eBook - ePub

Women's Hats, Headdresses and Hairstyles

With 453 Illustrations, Medieval to Modern

This is a test

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Women's Hats, Headdresses and Hairstyles

With 453 Illustrations, Medieval to Modern

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

From simple barbettes, crespines, and wimples worn in Anglo-Saxon times to the pillbox hat popularized by Jackie Kennedy in the mid-twentieth century, hats and headdresses have — for centuries — played an important part of a lady's wardrobe. This informative and meticulously researched book provides an authentic record of more than 1,300 years of changing fashions in women's hairstyles and headwear in England.

More than 400 of the author's own drawings — rendered from ancient sources — trace these evolving fashions. Finely detailed images depict turbans; horned, heart-shaped, and butterfly headdresses preferred by fifteenth-century English ladies; seventeenth-century hoods and veils; elaborate hats and hairstyles of the Georgian period; early Victorian-era bonnets; net and lace caps and small hats of the late nineteenth century; and the emancipated look in both hairstyles and hat styles of the early twentieth century.

The author has written a separate introduction for each historical period, placing headdresses and hairstyles in the fashionable context of their time. Pages of drawings are accompanied by detailed notes on the styles illustrated, including information on the materials used and the varying methods of manufacture. A brief glossary and bibliography add to the book's effectiveness. For those who want to get their historical details accurate, this profusely illustrated guide will be an invaluable reference.

`Designers for any media and students of history will use and enjoy the book.` (Choice).

`Remarkably entertaining.` (The Economist)

More than 400 of the author's own drawings — rendered from ancient sources — trace these evolving fashions. Finely detailed images depict turbans; horned, heart-shaped, and butterfly headdresses preferred by fifteenth-century English ladies; seventeenth-century hoods and veils; elaborate hats and hairstyles of the Georgian period; early Victorian-era bonnets; net and lace caps and small hats of the late nineteenth century; and the emancipated look in both hairstyles and hat styles of the early twentieth century.

The author has written a separate introduction for each historical period, placing headdresses and hairstyles in the fashionable context of their time. Pages of drawings are accompanied by detailed notes on the styles illustrated, including information on the materials used and the varying methods of manufacture. A brief glossary and bibliography add to the book's effectiveness. For those who want to get their historical details accurate, this profusely illustrated guide will be an invaluable reference.

`Designers for any media and students of history will use and enjoy the book.` (Choice).

`Remarkably entertaining.` (The Economist)

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Women's Hats, Headdresses and Hairstyles by Georgine de Courtais in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Fashion Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

DesignSubtopic

Fashion DesignGeorgian Part 1

1714 -1790

The eighteenth century is notable for two tendencies in the costume of both sexes, which vied with one another throughout the greater part of the period. The one was a mode of elaboration and formality, the other a taste for simplicity. The desire for a more comfortable style of clothing may have been inspired by the English love of country life and outdoor activities, a characteristic which became strongly developed during this period; or the contrast between the two styles of dress may have symbolized the struggle between traditional class distinction on the one hand and the effects of inevitable social change on the other. Whatever the reasons it was apparent that for the first time in history fashion was no longer the prerogative of the upper classes. Many features of working-class clothing were adopted by men in all walks of life, and except for Court wear and the most formal occasions this plainer style of dressing became universal. From 1760 to 1780 there was a period of exaggerated fashion and an ostentatious display of luxury which was largely the result of successful commercial activity by many in India and the West Indies. A distinction was beginning to be made between dress or best wear and undress or informal everyday wear, but this was not so apparent in women’s clothing.

Feminine dress on the whole retained an elegant simplicity throughout the period and changes were chiefly confined to the modification of existing styles or alteration in details. The most noticeable feature of the silhouette was the hooped skirt, of which there were several versions. The first style to become fashionable was the bell or dome shape which was worn from about 1710 to 1780. The fan shape appeared towards the end of Queen Anne’s reign but did not become popular until 1740. This type was flattened at the front and back so that the hem dipped to the floor and rose up at either side. The third style of hoop, which also became fashionable about 1740 was elongated, that is, extremely wide at the sides but flat at front and back. Hoops reached their widest dimensions in the 1750’s and were popular with all classes, although many working-class women wore smaller hoops or quilted petticoats instead. A unique feature of the eighteenth century was the gown with the sack back which first appeared about 1720, and in a number of variations this style remained fashionable for many years. Although the material of the working-class women’s clothing was plainer than the superb silks and satins frequently used for the dress of wealthier women the gowns themselves were in the fashionable styles of the time. In 1782 a foreign traveller noted that Englishwomen generally were so interested in clothes that even the poorest servant was careful to be in the fashion, particularly in hats and bonnets.

The low, simply dressed hairstyle which followed the sudden disappearance of the fontange at the end of Queen Anne’s reign remained unchanged for many years in spite of the obvious disparity between the small heads, with their little caps, and the great hooped skirts. It is probable that only a minority wore the exaggerated hairstyles and great wigs which were fashionable in the 1770’s, although most women appeared to follow the trend for higher styles by raising their hair over pads or rolls and by “frizzing” or back combing. A French visitor to England observed that English ladies were so conscious of their beauty that they tended to neglect their dress and “the care of dressing, that of dressing the hair above all, is observable in only a small number of ladies who . . . have resolution enough to go through all the operations of the hairdresser. The country life led by these ladies during the greater part of the year and the freedom which accompanies that way of life make them continue an agreeable negligence in dress which never gives disgust.”

Englishwomen of the late eighteenth century undoubtedly regarded their hats as the most important part of their costume and they knew how to wear them with the right air of elegance and grace.

In this century the straw plait industry expanded greatly owing to the production in Italy of a fine wheat straw which was used eventually in making the famous Leghorn plait which, because of its quality, was much sought after in England and other countries where straw hats were made. In addition to ready-made hats, straw and chip plait was imported and made up into hats and bonnets by milliners, cap makers and mantua makers. Chip, which was made from strips of willow or poplar plaited in the same way as straw was mentioned frequently throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and was used considerably as an alternative to straw. Such was the growth of the trade that separate establishments were set up to deal with the making of straw hats and, in course of time, with all types of hats worn by women. In the eighteenth century milliners dealt with the great variety of trimmings and ornaments so popular at the period and were not specifically concerned with the making of hats. It was not until well into the nineteenth century that milliners became associated with hat making and trimming exclusively.

1 Hairstyles 1714-1770

After the disappearance of the tour and the fontange in the reign of Queen Anne the hairdressing styles became relatively simple. Although forehead curls and favourites were worn by many for the first few years of George I’s reign the emphasis was tending to be towards the back of the head, where the hair was coiled into a small bun and one or two long locks hung behind or lay over the shoulders. After going out of fashion generally this style was still worn at Court.

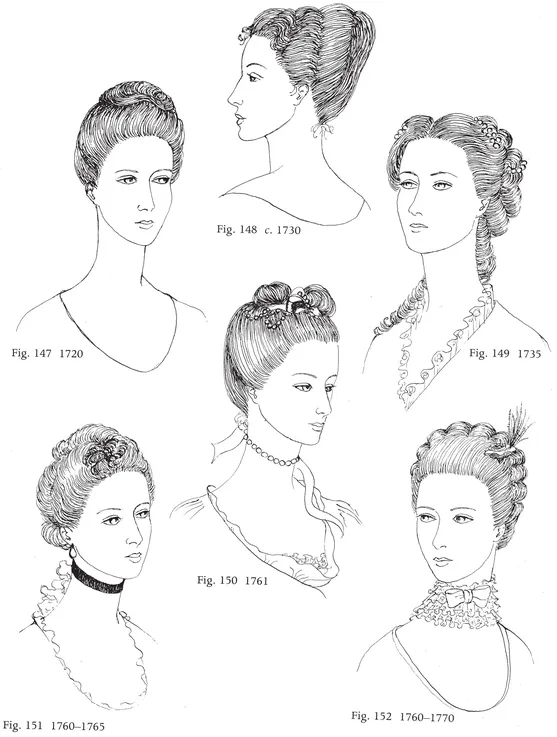

After about 1720 the majority of women of all classes preferred to wear a simple style, with the hair drawn loosely back from the forehead with a bun on top and slightly towards the back of the head. Sometimes curls were arranged round the face or stray locks allowed to fall casually about the temples (Figs 147 and 148).

This method of dressing the hair remained generally fashionable until after the middle of the century. A style which became popular in the 1730’s, especially for formal occasions was the “Dutch” coiffure (Fig. 149). The hair was drawn back from the face in loose waves, sometimes with a centre parting, and fell in ringlets or wavy locks at the back of the neck. On dress occasions no cap was worn with this style, but pearls were entwined in the hair or knots of ribbon were used as decoration.

Another style worn during the same period was a false “head” of close curls called a tête de mouton. This, together with the “Dutch” style remained fashionable for about 20 years. Topknots, bunches of ribbon loops in various colours, artificial flowers, jewels and pearls set on ribbons or pins were worn as decorations. A pom-pom set in front or slightly to the side of the head was one of the most popular hair ornaments throughout the middle years of the century. Ribbons, small feathers such as ostrich plume tips, lace flowers, butterflies and jewels in any combination went to make up this decoration (Figs 150, 151 and 152). Wigs were worn but usually only for riding or perhaps at Court.

White, grey or coloured hair powder seems to have been used by many women throughout the early part of this period, but apparently only for special occasions although its use became more and more general with the increasing elaboration of the coiffures in the 1760’s. About the middle of the decade rolls of horsehair, tow or wool began to be used to raise up the front hair, which was often frizzed or arranged in roll curls set horizontally round the head (Fig. 152), False hair and pomatum began to be used also in order to give additional height and body to the coiffure. The back hair was still turned up and arranged in a knot on top or at the back of the head. By 1770 the fashionable hair style for dress wear was quite high and large plumes were being worn.

The pomatum or paste which was used to stiffen up the hair and hold the powder was made of various substances such as hog’s grease, tallow, or a mixture of beef marrow and oil.

2 Hairstyles 1770-1780

In the 1770’s the fashionable hairstyle reached extraordinary heights and was decorated with a fantastic number and variety of ornaments. The hair was dressed over pads or cushions stuffed with wool or horsehair and all styles and shapes were built over these cushion foundations. Smaller pads and wire supports were also used. Various arrangements were popular, but an oval or egg shape, and a heart or crescent shape were the most usual. Large roll curls were placed more or less horizontally on each side of the head sometimes reaching the top, as in Fig. 154A, sometimes in small groups behind or around the ears. At least one curl generally hung vertically or horizontally behind and below the ear. The back hair was usually dressed in a chignon, a wide swathe of hair hanging down behind and then looped up and fastened with long pins or bound in the middle with ribbon (Fig. 155). The general appearance of the chignon was flat and smooth. Later the back hair might be plaited, or twisted (Figs 154B and 157). In the Lady’s Magazine for May 1775 the fashionable style for full dress was described as being “all over in small curls and pearl pins, starred leaves and large white or coloured feathers, two drop curls at the ears and powder universal”. The same magazine described the headdress illustrated in Fig. 156 as being “ushered in at the beginning of Spring with a small tuft of feathers which was soon changed to two or three distinct ones of the largest size, some pink or blue but most generally white and placed remarkably flat, with a rose of ribbons on the forepart and a knot suspended at the back of the head—with two, three or four large curls down the sides with bottom curl nearly upright. The bag (chignon) not so low as the chin, small and smooth at the bottom.”

In 1779 the London Magazine reported “the ladies dress their hair very high. They have just introduced a method of plaiting the hair behind in one row up the middle of the head on which they place large bows of ribbon” (Fig. 157). In 1778 Lady Clermont wrote to the Duchess of Devonshire from Fontainebleau: “The heads are full as high as last year, but not near so high as in England.”

The art of preparing these elaborate “heads” involved the expenditure of much time and skill and good hairdressers or friseurs were much in demand. One of these, James Stewart, who wrote a treatise on the subject, warned those ladies who wished to dress their own hair that they would find it very troublesome and tedious. “Those who are willing to surmount these difficulties, and can spare two or three hours with patience and perseverance, may in time, by practice make some progress and proficiency.”

It is not surprising that after spending several hours having the hair cut, pomaded, curled, frizzed, powdered and finally loaded with ornaments or feathers and draped with gauze or ribbons women allowed these structures to remain untouched for several weeks or even months. Stewart’s instructions were explicit: “At night all that is required is to take off cap and ornaments and nothing need to touched but the curls, do them in nice long rollers firmly. The hair should never be combed at night as this may cause violent head-aches next day. A large net fillet with strings drawn tight round face and neck, this with a fine lawn handerchief is sufficient night covering for the head.” Next day the curls were to be unpinned and the surface of the hair “raked hard” to remove loose powder, then pomading, frizzing and powdering as before. “In this manner you may proceed every day for two or three months, or as long as the lady chooses, till the hair gets straight and clotted and matted with dirty powder. Then it is absolutely necessary to comb it out.” Detailed instructions we...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman Seventh century A.D. to 1154 A.D.

- Plantagenet - 1154–1399

- Lancaster 1399 -1461 - York 1461-1485

- Tudor - 1485 -1558

- Elizabethan - 1558 -1603

- Stuart - 1603-1714

- Georgian Part 1 - 1714 -1790

- Georgian Part 2 - 1790–1837

- Early Victorian - 1837-1860

- Mid-Victorian - 1860-1880

- The Late Victorian Period - 1880–1901

- Twentieth Century - 1914 -1985

- Headwear of domestic servants and nurses

- Bridal headdress

- Glossary

- Sources of Information

- Bibliography

- Index