![]()

CHAPTER 1

“The language of the heart”

Genre Instruction in Heteronormative Relations

Had letters been known at the beginning of the world, epistolary writing would have been as old as love and friendship; for, as soon as they began to flourish, the verbal messenger was dropped, the language of the heart was committed to characters that faithfully preserved it, secresy was maintained, and social intercourse rendered more free and pleasant.

The Fashionable American Letter Writer (1832)

Nineteenth-century people seeking to learn romantic epistolary rhetoric could consult a wide range of texts. They could learn from periodical articles, such as the already discussed Godey’s Lady’s Book piece about Eliza’s love letters (Leslie, “Part the First,” “Part the Second).1 People could learn from literary texts that represented epistolary exchange, including not only epistolary novels but also sentimental literature and slave narratives.2 Also available to learners were models of epistolary rhetoric in the published letters of literary and political figures, as well as the more ordinary letters read aloud and shared within familial circles.3 While less explicitly pedagogical than letter-writing manuals, all of these texts offered lessons about the potential relational consequences of composing letters. Moreover, in terms of overtly pedagogical texts, single chapters about epistolary rhetoric were included within instructional manuals of different types: rhetoric and composition textbooks assigned in schools and colleges, as well as universal instructor manuals and conduct and etiquette guides designed for home use.4

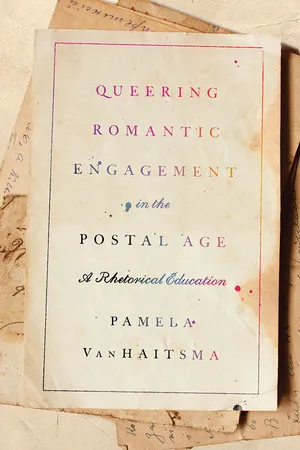

But the most extensive instruction in specifically romantic epistolary rhetoric was provided through popular manuals that focused entirely on letter writing. Often called “complete letter writers,” these manuals devoted entire chapters to the romantic subgenre, or what The Fashionable American Letter Writer (1832) calls “the language of the heart” (iii). While complete letter writers constitute just one strand of a rich epistolary culture ripe with opportunities for learning romantic epistolary practices, my archival research focuses on these manuals because of their popularity. Widely available and intended for home use, the manuals amounted to what Anne Ruggles Gere has termed an “extracurriculum” of rhetorical instruction, which “extends beyond the academy to encompass the multiple contexts in which persons seek to improve their own writing; it includes more diversity in gender, race, and class among writers” (80).5 Popular letter-writing manuals reached more diverse audiences of adult learners, including those with little access to schooling and especially to formal college-level training in rhetoric, than did college and university textbooks.

After further introducing the features of complete letter writers as sites of rhetorical education for romantic engagement, my analysis asks how these manuals taught language practices for composing romantic epistolary rhetoric and, by extension, cultural norms for participating in romantic relations. While manuals advised simply writing “from the heart,” they extensively modeled the genre conventions constraining such composition. In modeling conventions for the romantic subgenre of the letter, manuals embedded a heteronormative conception of romantic relations. At the same time, however, manual instruction emphasized rhetorical strategies of invention through copying and adaptation, which rendered the same model letters susceptible to more queer effects and failures.

COMPLETE LETTER WRITERS

Letter-writing manuals in the nineteenth-century United States continued a long rhetorical tradition, detailed in Carol Poster and Linda C. Mitchell’s Letter-Writing Manuals and Instruction from Antiquity to the Present. In the West this rhetorical tradition may be traced from Cicero to the medieval ars dictaminis, from Erasmus to seventeenth- and especially eighteenth-century British manuals.6 Two features of the tradition were carried forward in nineteenth-century manuals with significant implications for their instruction in romantic epistolary rhetoric. First and foremost, the letter continued to be defined in ways consistent across Western rhetorical history. Cicero defined the letter as “written conversation,” Erasmus as “a conversation,” and Blair as “conversation carried on upon paper.”7 Cicero’s definition was rehearsed across late seventeenth- to early nineteenth-century British and U.S. manuals. Second, in keeping with this definition, manual instruction was marked by what Eve Tavor Bannet called a “paradox”: between the commonplace, even clichéd, instruction to compose letters simply by writing as though one would speak to the audience and the existence of manuals offering elaborate recommendations and models teaching how to do so—not so simply after all, as the story of Eliza’s love letters suggests when she wishes for such a manual (53, 276). As I discuss, this pedagogical paradox of letter-writing manuals and definition of the letter played out in particular ways within nineteenth-century instruction in the so-called language of the heart.

My analysis of such instruction is based on archival study of letter-writing manuals in the University of Pittsburgh’s Nietz Collection. One of the largest of its kind, the Nietz Collection consists of about nineteen thousand textbooks from the United States, including nineteenth-century letter-writing manuals as well as etiquette guides with sections on letter writing. While I reference etiquette guides containing instructions consistent with popular letter-writing manuals, my analysis focuses on the latter.8 I concentrate especially on the most popular type of extracurricular letter-writing manual, the “complete letter writer.” Books with variations of the title Complete Letter-Writer have been republished countless times in the United States since at least 1790. These “complete letter writers,” like their eighteenth-century English predecessors, were named for their inclusion of a wide range of model letters, often hundreds of them, and related claims to assist with every situation in which any person might write a letter (Bannet 22). In the words of Henry Loomis’s manual Practical Letter Writing (1897), “Complete letter-writers are books giving model letters, so-called, on all subjects” (67). Whether or not a manual was titled Complete Letter-Writer, the book was understood as such if it attempted completeness through the provision of model letters.

The contents of complete letter writers were structured in keeping with their objective to provide models “on all subjects” (Loomis 67). The Fashionable American Letter Writer exemplifies the characteristic organization of manual contents. The manual begins with a “Preface” emphasizing the importance of epistolary rhetoric (iii–iv). Its “Introduction,” while including instruction in principles of spelling, grammar, punctuation, handwriting, letter folding, and style, claims that the best way to study epistolary rhetoric is through “fair examples” and “specimens” that illustrate those principles (xiii–xx). Another section, “Directions for Letter-Writing, and Rules for Composition,” actually says nothing of letter writing in particular but instead offers more general instruction in rhetorical principles and style (xxi–xxxii). Following these short initial sections, or chapters, the manual consists mainly of model letters. The models are divided into chapters titled “On Business,” “On Relationship,” “On Friendship,” and “On Love, Courtship, and Marriage.” The titles of the multiple models within these chapters are listed above each model as well as in the manual’s table of contents. To varying degrees, the contents of most complete letter writers were organized similarly: manuals opened with a relatively brief introduction to principles of rhetoric and writing in general and/or epistolary rhetoric in particular. The rest of the manuals consisted primarily of model letters. These models were organized by subgenre and labeled with titles suggestive of variations within each subgenre, in terms of the specific rhetor, audience, and purpose.

The characteristic contents and organization of complete letter writers leave no question that their instruction in letter writing was a form of rhetorical education, even if distinct from formal college-level training. Manual instruction amounted to rhetorical education because it treated language and meaning as produced, understood, and negotiated in ways inseparable from rhetorical situations involving rhetor, audience, purpose, and the larger social context. As complete letter writers filled the majority of their pages with titled model letters, the features of rhetorical situations were marked over and over again, on page after page. In The Fashionable American Letter Writer, for instance, pages 39 to 179 present nothing but model letters. Sample titles for these models include “From a Tenant to a Landlord, excusing delay of Payment” (45), “From a young Woman, just gone to service in Boston, to her Mother in the country” (110), and “From a Gentleman to a young Lady of a superior fortune” (62). As such, readers could learn to become rhetorically minded as they found one example after another, for well over a hundred pages, of models that called attention to the audience being addressed in the salutation, the rhetorical purpose articulated in the initial lines of the letter, and the rhetor signing the letter.

While structured much like their English predecessors, “American” complete letter writers sought to distinguish their models as fitting for the rhetorical situations distinctive of “an enlightened and educated country like the United States” (Shields 15).9 These manuals marked their model letters as not “English” but “American,” not “savage” but “civilized.” In one troubling but perhaps expected instance, Frost’s Original Letter-Writer (1867) acknowledges the widespread practice of letter writing in “every country” but differentiates the practices of “the savage” from those “marked” by “the progress of civilization.” Frost’s even describes this “progress” through a narrative about the colonization of “the rough Western wilds” (Shields 14). The preface to The Complete American Letter-Writer (1807) insists that, because it is addressed to “this country” and what is “important in the life of a young American,” its models “are not taken from the English books of forms” (iii). The Complete Art of Polite Correspondence (1857) claims that its “letters are all carefully adapted to the circumstances of our own country, and a considerable number are taken from approved American writers” (10).

In keeping with this emphasis on “American” letters, manuals also left no question that they modeled culturally specific social relations as much as epistolary rhetoric. Social markers listed in model letter titles explicitly called attention to the ways that rhetors and audiences were positioned by class, age, family, gender, education, and region (as well as race, in a few instances). Moreover, the organization of the models by subgenre emphasized what Carolyn Miller referred to as each subgenre’s “recurrent situation” and, within that situation, “typified rhetorical action” and “conventionalized social purpose” (162). In short, complete letter writers modeled social conventions for who was to write what to whom, with what purposes, and within which situations. They offered, in the words of Elizabeth Hewitt, “a veritable how-to manual for depicting and enforcing appropriate social relations” in the nineteenth-century United States. (11).

Before turning to my focus on the heteronormative dimensions of these “appropriate social relations,” I want to acknowledge how this epistolary instruction in gender and sexuality intersected with normative ideas about class and race. Class was central to the culturally approved romantic relations modeled by complete letter-writer manuals. Manuals marked class with model letter titles that distinguished between the epistolary rhetoric of a “servant,” a “woman,” and a “lady”—and between the epistolary rhetoric of a “tradesman,” a “man,” and a “gentleman.”10 These titles suggested the genre’s potential, however limited, to enable romantic address across at least some class differences. The Complete Letter Writer (1811) includes a “Letter from a young Tradesman to a Gentleman, desiring Permission to visit his Daughter,” and then a “Letter from the same to the young Lady, by permission of the Father,” indicating that this particular cross-class romantic relation was culturally sanctioned through the patriarchal structure of the family. Other models instructed learners against participation in cross-class epistolary rhetoric. The Fashionable American Letter Writer, for instance, contains a letter “From a rich young gentleman to a beautiful young lady without a fortune,” to which the lady responds, “You know that I have no fortune; and were I to accept your offer, it would lay me under such obligations as must destroy my liberty,” concluding, “let me beg, that you will endeavor to eradicate a passion, which if nourished longer, may prove fatal to us both” (79–82). Through model exchanges like these, readers were taught what sorts of cross-class romantic relationships to pursue or avoid through romantic epistolary rhetoric.

Whereas complete letter writers marked class distinctions explicitly, racial categories were rarely noted. Instead, manuals taught romantic relations as racialized, though less obviously so, in the silent way that renders whiteness as an unremarkable norm. As Julian Carter wrote in his study of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century sex advice manuals, “one of the hallmarks of … ‘normal whiteness’ … was the ability to construct and teach white racial meanings without appearing to do so” (2).11 Given the relative absence of racial markers in most letter-writing manuals, it is likely that model letters were understood as written by and addressed to white people of various genders and classes but that whiteness was privileged to the point of being taken for granted, that “American” was taken to mean “white.” This reading of unmarked race as whiteness is confirmed by the few mentions within guides of racial or ethnic markers other than “American.” For example, The Parlour Letter-Writer mentions “the Irish laborer who … writes … to his kinsfolks across the wide ocean,” as well as letters to and from an “English gentleman” (Turner xiii–xv, 116). The Pocket Letter Writer includes a model marking blackness—“From a colored laboring man to a gentleman, soliciting a situation for his son”—though this letter does not model romantic epistolary rhetoric (xviii). Thus it is highly probable that, with marked exceptions, manuals offered instruction in epistolary rhetoric designed for those presumed to be white “Americans.”

Not surprisingly, given the ways complete letter writers modeled social relations, historians of rhetorical education as well as cultural historians have studied how manual instruction in epistolary rhetoric taught the cultural norms governing social relations. In the most developed line of inquiry, already discussed, feminist historians of rhetoric have explored questions about gender and genre. Jane Donawerth, Nan Johnson, and Deirdre M. Mahoney investigated whether and how instruction in the epistolary genre enabled or constrained women’s rhetorical practices and participation in civic life. In other studies, Mary Anne Trasciatti explored how bilingual, bicultural manuals modeled U.S. norms for social and business life to Italian immigrants. Bannet examined how complete letter writers appealed to readers across class lines but inscribed differences between social classes. And Lucille M. Schultz studied how school-based textbooks inculcated children in dominant cultural norms for upper-middle-class morals and manners.

Even as scholars have considered this range of questions about how complete letter writers taught cultural norms for social relations, there has been no extended attention focused on instruction in the romantic subgenre.12 Complete letter writers are ripe for an in-depth analysis of how they scripted model relations through their instruction in romantic epistolary rhetoric. Especially in separating sections on the romantic subgenre from the others, manuals modeled what was distinctive about the conventions for composing social relations through romantic letters. Analysis of this manual pedagogy is needed in order to more fully understand what Arthur Walzer characterized as rhetoric’s “complete art for shaping students,” because the “politically appropriate subjectivity” taught by rhetorical education includes the enactment of heteronormative romantic relations (“Rhetoric” 124).

GENRE CONVENTIONS IN HETERONORMATIVE MODELS

Rhetorical education through complete letter writers amounted to more than instruction in genre conventions; it functioned as instruction in model romantic relations. Manuals taught not just genre conventions for achieving one’s “own” romantic ends but what romantic “ends [one] may have” (C. Miller 165). I argue that manuals taught heteronormative ends for romantic epistolary rhetoric. Instruction in genre conventions for epistolary address taught normatively gendered romantic coupling, instruction in conventions for the pacing of exchange taught normative restraint, and instruction in conventions for rhetorical purpose taught a normative marriage telos.13 Importantly, however, manual instruction in the romantic letter reflected the broader paradox discussed earlier: in spite of extensive modeling in conventions for the romantic subgenre, manuals claimed that writing a romantic letter, like composing any other, was a matter of speaking on paper and, in the case of the romantic subgenre, doing so “from the heart.”

Romantic Letters and Writing from the Heart

The most basic instruction for the romantic subgenre of epistolary rhetoric was to write “from the heart.” In keeping with The Fashionable American Letter Writer’s designation “the language of the heart,” comple...