![]()

1

Seed Saving

Past, Present, and Future

After fifty-plus years of collecting, growing, selling, and sharing seeds of heirloom beans, tomatoes, and a few other vegetables, I think I can generalize about the types of people who save seeds. I use the term traditional seed savers to refer to individuals who have never been separated from the land and who are following in family pathways.

In July 1988 the Rural Kentuckian (now Kentucky Living) published a well-written article by Judy Sizemore about my family’s farming operation that focused on our work with heirloom beans and tomatoes. Within five days we started getting letters and phone calls from people throughout Kentucky. Some wanted to get seeds for the greasy beans pictured in the article, while others wanted to send us some of their seeds. A man from Laurel County wanted to trade Nickell beans he had gotten years earlier in Elliott County for our greasy beans. Ruth Thomas sent me some of her Paterge (Partridge) Head beans from Clinton County. Her son Rudy had worked for me several summers in the Upward Bound program at Berea College.

And that was just the beginning. Within six months we had received letters from eighty-six people asking about beans, wanting to trade beans, and sharing bits and pieces of historical information. A few wrote about tomatoes, but most wanted to talk about beans. Some even lectured me a little. Others contacted us by phone or paid personal visits to our farm. And all this happened in the days before the Internet!

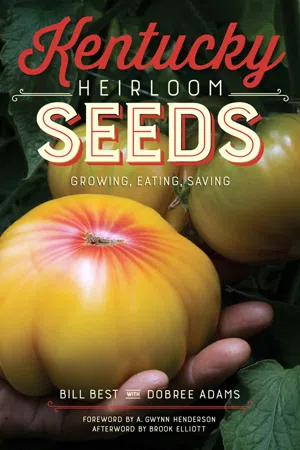

Tomatoes ready for eating! The Willard Wynn Yellow German tomato, one of our heirloom favorites. (Dobree Adams)

Even more astounding: some of the letter writers lived outside Kentucky (they came from six different states). Most of them were native Kentuckians who had migrated elsewhere to find work but were still gardening and swapping seeds and growing information. A few letters came two years later, referring to the same article, and to this day I occasionally run across people who have held on to that article.

Traditional Seed Savers

Some old-time seed savers can’t read and write, but they are intellectually sharp and know the value of traditional forms of knowledge. One of them was my next-door neighbor for many years, who taught me a lot about saving and growing heirloom vegetables. These old-timers know that seed companies have been putting out inferior products, although they might not be able to figure out why. Many are high school dropouts who have gardened all their lives and remember the hard times of the Great Depression. They have maintained the survival skills they grew up with and have no intention of becoming dependent on the benevolence of large corporations and giant factory farms. Some of them are retired factory workers and miners who are now dealing with crippling disabilities or respiratory problems, but they garden as if their lives depended on it. Most like the feeling of having a certain degree of independence.

Others are better educated but want to maintain their survival skills outside the system, either because they want to be prepared for the worst economically or because they have a simple love of growing things. I often hear them say, “I just like to see things grow.” Some are college graduates with several degrees, but they never “got above their raising” and strive to keep in touch with the ways of their ancestors and maintain historic ties with the land. I never cease to be amazed at the sense of history of so many seed savers, regardless of the amount of formal education. Many talk about great-uncles or great-grandfathers who fought on one side or the other during the Civil War. Border-state Kentuckians fought on both sides—often brother against brother or father against son. Or they speak of great-great-aunts or great-great-grandmothers who were renowned seed savers and had particular varieties named after them.

The Lexington Farmers’ Market

The farmers’ market in Lexington is one of Kentucky’s oldest continuous farmers’ markets in modern times. We started it in 1973 and, despite numerous setbacks, it has grown larger almost every year since then. Like me, a few of the founders had farmed and gardened all their lives, but several were going “back to the land” and saw the new market as a way to enter farming quickly and maybe even make a quick buck. Demand was heavy the first summer, with most vendors selling out by midmorning.

Local newspapers gave the market good coverage, and it didn’t take long for displaced eastern Kentuckians to start coming in droves to buy beans, tomatoes, potatoes, onions, sweet corn, greens, cantaloupes, watermelons, and all the other fruits and vegetables they had left behind in their own gardens when they migrated to Lexington to find work. People from other countries living in Lexington quickly discovered the market, and okra was especially popular among them; they usually bought all the okra available during the first few minutes of the market’s opening. Many people native to the Bluegrass had never eaten okra, but a number of vendors started growing it the next year to meet the high demand, especially from foreigners and southerners.

I am now the sole member of the original group still selling at the market. I started out as the youngest founding member and am now the oldest grower. I began selling heirloom beans soon after the market opened, growing what many people call “real” beans because I allowed them to become “full” prior to picking. I was simply growing the beans I liked, and I found that many of the customers liked them too.

Mrs. Elizabeth Tompkins has been patronizing the Lexington Farmers’ Market for decades and is probably my oldest customer. She celebrated her 100th birthday in September 2015. Here she is holding one of my tomatoes and one of my books. She will probably be first in line to buy this book!

Most of the other vendors at the market were growing and selling, or buying and reselling, bush beans, primarily stringless modern varieties such as Blue Lake and Tenderette. They were charging about two-thirds the price I was asking for my beans, so a lot of customers, being thrifty, bought the cheaper varieties, even though they didn’t look like the beans they had known in the past. It was sort of like buying a Yugo automobile—cheap, but not of very good quality.

I soon noticed that many customers would come by my stand and purchase a few of my beans to “flavor” the cheaper ones they had just bought. When I asked them to explain, they said they wanted to have some shelled beans to go with the others, which were just hulls. When my beans were cooked, the beans inside the hulls broke free, giving customers at least a hint of the beans they had grown themselves before moving to Lexington, where they often didn’t have enough space to plant a garden.

Once it was apparent that the farmers’ market was going to become a fixture, people from eastern Kentucky and from the mountain regions of other Appalachian states, where gardening was still practiced on a large scale, began to bring their family bean seeds to the market. They would give them to me, Ott McMaine, and a few others who were willing to grow them. And soon after that, customers started putting in orders for canning beans before the selling season began, a practice that continues to this day, more than forty years later. Several other growers got the hint and began growing the older types of string beans—beans that are now called heirlooms.

In the meantime, sellers of commercial beans were charging higher prices for machine-picked beans, which made heirloom beans even more attractive. There were no longer any cheap beans at the market, so there was no reason for customers who favored the heirlooms to mix them with commercial beans.

Concurrent with this renewed interest in “old-fashioned” or heirloom beans, heirloom tomatoes were also making a comeback. When the seed companies started selling mostly hard commercial-type tomatoes to gardeners, a slow rebellion started to emerge against tough and tasteless tomatoes, much akin to the rebellion against tough beans. Small specialty seed companies started to offer heirloom tomato seeds, and farmers’ market growers began to grow and sell the older varieties of tomatoes and save their seeds.

Growing early tomatoes in the high tunnel. (Dobree Adams)

Farmers’ market customers, some of whom also ate regularly at restaurants, suggested to restaurant owners and chefs that they look into buying heirloom tomatoes for their recipes, and the demand for heirloom tomatoes took another big leap. Restaurant owners, who had previously bought only hybrid, commercial-type tomatoes from large food distributors, suddenly started buying only heirloom tomatoes from farmers’ markets because of their freshness and superior flavor and texture. They featured heirloom tomato dishes, sometimes listing the names of the heirloom tomatoes, as well as the growers, on their menus.

As a rebellion against “fast food,” an international movement started in Italy in 1986. Called “Slow Food,” this movement brought additional attention to older types of fruits and vegetables and other food products, and it encouraged people to think a little more about the foods they were eating, how they were prepared, and what modern foods were doing to their bodies.

Several widely publicized food recalls in the 1990s convinced an already nervous public that they should pay attention to the sources of their food as well as its nutrient content. E. coli, listeria, salmonella, botulinum, and other germs suddenly became of interest to ordinary people, not just to microbiologists.

A new word entered the language: locavore referred to an individual who ate locally grown foods. At the same time, a “Buy Local” movement was occurring in many places, sometimes promoted by state agriculture departments, to encourage more interest in buying foods grown locally and in season. With the environmental movement pushing the idea of lessening one’s carbon footprint, buying local seemed to be an idea whose time had come. All this tended to make heirloom fruits and vegetables grown by local producers more attractive and offered a logical way to improve one’s health and to be more environmentally responsible, not to mention supporting the local economy and helping small farmers diversify and survive.

Keepers of the Seeds

When I first met Gwynn Henderson, she was giving a presentation that included a big-screen photo of bean seeds found in Kentucky that were several hundred years old. I was astounded because they looked so much like the beans I knew, and I am still intrigued by those ancient beans. As Gwynn reveals in the foreword, by the time Europeans began settling in the southern Appalachians, Native Americans had already established their seed-saving traditions.

The earliest evidence I have is from a college friend whose paternal ancestor arrived in the New World at the time of the American Revolution. Drafted to fight on the losing side, after the war he was given the choice of going back to Scotland or moving into the mountains of what would become western North Carolina. He chose the mountains, and soon thereafter he married an Indian woman. One of her contributions to the marriage was some greasy bean seeds. These beans are still part of the family’s seed collection some 240 years later. Of necessity, settlers saved seeds, traded with one another and with the Indians, and were heavily dependent on beans as a vital part of their diets.

The Cherokee Trail of Tears bean, a well-known heirloom of the southern Appalachians, is said to have been taken by the Cherokees on their forced march to Oklahoma. It has a beautiful fuchsia or maroon color.

Harriette Arnow, in her splendid and well-researched book Seedtime on the Cumberland, spends a lot of time discussing gardening and dietary habits. Beans are mentioned on fifteen pages, but tomatoes do not even make the index. Tomatoes were not common in early Kentucky, but they came in later with a vengeance. Arnow’s book talks about growing beans, preparing them for the table, and preserving them to be eaten during the months when gardens were not producing.

Almost every extended family in Kentucky, especially those from the eastern and south-central parts of the state, has one or more members who are growers of traditional beans and keepers of the family bean lore. Family reunions feature many bean dishes prepared in all the traditional ways—fresh green beans, fresh shelly beans, shuck beans, dry beans, pickled beans, and sulfured beans. And bean lovers usually sample all of them.

Some families still have bean stringings at canning time, when many bushels of beans have to be strung in a relatively short period in order to can many quarts of beans, sometimes numbering in the hundreds. Canned beans are often given as gifts to visiting relatives or to strangers who just happen by. Several gardeners I have interviewed insisted that I take home one or more jars of beans from the previous (or earlier) summer. Properly canned beans can last for years when stored in a dark, cool place.

Seed Saving and Culture

Traditionally, extended families saved enough seeds to get them through another year. In addition, community leaders such as preachers and politicians contributed to the dispersal of seeds to people outside the extended family. Preachers were often invited to eat with a family in the congregation after church, and they simply passed on the gift of beans received the previous Sunday to the next provider of dinner. Many of these bean varieties came to be called “Preacher Beans.” There are also numerous stories of politicians carrying bean seeds with them when visiting potential voters; they traded seeds with the voter and then moved on to the next house down the road, completing the cycle once again. I don’t know of any varieties called “Politician Beans,” but the stories persist. Preachers were typically held in higher regard than politicians.

I witnessed such seed trading as a child. My mother carried on seed-swapping rituals right up to the end of her life (she died a month short of her eighty-third birthday). We always had good beans to eat, and pots of beans were almost always on the cookstove, ready to be warmed up by adding a few sticks of wood to the fire. The beans never got completely cold and became better each day as the cured pork seasoning permeated the remaining beans.

I remember picking beans with my mother when I was just a few years old. I was captivated by the colors of the Hill family bean and by the bright green of the packsaddle stinging worm (often found feeding on the underside of corn leaves during silking), which my mother taught me to avoid at all costs. About ten or twelve years ago my cousin Clarine Green Best sent me some of those Hill family beans with this note:

These are the beans that we found in Ben’s mother’s can house in an open half-gallon jar after she had been gone for 15 or 20 years. We planted them and they came up. She had told us they had been in her family since she was a small child and that she used to carry them in a little apron and drop seeds for her mother who would plant them in the cornfield. In the fall they would pick bushels of these to pickle and to dry. When dry, they threshed them out on a large tarp and used as dry beans.

It would have taken a lot to make a mess since the Hills had 12 children. Ben’s mother, Cecile, would sit on her porch and fix these. She would shell out the ones that had gone to seed. She always threw away the black ones. Ronnie Hawkins remembers she used to let them have the black ones to play with. They would take bean hulls and make fences and pretend the shell...