in the system can be ‘adaptations’ or ‘transformations’ (Barnes et al., 2017). Adaptations are small changes that enable the system to adjust without fundamentally changing: for example, gradual coastal erosion over many decades may slowly move a community further inland as new structures are built on higher ground, but this is managed smoothly and has little obvious effect on the community or its way of living. Transformations are more fundamental changes that happen when the existing ecological, economic or social conditions make the existing system untenable. For example, severe coastal flooding may devastate a coastal town to such an extent that the community disperses; fishermen may lose their livelihoods and seek different employment elsewhere. In retrospect, a series of adaptations may look like a transformation if compared between two fixed points in time, but if the end point has been arrived at through a continuous series of small changes, the process is likely to have been much less disruptive for those living through it.

Adaptation to ecological and environmental changes enables the maintenance of existing socio-economic conditions and preserves the health and well-being of the population. The ability to adapt is, however, dependent on social capital, collaboration and cooperation. Adaptation can happen from the ground up, with little need for formal governance, or may be agreed at a more strategic level and implemented downwards through institutional rules and regulations. It tends to have low(er) financial and political costs and few(er) disadvantages to the people who are adapting.

Transformation, on the other hand, is more likely to be abrupt and to need more strategic direction (such as international or national governance). This usually invokes high(er) costs in the short term, though there may be much larger longer-term advantages. Transformation can enable a system to bounce forward into a better state, rather than bounce back to the same vulnerable conditions it was in before. It is worth bearing this distinction in mind when considering planetary health, and also the different methods by which adaptive and transformative change might be managed. Humans are the most powerful actors in SESs: we have the power to exert o...