![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Indian Red

First, in the distance, you hear the beat of approaching drums. Then come the layers of call-and-response singing accompanied by the jangling of tambourines. An Indian flashes by, feathers rippling, the top of his headdress, or crown, projecting plumes that hover seven feet in the air. Soon you’re caught up and carried by a sudden flow of people, in the thick of it, moving with the crowd, lost in the spirit of the moment. Your sense of time is changing in this electric event, your eyes dazzled by color as Indians go past in this public gathering of people singing and dancing in the street together. It is a joyous assault on the senses. While every public ceremony in New Orleans tends to have a unique texture, the most strikingly different—the one that involves the deepest sense of connection between the ancient past and the living present—is the experience of the Mardi Gras Indians.

The term “Mardi Gras Indians” applies to groups of contemporary African Americans in New Orleans who make elaborate costumes annually for Carnival, or Mardi Gras Day (Fat Tuesday), when they take to the streets and search out other Indian tribes or “gangs” in similar attire. Among other things, the point of the search is to compete aesthetically with other Indians to see who is “the prettiest.” But this is no mere costume contest. Instead, for the participants, it is just one of a complex web of activities including sewing, dancing, drumming, engaging in public processions and private rituals—as well as special structural elements such as phrases, songs, a distinct social hierarchy and spirituality—all of which is more accurately described as a cultural system. Being an Indian means gathering all these strands of tradition and responding creatively in a complex, interwoven combination of inherited and improvised actions. It requires committing oneself to a collective identity with its own priorities, beliefs, and dynamic social order. Despite the public displays for which they are best known, Mardi Gras Indians form a community that is exclusive and even secretive.

Jay Williams, Spy Boy with the Buffalo Hunters, races down Third Street in search of other Indians on Mardi Gras 2013. Photo by John McCusker/New Orleans Advocate.

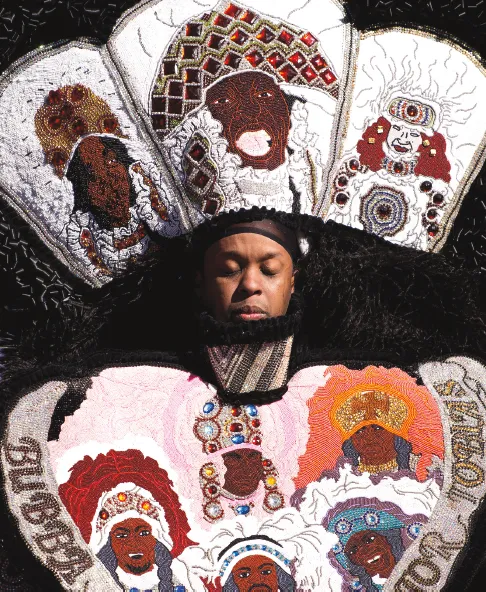

Big Chief Bo Dollis Jr. closes his eyes for a moment before crying out “Madi cu defio,” the opening line of “Indian Red,” the prayer song that the Indians sing before taking to the streets in search of other Indians, in 2016. Dollis leads the Wild Magnolias as his father did for decades. Photo by John McCusker/New Orleans Advocate.

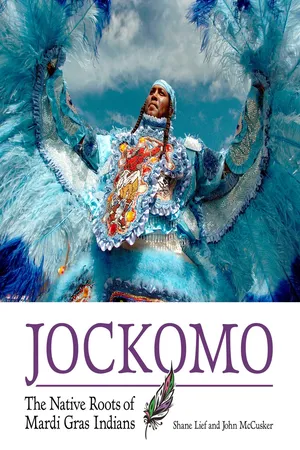

Gang Flag Thomas Watson spreads his wings as he and the rest of the Golden Blades take to the streets on Mardi Gras 2006, the first carnival after Hurricane Katrina. The Golden Blades had numerous members displaced by Katrina. Some sewed in evacuation cities like Atlanta, Memphis, Dallas, and Houston and showed up Mardi Gras morning to reclaim their place. Photo by John McCusker/The Times-Picayune.

Like the braided streams that flow to form the Mississippi River, where different groups of people have gathered to dance and sing for centuries, this culture arose from a series of blended traditions. Three hundred years ago, people from three major parts of the Earth—Africa, Europe, and North America—all found themselves in the place that has become New Orleans. This story is about recovering and remembering those who have come before us, taking up the various threads of memory and experience of different individuals and cultural groups, so we can have a greater understanding and appreciation for the people who have had a hand in creating the intricate costumes, the complex ceremonies, and the music that flows in the public spaces of the city on Mardi Gras.

Second Chief Irving Scott, of the Golden Comanche, brings his game face to Dryades Street on Mardi Gras 2006. Photo by John McCusker.

Tribes face off on Super Sunday, uptown, 1997. Photo by John McCusker.

Big Chief Irving Scott of the Buffalo Hunters opens up the crowd on Dryades Street as his group travels through uptown in 2013. Photo by John McCusker.

Walter Sandifer, right, First Spy Boy of the Creole Wild West, turns away Timothy Washington as he makes his way down Jackson Avenue on Mardi Gras 2011. Photo by John McCusker/The Times-Picayune.

Ryan Goodman of the Flaming Arrows takes to the streets in the Eighth Ward, 1997. Photo by John McCusker/The Times-Picayune.

The Cheyenne occupy Second Street with a dozen Indians in matching feathers in 2011. Photo by John McCusker.

Spy Boy Dow Edwards of the Mohawk Hunters emerges onto Amelia Street near Magazine on St. Joseph’s Night in 2013. Photo by John McCusker.

The Indian tradition is sometimes described as New Orleans culture at its most African, and this is a theme that has attracted much attention.1 Of course, it deserves further exploration. However, another path of inquiry, substantially less traveled in popular and academic literature, involves exploring how much of Mardi Gras Indian cultural tradition, on the one hand, reflects Native American legacies, and on the other, how much of it represents the projection of the “American Indian” icon. From what inspirational wells did the earliest Mardi Gras Indians draw for their music, language, dancing, sewing, and other practices?

But first, a snapshot of the Indians today.

Michael Green emerges onto Jackson Avenue and declares to the assembled crowd, “I’m a Flag Boy, Creole Wild West!” He is wearing a bright magenta suit of ostrich plumes and a single chest patch depicting an Indian man holding his bride. He carries a Mirabeau-lined cutout of a rifle that served as his flag staff that reads “Flag Boy, CWW.” His moccasins are each topped with the face of an Indian. A big man over six feet tall, his imposing presence is made more striking by the immense Indian suit as he moves through the carnival throng.

Inside, Big Chief Howard Miller is preparing to sojourn the streets that the Creole Wild West have followed for over a century. It is a process of spiritual immersion. “The transformation is coming long before that morning. It starts from sewing. Once you put it [the suit] on and the spirits should be coming into you. Guys who truly sew with their heart and soul and the right intentions I guarantee you they will tell you. Such a feeling coming over you as you pull it on. Now you’re who you’re supposed to be. It’s the spirit. How powerful is my spirit? Is it strong enough to lift these people and now can lift my tribe? And now we can go,” Miller said.2

That same morning a few blocks away, the Cheyenne take to the streets of Central City with a dozen Indians in matching gray, pink, and burgundy feathers led by Big Chief Al Womble. As each tribe emerges, they gather to sing their prayer song, “Indian Red.” The song begins with three strikes on the tambourine followed by the lone voice of the Big Chief crying out: “Madi cu defio.” The tribe responds, “En dans dey, end dans day.” They repeat this call and response and then sing in unison:

We are the Indians, Indians, Indians of the nation

The wild, wild creation

We won’t bow down (We won’t bow down)

Down on the ground (On that dirty ground)

Oh how I love to hear him call my Indian Red3

The song is a declaration of existence, belonging, importance, and pride. In a few short lines of verse, black New Orleanians disappear behind a veil of what historian Angela Pulley Hudson calls “Indianness.”4 “You go into another place. It becomes emotionally overwhelming. Let the spirit go, and go where it pleases. Your warrior nature is awake. You’re in an alternate state,” said Big Chief Juan Pardo of the Golden Comanche.5 Beyond the suits they wear, the essential piece of being an Indian is projecting identity to other Indians. Who is the most Indian? Gazing upon the faces of the tribe, their immersion into their spiritual Indian identities is clearly evident as they sing together Mardi Gras morning. After “Indian Red,” another song from the Indian canon will be pulled out, like “Iko Iko,” “Sew, Sew, Sew,” “Shoo-Fly,” or “Let’s Go Get ’Em.”

As the Indian tribes begin their journeys across the city on Mardi Gras, traveling from uptown to downtown, or downtown to Algiers, they typically frequent gathering places in the old neighborhoods that have been used for generations. Shakespeare Park (now A. L. Davis Park), Second and Dryades streets, and under the Interstate 10 at Orleans Avenue downtown in the Treme neighborhood have endured as battlefields between those seeking to be the prettiest.

While on the path, the Spy Boys search out other Indians, serving as the eyes and ears of the Big Chief. Typically, a Spy Boy’s Indian suit is lightweight, with little in the way of a crown in comparison to the elaborate, often expansive ones worn by a Chief. This allows him to run ahead of the others and then report back. If the Spy Boy spots the approach of another tribe, he will signal the Flag Boy, who will alert the Chief and wait for directions. As the name implies, Flag Boys carry pennants attached to long staffs that are sometimes cut into the shapes of rifles or tomahawks. Their suits may be bulkier than that of a spy, but they too require the ability to move quickly. If, at the direction of the respective Big Chiefs, the tribes choose ...