This is a test

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Building of Manhattan

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Meticulously accurate line drawings and fascinating text trace Manhattan's growth from a tiny Dutch outpost to the commercial, financial, and cultural heart of the world. This book explains construction above and below ground, including the excavation of subway lines and the building of bridges and skyscrapers. Hundreds of illustrations reveal intricate details of construction techniques.

Author and illustrator Donald A. Mackay traces Manhattan's history from its first wood, stone, and brick houses to its famous modern structures, including the Empire State Building, Rockefeller Center, and the World Trade Center. Along with historical background, he presents clear explanations and illustrations of the skilled labor and methods behind the island's tunnels, bridges, and train lines. Mackay describes who does what at a construction site, the assembly of a tower crane, and the construction of skyscrapers, from the foundations to the floor-by-floor elevations, along with other amazing procedures that are all part of a day's work in building the big city. A selection of the Common Core State Standards Initiative.

Author and illustrator Donald A. Mackay traces Manhattan's history from its first wood, stone, and brick houses to its famous modern structures, including the Empire State Building, Rockefeller Center, and the World Trade Center. Along with historical background, he presents clear explanations and illustrations of the skilled labor and methods behind the island's tunnels, bridges, and train lines. Mackay describes who does what at a construction site, the assembly of a tower crane, and the construction of skyscrapers, from the foundations to the floor-by-floor elevations, along with other amazing procedures that are all part of a day's work in building the big city. A selection of the Common Core State Standards Initiative.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Building of Manhattan by Donald A. Mackay, Donald A. Mackay in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & History of Architecture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

History of ArchitectureTHE RIVETER: $1.92 PLUS HALF A CENT AN HOUR

The putting together of the open steel framework of the Empire State Building revealed one distinct difference from the framework of the skyscrapers being put up today.

It was full of rivets.

And its construction was audibly different from today’s methods of building.

Riveting made such an infernal racket that New Yorkers wrote angry letters to the newspapers about the noise.

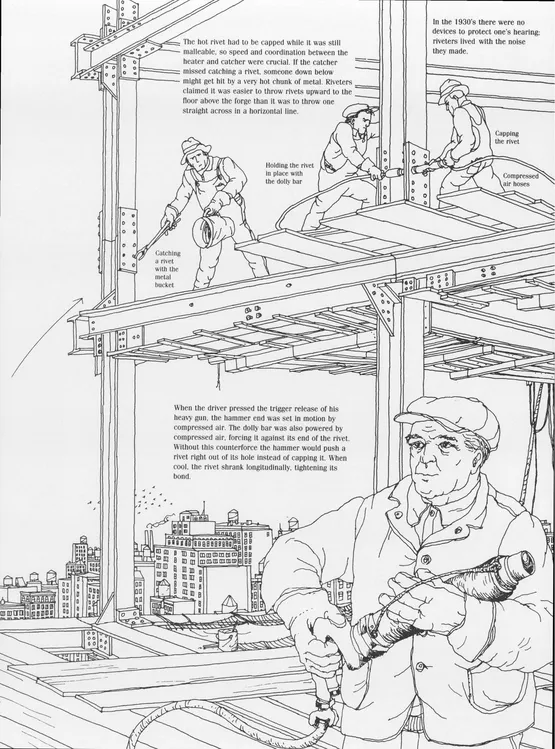

A test had already shown that welded joints were stronger than riveted joints in construction. But, in the 1930’s, the riveting gang was still the center of activity in the building of skyscrapers. What they did held everything in place.

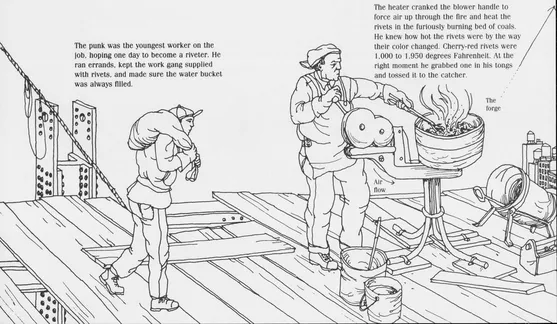

There were four men in a riveting gang. According to a news report of that time, they were called the “heater,” the “catcher” or “sticker,” the “bucker-up,” and the “driver” or “riveter.” There was also the young helper, or “punk.”

The heater cranked the handle of his forge, forcing air up through the coke or charcoal fire, making it flaming hot and heating to an incandescent glow the 10 or more rivet bolts buried in the fire.

When the driver was ready for a new rivet, the heater took a hot cherry-red one out of his forge with his long-handled tongs. And with an underhand toss he hurled the smoking rivet straight at the catcher, who caught it in mid-air in his catching can. The catcher then grabbed it with his tongs, tapped it against a beam to remove any cinders, and jammed it into the waiting hole.

The bucker-up held the rivet in place with his heavy steel dolly bar while, facing him on the opposite side of the pieces being riveted together, the driver pressed the release on his hammer. Within seconds, and with a chattering outburst of noise, his end of the rivet was smashed into a wide cap, permanently bonding together two more sections of the skyscraper framework.

Today, the steel beams and girders of the city’s skyscrapers are bolted together with special steel bolts and welded together. Compared with riveting, these connections are stronger, more quickly made, and require fewer men to accomplish.

At the peak of construction on the Empire State Building there were thirty-eight riveting gangs working from 8:30 A.M. to 4:30 P.M.—with half an hour off for lunch. The number of rivets set in place in a day depended on the size of the rivets, and whether the crew was straddling a cold steel beam with nothing much below them or working inside the protection of the building itself. A fast crew might set up to 800 rivets a day. Union scale for riveters was $1.92, plus half a cent, per hour, with double pay for overtime.

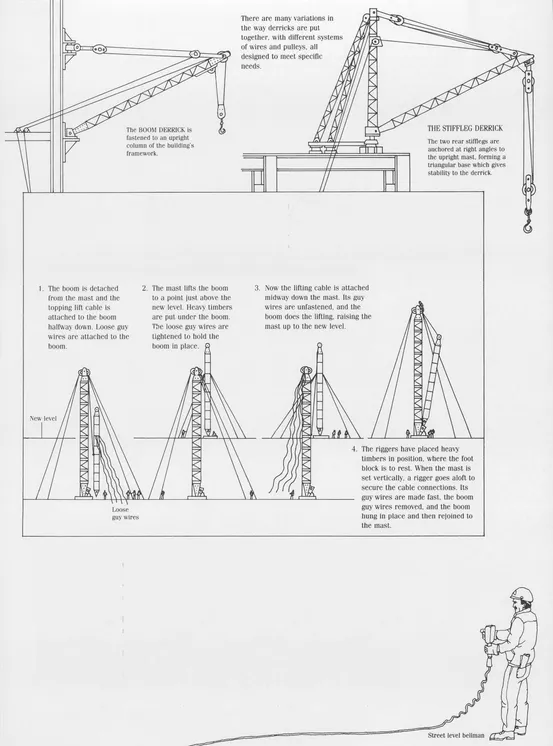

THE DERRICK

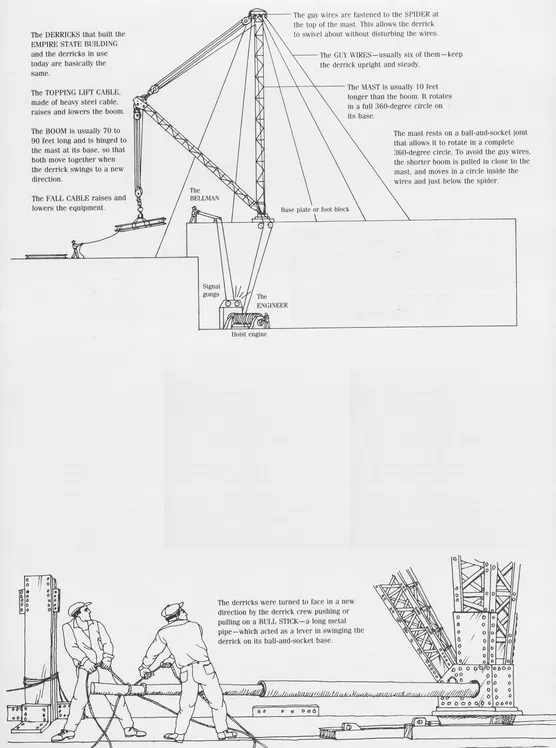

There were as many as sixteen derricks working on the Empire State Building at the same time. Their size and lifting abilities varied, from those limited to a 20-ton load to the biggest—capable of lifting the heaviest load needed, 44 tons.

Wherever possible, the derricks were positioned so that their booms overlapped, allowing material to be placed exactly where needed.

As construction proceeded and the derricks were raised to ever-increasing heights, their cables had to be lengthened to reach the hoist engines down below them. Holes were left in the newly poured concrete floors so the cables would have the most direct link between the hoist engines and the derricks.

The biggest hoist engines were ultimately placed on the 25th floor and the smaller ones on the 52nd floor, where the setbacks in the building’s design made it desirable to do so. At the greatest heights, the derricks had to raise the steel beams and columns in two separate liftings—changing over at the 25th floor.

Today the hoisting, the lowering, and the transfer of loads horizontally may still be done by derrick. The derrick is controlled by an operating engineer who is usually at a lower level of construction and doesn’t see the actual loading or unloading of the tons of material he is moving about. In operating his controls, the engineer depends on signals from his loading and unloading bellmen.

During construction of the Empire State Building the bellman pulled on two cables, each attached to a separate bell next to the derrick engineer, who adjusted his winch cables according to the bells.

Today the engineer gets his signals from a bellman pressing buttons on a portable bell box which connects to, and activates, bells and lights at the hoist engine. The bells tell the engineer the function: to raise or lower the boom. The light signal, steady or flickering, is the speed of the function. When raising steel from a delivery truck to the top of an unfinished building, a bellman at street level will give the signals until the steel reaches the top; then a bellman on top takes over. The hoist engineer is located at a lower level, probably in a walled-off enclosure, and cannot see the derrick or the bellman.

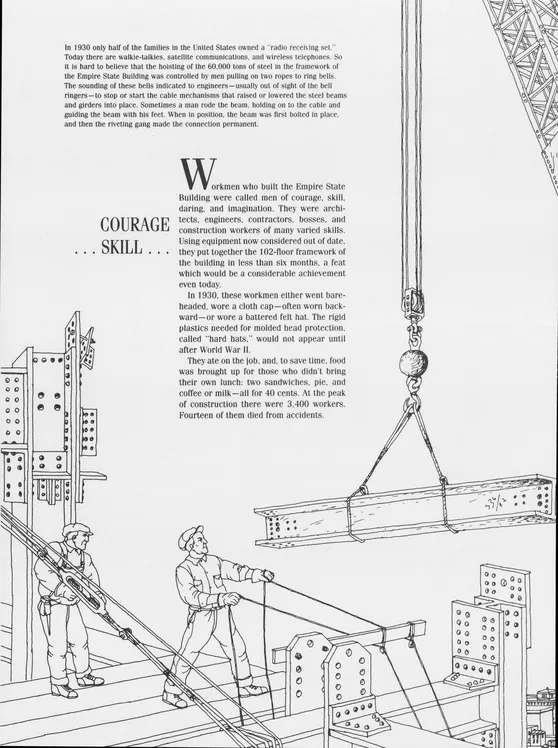

COURAGE . . . SKILL . . .

Workmen who built the Empire State Building were called men of courage, skill, daring, and imagination. They were architects, engineers, contractors, bosses, and construction workers of many varied skills. Using equipment now considered out of date, they put together the 102-floor framework of the building in less than six months, a feat which would be a considerable achievement even today.

In 1930, these workmen either went bareheaded, wore a cloth cap—often worn back-ward—or wore a battered felt hat. The rigid plastics needed for molded head protection, called “hard hats,” would not appear until after World War II.

They ate on the job, and, to save time, food was brought up for those who didn’t bring their own lunch: two sandwiches, pie, and coffee or milk—all for 40 cents. At the peak of construction there were 3,400 workers. Fourteen of them died from accidents.

. . . AND PREPARATION

Careful, detailed planning and much paperwork enabled the Empire State Building to be put up in record time.

A progress chart and a printed timetable were issued daily. These specified everything to be done that day, identifying each truck that would drive right in onto the first floor, what it would be delivering, and who was responsible to receive it and to use the materials it carried. Each steel piece was numbered to see that it went to the proper derrick and to indicate its proper place in the building. The other materials—75 miles of water pipe, 10 million bricks, 1,172 miles of wire for elevator cable, 50 miles of radiator pipe, more than 6,000 windows, 2 million feet of electrical wire, and 200,000 cubic feet of stone—went up by derrick sling or by elevator directly to the floor where it was scheduled to be used. A temporary, small narrow-gauge track system was installed on each floor as it was needed. This enabled the material to be moved from the truck at ground level onto dump carts, raised by elevator to the designated floor, wheeled onto the track, and moved quickly to the exact spot needed. Turntables built into the track allowed the carts to be shifted about in any direction.

The scheduling, organization, and attention to detail that characterized the building of the Empire State Building is part of skyscraper history.

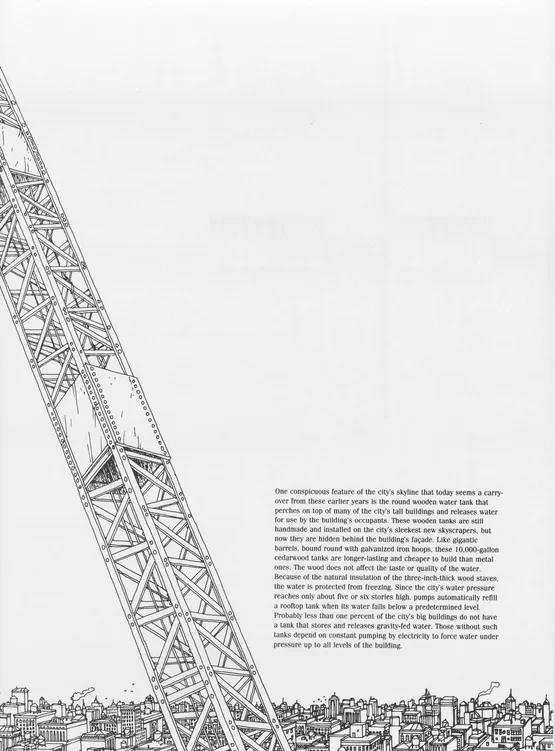

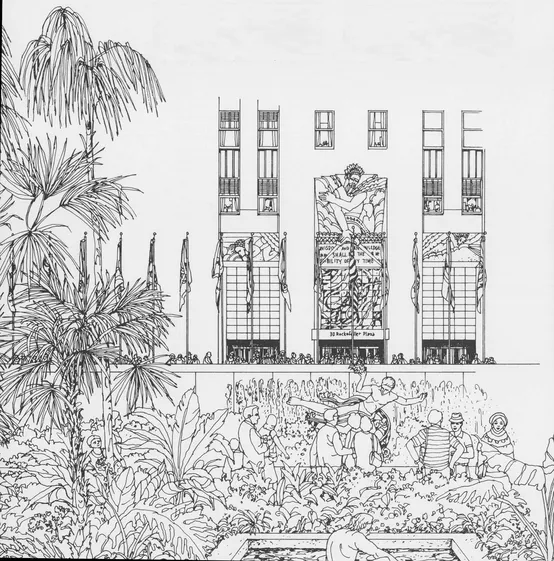

MIDTOWN MANHATTAN . . . ROCKEFELLER CENTER: 1931

Rockefeller Center is a wonderful place for people-watching. Its Fifth Avenue promenade—the Channel Gardens—and its sunken plaza invite visitor and New Yorker alike to enter, slow down, rest awhile, breathe a bit more easily, and enjoy the visual variety. People from all over the world stop by, carrying cameras. They take pictures of golden Prometheus and his backdrop of cascading water; they take pictures of each other.

They are in a horticultural oasis—unique in the city—where imported exotic greenery changes as the seasons change. Where else would palm trees flourish just off Fifth Avenue ... or a Christmas tree weighing several tons suddenly appear to signal the beginning of the city’s holiday season?

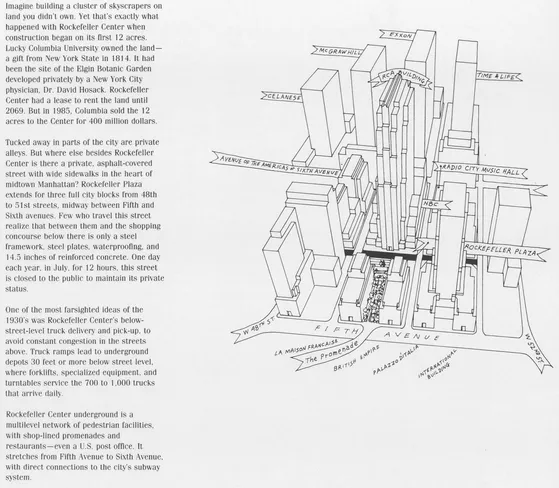

Planned as an integrated complex of buildings for business and entertainment, Rockefeller Center has been expanded since its inception in 1931. Today it has eighteen skyscrapers built about its central skyscraper—the 70-story RCA Building—and it covers almost 22 acres of land in the heart of Manhattan.

Its planners envisioned the site with each skyscraper a unit in relation to each of the other skyscrapers, and to the Center itself. They planned for landscaped areas of open “city space” for light and air, with interconnected patterns of traffic flow, both pedestrian and vehicular, for ease of movement. This design concept was, in 1931, unique for its time, and Rockefeller Center has become a model for similar projects around the world.

The land on which a large part of the Center is built had already been leased in 1928, to be built upon by private builders. Then came the worldwide depression that began with the 1929 stock-market crash, and any idea of building was abandoned. Millions of people were out of work, and most large-scale construction in New York City—with the exception of the Empire State Building—had stopped. It was a time of despair and of caution. Yet, faced with a costly yearly lease, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., decided to develop the site, personally, as a private enterprise.

In human terms it was an enormous project. Two hundred twenty-eight delapidated tenements, shops, and other buildings had to be demolished and carted away. Four thousand tenants had to be relocated in new living and working quarters.

At a time of vast unemployment, at least 75,000 people were employed at the site, and 150,000 others worked elsewhere, preparing the materials used in the construction.

Rockefeller Center was a civic enterprise on a major scale, as well as a construction project of enormous size.

Its open spaces—nearly one-fourth of the land space has been left unbuilt—with promenades, plazas, trees, flowers, and sculpture, and the lower plaza with its ice-skating rink in winter and outdoor dining in summer, make the Center a focal point in midtown Manhattan. Nearly a quarter of a million people use, or visit, Rockefeller Center daily. ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- IN THE BEGINNING

- THE MANHATTAN INDIANS

- AND THEN THE DUTCH CAME

- WOOD, STONE, AND BRICK

- FORT AMSTERDAM

- STUYVESANT SURRENDERS

- 1664: NEW AMSTERDAM IS NOW NEW YORK

- COLONIAL NEW YORK: 1664-1783

- MECHANICKS, SLAVES, AND APPRENTICES

- CAPITAL OF THE NEW NATION: 1785-1790

- 1811: A PLAN FOR GROWTH

- POPULATION PRESSURES: 1811—1850

- THE CAST-IRON BUILDING

- THE “SAFETY HOISTER” RAISES THE ROOF

- THE WONDER OF THE IMAGINATION

- THE SKILL OF THE ENGINEER

- THE IRON SKELETON

- “AN IRON BRIDGE TRUSS STOOD ON END”

- 1850 TO 1900

- THE FLATIRON BUILDING: 1901

- THE WOOLWORTH BUILDING: 1913

- BOOM AND BUST: 1900—1930

- THE EMPIRE STATE BUILDING: 1930— 1931

- THE RIVETER: $1.92 PLUS HALF A CENT AN HOUR

- THE DERRICK

- COURAGE . . . SKILL . . .

- . . . AND PREPARATION

- MIDTOWN MANHATTAN . . . ROCKEFELLER CENTER: 1931

- OUT OF THE DEPRESSION: 1930—1965

- DOWNTOWN MANHATTAN . . . THE WORLD TRADE CENTER: 1966—1971

- KEEPING THE HUDSON RIVER OUT

- A PROBLEM IN LEVITATION

- CARRYING THE WEIGHT

- A CITY WITHIN THE CITY

- ZONING: AN ATTEMPT TO SET RATIONAL LIMITS

- THE ARCHITECT: CONCEPT AND DETAIL

- THE CITY’S VITAL SERVICES

- THE BUSY UNDERGROUND

- THE SUBWAY

- WATER FIT TO DRINK

- ELECTRICITY . . . LIFELINE OF THE CITY

- STEAM

- GAS

- TELEPHONE

- AND EMPIRE CITY SUBWAY

- SEWAGE

- GOING . . . GOING . . .

- . . . GONE

- TEST BORINGS

- AND DRILLING ROCK

- THE POWER OF COMPRESSED AIR

- THE EXCAVATORS

- DYNAMITE!

- STAND CLEAR!

- HARD HATS

- WHO DOES WHAT AT A CONSTRUCTION SITE

- THE SURVEYOR

- SHORING UP THE OUTER WALLS

- THE FOUNDATION

- DIGGING IN LOWER MANHATTAN

- BULL’S LIVER AND OTHER PROBLEMS

- AS THE CITY BUILDS

- CONCRETE

- THE REINFORCED CONCRETE SKYSCRAPER

- FROM LIQUID MASS TO HARDENED SOLID

- SALAMANDERS

- THE BIG CRANES

- TOWER CRANES

- ASSEMBLING A TOWER CRANE

- RAISING THE CRANE’S HEIGHT

- PRIVATE PLACES PUBLIC SPACES

- STEEL

- STEEL

- AND IRONWORKERS

- LOOK OUT BELOW!

- SPUD WRENCHES

- FROM BEAM

- TO BEAM

- THE WELDER

- THE FLOORS TAKE SHAPE

- THE OUTER SKIN

- TRADES AND UNIONS

- UP AND DOWN . . . AT 20 MILES AN HOUR

- SKYSCRAPER STRESS

- ACROPHOBIA ... FEAR OF HEIGHTS

- THE SOUNDS OF THE CITY

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- SOURCES